First novels

« previous post | next post »

I traditionally start my phonetics courses with an "over-under bet", about how much randomly-selected audio we need to listen to (and look at), before we find a systematic, interesting, and essentially unstudied phenomenon. In the case of English, I generally offer 20 seconds as the threshold value — for less well-studied languages like French or Chinese, the threshold might be 10 seconds. For understudied languages, 3 seconds.

This came up a few weeks ago in my corpus phonetics course, and so we took a look at the most recent Fresh Air podcast at that point: "With a nod to 'Lolita,' 'Vladímír' makes a sly statement about sex and power", 2/22/2022.

Here's the first bit of the show (a little less than 12 seconds):

This is Fresh Air.

Our book critic Maureen Corrigan says

Julia May Jonas's new first novel,

called Vladímír,

should spark a lot of heated discussions

on today's campuses.

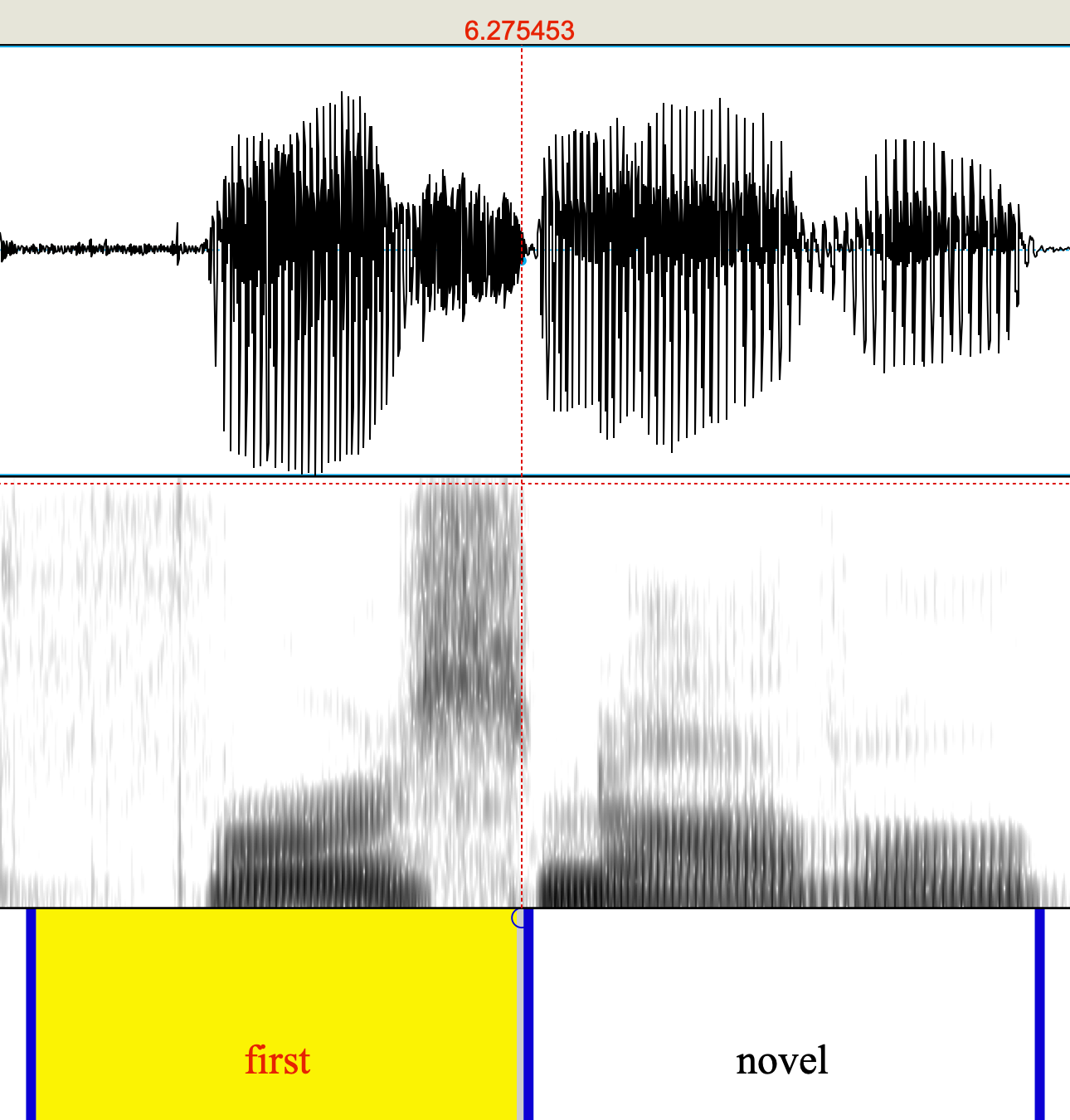

And the first interesting-and-unstudied phenomenon turns up after about 6.2 seconds:

What's interesting about it?

