Archive for Phonetics and phonology

What 'IPA' means now…

I have mixed feelings about the International Phonetic Alphabet. It's good to have standard symbols for representing phonological categories across languages and varieties. You need to know the IPA in order to understand books and papers on many speech-related subjects, as well as for practical things like learning to sing the words of songs in languages you don't know. And the IPA is certainly better than the various clunky alternatives for (symbolic) dictionary pronunciation fields. So I teach it in intro courses.

Read the rest of this entry »

Fusion phonology and morphology in Sinitic

Over the years, we have encountered on Language Log many instances of the fusion of Sinitic syllables into more compact units than the original expressions they derived from. A typical example is the contraction béng 甭 ("never mind; don't; needn't; do not have to") from bùyòng 不用.

Cf. zán 咱 ("we")

Fusion of 自家 (MC d͡ziɪH kˠa, “self”) [Song] > Modern Mandarin zá (Lü, 1984). Fusion with 們/们 (men) produces the form with a nasal coda [Yuan], e.g. Modern Mandarin zán (Norman, 1988).

(source)

Often such contractions and fusions in speech do not get reflected in the writing system as in the above two examples. For instance the Beijing street name Dà Zhàlán 大柵欄 = Pekingese "Dashlar" and bùlājí 不拉及, the transcription of Russian платье ("dress") is pronounced in Northeastern Mandarin as "blaji" (note the "bl-" consonant cluster, which is "illegal" in Mandarin).

Read the rest of this entry »

Wind head

ये चाचा ‘Lallantop’ है।

चाचा ने सर पर सोलर प्लेट लगाया है और उससे पंखा जोड़ को कडी धूप में मस्त ठंडी हवा का आनंद ले रहे है। pic.twitter.com/uJe3AZVt7C

— Shubhankar Mishra (@shubhankrmishra) September 20, 2022

Read the rest of this entry »

Disappearing readings of Sinoglyphs: focus on Bo (–> Bai) Juyi / Haku Rakuten

When I learned Mandarin half a century ago, it was a matter of faith, rectitude, and integrity that one should pronounce 說服 ("persuade") as shuìfú, not shuōfú, because when 說 is used with the meaning "convince; persuade", its pronunciation should be shuì, not shuō, which means "say; speak; explain", the more usual reading. Now, however, in the PRC, according to my students from there, the pronunciation shuì basically no longer exists, not even when the character 說 is intended to mean "convince; persuade", and not even in many dictionaries.

說 can also be pronounced yuè, in which case it means "happy; delighted", and is the equivalent of 悦 (and compare my remarks on the equivalent meaning / reading of 樂 below).

In addition, 說 can also be pronounced tuō and means the same thing as 脱 ("to free; relieve").

Read the rest of this entry »

Indirect archeological evidence for the spread and exchange of languages in medieval Asia

The title of this article about the Belitung shipwreck (ca. 830 AD) is somewhat misleading (e.g., there is no direct evidence of Malayalam being spoken by any of the protagonists, but it is broadly informative, richly illustrated, and well presented.

"Mongols speaking Malayalam – What a sunken ship says about South India & China’s medieval ties

The silent ceramic objects that survive from medieval Indian Ocean trade carry incredible stories of a time when South Asia had the upper hand over China."

Anirudh Kanisetti

The Print (8 September, 2022)

It's intriguing, at least to me, that the author identifies himself as a "public historian". He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India.

Read the rest of this entry »

Against physics

Or rather: Against the simplistic interpretation of physics-based abstractions as equal to more complex properties of the physical universe. And narrowing the focus further, it's a big mistake to analyze signals in terms of such abstractions, while pretending that we're analyzing the processes creating those signals, or our perceptions of those signals and processes. This happens in many ways in many disciplines, but it's especially problematic in speech research.

The subject of today's post is one particular example, namely the use of "Harmonic to Noise Ratio" (HNR) as a measure of hoarseness and such-like aspects of voice quality. Very similar issues arise with all other acoustic measures of speech signals.