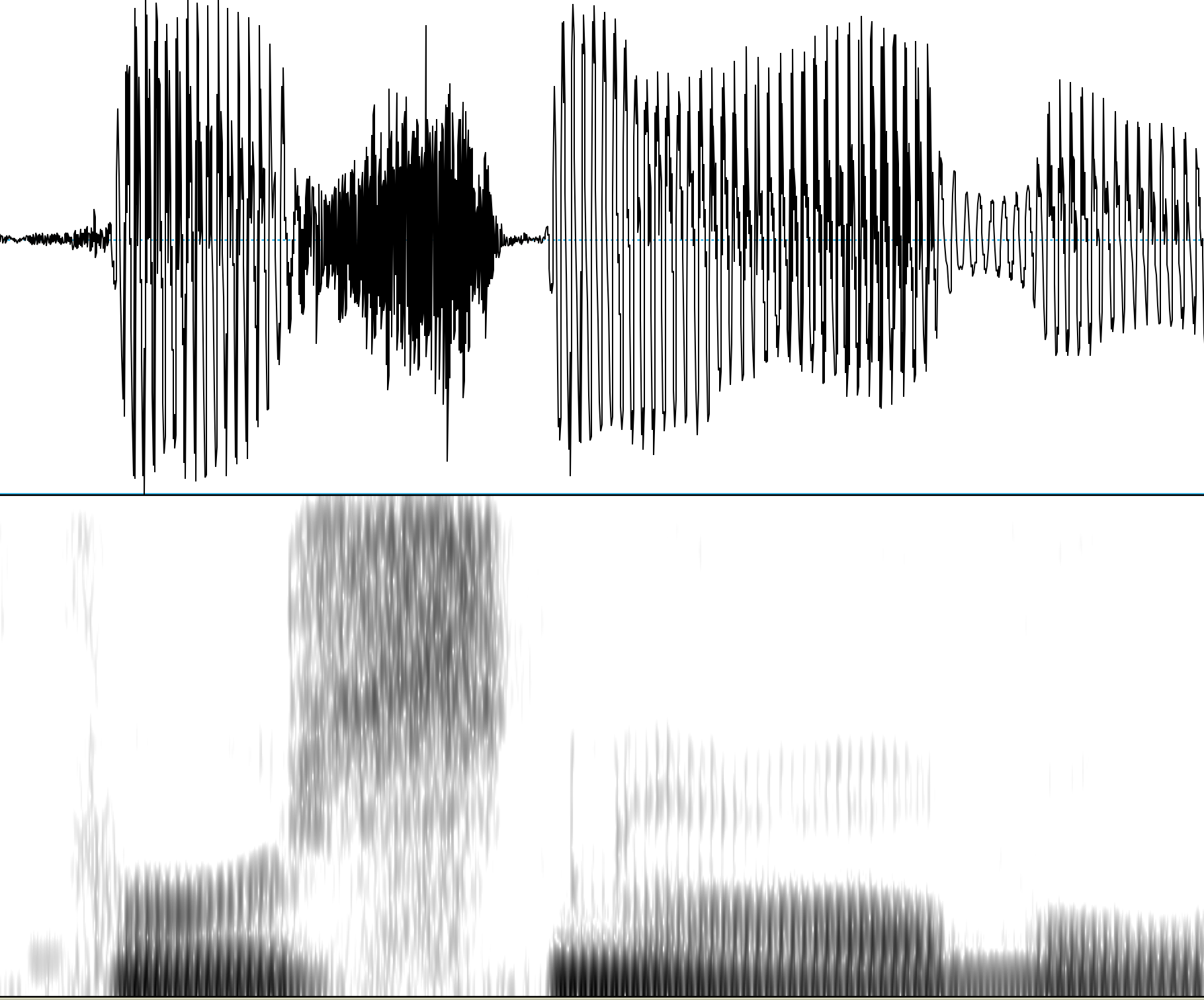

Well, basically there's no sign of the /t/ in "first". The tiny (less than 10 msec.) low-amplitude region between the [s] and the [n] is typical of fricative-nasal transitions, as in "this novel" or "Miss Nancy". Listen to the /s/ of "first" and the first syllable of "novel", which just sounds like "sna":