I'm not opposed to the use of such measures. I use them myself in research all the time. But there can be serious problems, and it's easy for things to go badly off the rails. For example, HNR can be strongly affected by background noise, room acoustics, microphone frequency response, microphone placement, and so on. This might just add noise to your data. But if different subject groups are recorded in different places or different ways, you might get serious artefacts.

Read the rest of this entry »

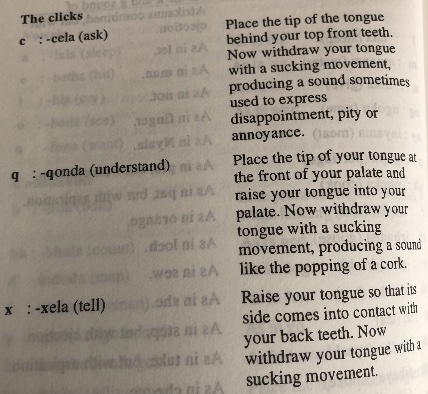

Xhosa clicks

[This is a guest post by Don Keyser, retired Foreign Service Officer, in response to "Complex vowels" (8/11/22).]

The mouseover title to the xkcd cartoon in the "Complex vowels" post: "Pronouncing [ṡṡċċḣḣẇẇȧȧ] is easy; you just say it like the 'x' in 'fire'."

This one took me on a ramble down memory lane. I spent the first three months of 1998 leading an inspection of our South African posts — South Africa (Embassy Pretoria, Consulates in Johannesburg, Durban and Capetown); Swaziland; and Lesotho. Majority government — i.e., black-ruled, under President Mandela — had come to South Africa. TV programming featured white hosts speaking Zulu or Xhosa, black hosts speaking English and Afrikaans. In the spirit of the new era. Multilingual signage was seen in the major cities. And so I ventured into a local book store to acquire guides to speaking isiZulu and isiXhosa.

Xhosa is a tonal language (high and low, basically) best known for its "click consonants" — a language introduced to Americans by Miriam Makeba in her "Click Song (Qongqothwane)."

So … perusing the short tourist-type guide to Xhosa* that I bought, I found this delightful "explanation":

Read the rest of this entry »

"Sound" at the center, "horn" at the periphery: the shawm and its eastern cousins, part 2

For a good example of how music and musical instruments, together with the words to designate them, could travel long distances in antiquity, we have already taken a look at the case of the shawm: "The shawm and its eastern cousins" (11/16/15). Since writing that post nearly seven years ago, a few more interesting facts about the shawm family have come to light, so it's time to revisit this raucous instrument.

I first encountered this melodic noisemaker in the guise of the Chinese suǒnà 嗩吶. Inasmuch as the Sinographic form has two mouth radicals, that could be to emphasize that it has to do with making sounds, which is definitely true, but that might also indicate that it is a transcription of a foreign word, which is certainly the case. The latter is underscored by the fact that it has the variant orthographic form with a metal radical on the first character: 鎖吶.

So where did the suona come from, and how did it get to China? By investigating suona's linguistic ancestry, we can get a pretty good idea of the route by which it came to the Middle Kingdom.

Read the rest of this entry »

Does "splooting" have an etymology?

In the summer of 1990, I spent a memorable five weeks at the outstanding summer institute on Indo-European linguistics and archeology held by DOALL (at least that's what we jokingly called it — the Department of Oriental and African Languages and Literatures) of the University of Texas (Austin). The temperature was 106º or above for a whole month. Indomitable / stubborn man that I am, I still insisted on going out for my daily runs.

As I was jogging along, I would come upon squirrels doing something that stopped me in my tracks, namely, they were splayed out prostrate on the ground, their limbs spread-eagle in front and behind them. Immobile, they would look at me pathetically, and I would sympathize with them. Remember, they have thick fur that can keep them warm in the dead of winter.

I assumed that these poor squirrels were lying with their belly flat on the ground to absorb whatever coolness was there (conversely put, to dissipate their body heat). At least that made some sort of sense to me. I had no idea what to call that peculiar, prone posture. Now I do.

Read the rest of this entry »