Informed readers may object that this is just (an example of) the well-known phenomenon of "t/d deletion". We saw another case of vanishing /t/ in "On beyond the (International Phonetic) Alphabet", 4/19/2018. But as far as I know, no one has looked at what happens to /t/ in this particular context:

Vst#nV = VOWEL+/s/+/t/+WORDBOUNDARY+/n/+VOWEL

As in the "-ists" case discussed in the cited LLOG post, we're led to wonder whether this case of /t/ allophony (contextual variation in pronunciation) should be handled symbolically — i.e. viewed as deletion of a discrete segment or feature in some mental version of a phonological representation — or rather as the end state of a phonetic process of lenition (= weakening), or perhaps the result of phonetic changes in the phase relations among the articulators involved.

There are some relevant discussions in the literature: Jeffrey Kallen, "Internal and external factors in phonological convergence: the case of English/t/lenition", 2005; Lisa Davidson, "Characteristics of stop releases in American English spontaneous speech", 2011; Patrick Honeybone, "Lenition in English", 2012, etc. And I addressed the general problem in "Towards progress in theories of language sound structure", 2018, though without discussing the t/d lenition/deletion case.

All the same, this particular case counts as empirically unstudied, as far as I know. So for this morning's Breakfast Experiment™, I looked at 100 randomly-selected examples of the word sequence "first novel". As in some previous posts and some lecture notes from last spring's Syntax and Prosody seminar I took them Shuang Li's INTERVIEW: NPR Media Dialog Transcripts dataset, which contains 3,199,859 transcribed turns from 105,817 NPR podcasts, comprising more than 10,648 hours.

I don't have time now for a full discussion of the results, but here's a quick summary of the highlights.

- There were just two (of 100) cases where the /t/ was released — I excluded those from further analysis.

- In all the others, I measured the durations of

(a) the /ɚ/ vowel in "first"

(b) the /s/ frication in "first"

(c) the /t/ closure if any (duration 0 if absent)

(d) the /n/ nasal murmur from "novel"

Although the underlying articulatory gestures are heavily overlapped, as always, in these cases the acoustic physics yields relatively sharp transitions between phonetic regions, so durations measures are well defined. - In 21 of the examples, the /t/ closure duration was 0.

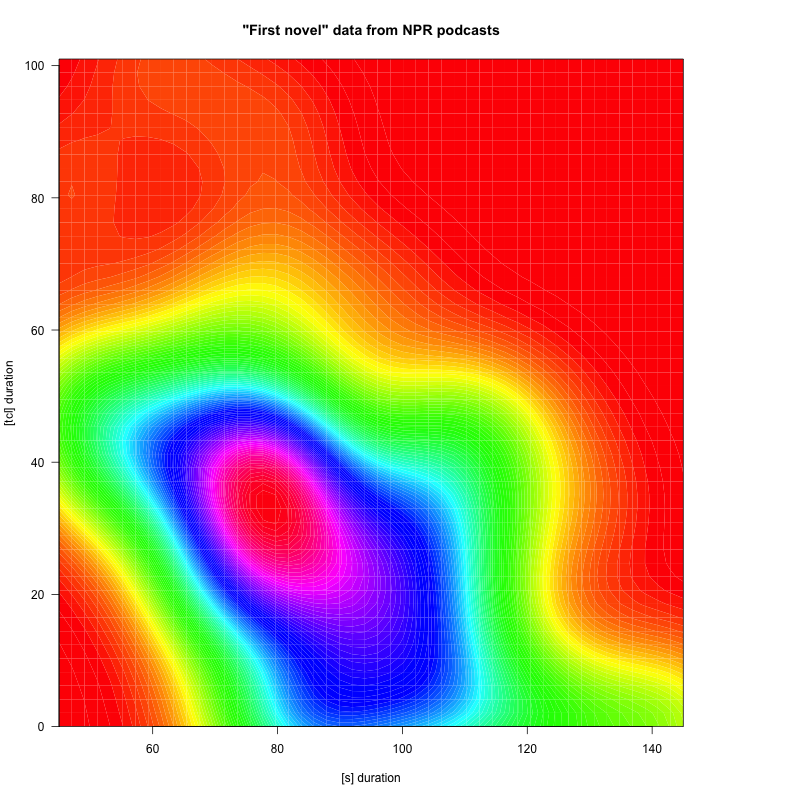

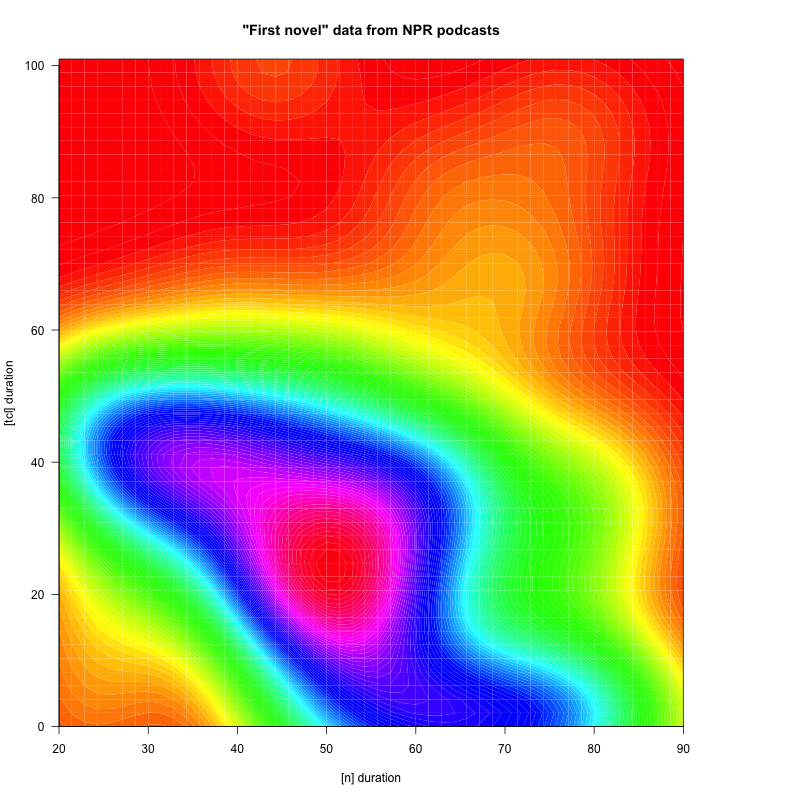

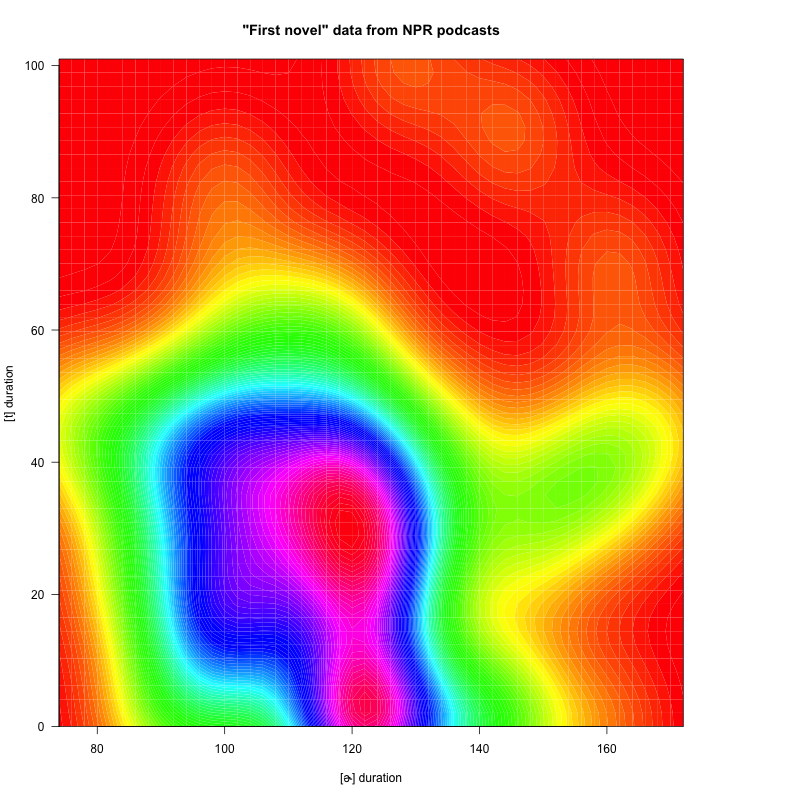

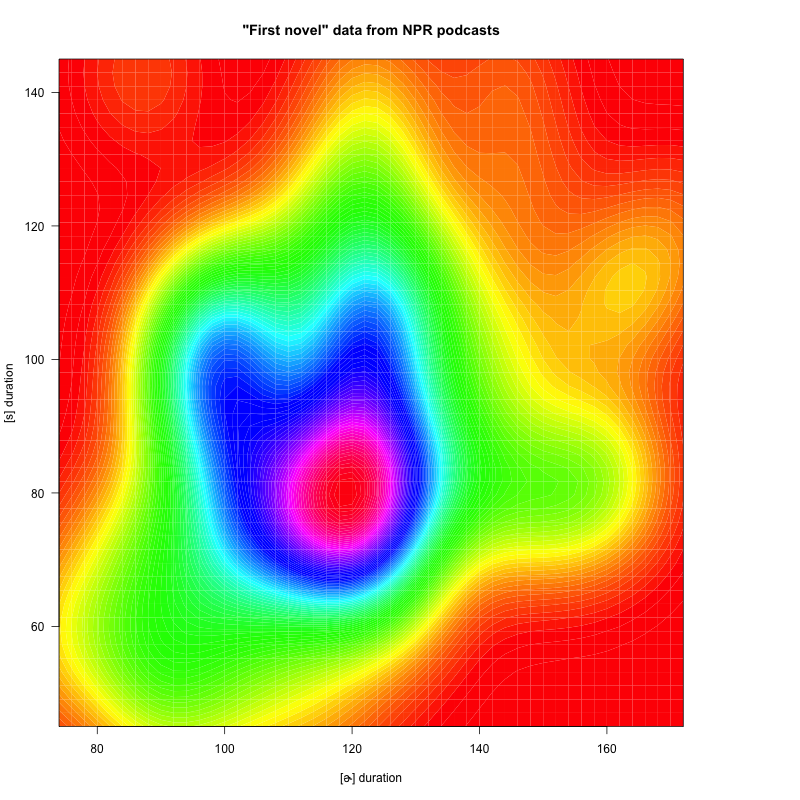

- Some duration correlations:

/s/,/t/: -0.531

/n/,/t/: -0.284

/ɚ/,/t/: -0.022

/ɚ/,/s/: 0.323

Here are some 2-d kernel density plots:

There's little evidence here for the kind of crisp bimodal distribution that we would expect if the underlying phenomenon was qualitative segment deletion. Rather, we see multivariate correlations of the type that we expect given gestural phasing among the tongue, the larynx, and the velum, along with some tricky physics creating the "quantal effects" that give us relatively sharp acoustic transitions between [ɚ] and [s], [s] and [tcl] (= "t closure"), [tcl] and [n].

There are obviously many uncontrolled covariates here, among them the stress/focus pattern (is the speaker contrasting the "FIRST novel" as opposed to later novels?), the speaker ID (because a handful of different hosts are among the speakers), the novelty of the phrase in context, and so on. We should look at more word sequences (e.g. "lost money", "just not", "first name", "less money", …), and more diverse data sources.

But at least this is a start, and it's all I have time for this morning.

Benjamin Geer said,

March 13, 2022 @ 1:43 pm

Is there an explanation of why this varies so much between languages? I remember when I learned the German word Impfpflicht [ˈɪmp͡fˌp͡flɪçt] and I asked Germans, "Do you really pronounce all those consonants, or do you drop some of them?" And they said, "We really pronounce all of them." I was pretty sure that if it was an English word, at least half of them would be dropped.

[(myl) It wouldn't be a shock to learn that your German consultants were suffering from the "phoneme restoration effect".

But still, there's a wide range of tolerance among languages (and language varieties) for complex syllable structures, and consonant sequences in particular. Some languages want syllables to be strictly CV, other allow only nasals in syllable-final position, and so on to Berber and Salish languages. And it's common to see a historical cycle — Portuguese went through the general Romance trend of simplifying Latin syllables, but the Portuguese pendulum has swung quite far back in the other direction, with vowel reduction and lenition-unto-deletion creating some spectacular consonant sequences, especially in Lisbon, where this has gone so far that Brazilian acquaintances tell me they can't understand the Europeans any more. Some relatively formal examples are here.]

Jerry Packard said,

March 13, 2022 @ 2:29 pm

Thanks for the post! I tend toward the gestural-multivariate model because it doesn't seem reasonable to assume that speakers are 'deleting a segment t' to get the observed output, rather than simply tweaking gestural features to glide into a following segment as ‘the end state of a phonetic process of lenition.’

If it’s an instance of sound change in progress one could wonder whether the multivariate tweaking of gestural features occurs in all environments in which conditions are met (Neogrammarian hypothesis) or in word-by-word fashion across the lexicon (lexical diffusion).

ulr said,

March 13, 2022 @ 3:23 pm

@Benjamin Geer : those Germans you asked either lied to you or they are delusional about their own pronunciation – in a language where spelling and pronunciation are closer than in English people tend to be blind to the cases where they deviate. In normal situations it's almost always [ʹʔɪmɸlɪçt], everything else would sound ridiculously pedantic, in fact it's the kind of pronunciation you expect from foreigners. Even [pf] instead of [ɸ] (which is often simpllified to [f]) tends to sound pedantic.

JPL said,

March 13, 2022 @ 3:55 pm

Did muscular enunciator Maureen Corrigan by chance also utter the phrase in question?

[(myl) No. In this review, she uses the an elevated version of the phrase:

The guilty pleasures of Vladímír, a virtuoso debut novel by Julia May Jonas, begin with its cover: a close up from the neck down of man's very nice open-shirted chest and hands resting on his clothed crotch.

But we can find examples of the phrase in other episodes, for example this passage from "How 'Gatsby' Went From A Moldering Flop To A Great American Novel", 9/8/2014:

Here's the "first novel" bit:

[ɚ] 115 msec., [s] 126 msec., [tcl] 27 msec, [n] 43 msec.

]

Peter Grubtal said,

March 14, 2022 @ 2:49 am

Is the "phoneme restoration effect" distinct from "spelling pronunciation"?

It's years since I read that to pronounce the "t" in "often" is just the latter. The "t" only appeared in the written word because in the early days of printing typesetters made a false analogy with "oft".

Wouldn't the Portuguese phenomenon haven't something to do with that?

It's possible that we all correct ourselves sometimes nowadays, consciously or unconsciously, based on written forms.

[(myl) The phoneme restoration effect and spelling pronunciation are both real things, but they're different. "Phoneme restoration" reflects the role of expectations ("top-down" processing; "language models"; etc.) in perception, and it applies even for speakers of languages with no writing system, or for people who haven't learned to read. "Spelling pronunciation" reflects the fact that much of literate people's vocabulary comes from reading, and since they've never heard the words in question, they internalize a pronunciation based on their interpretation of the spelling — which in English is a very unreliable guide. ]

J.W. Brewer said,

March 14, 2022 @ 11:20 am

About a dozen years ago there was a post and thread here about the phenomenon of AmEng speakers who pronounce "across" as "acrosst," of whom I am one, at least sometimes but not always. I've never put in the effort to try to identify any meaningful patterns in my own ideolect as to when the /t/ gets pronounced and when it doesn't, but I suppose it would be interesting if it were just an example of a broader phenomenon of deleting word-final /t/ after /s/ (which I guess would mean I have the t-full version stored in my mental lexicon as the canonical form but it doesn't always get articulated that way), rather than e.g. a code-switching thing where I am more likely to suppress the deprecated dialect-and/or-regional pronunciation when I am self-consciously in formal-register mode.

One data-collection difficulty is that I feel like I notice the "acrosst" form more when it's sentence-final (e.g. this morning I said "come on acrosst!" to one of my kids who was dawdling in the middle of a crosswalk while I was walking him to school), so there was no immediately-following word to create a prosodic/phonological context in which t-deletion might have been propitious.

Bloix said,

March 14, 2022 @ 12:13 pm

Peter Grubtal –

The OED tells us that often is an extension of oft or ofte, and that Chaucer used both. The OED says that he used ofte before consonants and often before vowels and h, but I looked at the Canterbury Tales and Chaucer's usage seems more linked to meter.

Examples from the Prologue of the Canterbury Tales:

In Lettow hadde he reysed, and in Ruce,

No Cristen man so ofte of his degree.

[No christened man of his rank had raided in Latvia and Russia as often as he.]

A SERGEANT OF THE LAWE, war and wys,

That often hadde been at the Parvys,

[A lawyer, prudent and wise, who often had been at St Paul's Porch]

The OED gives examples from Chaucer and others, many of whom wrote before Gutenberg. There's no non-t spelling, and typesetters didn't insert the t erroneously in often – or in soften, hasten, or fasten, for that matter.

Peter Grubtal said,

March 14, 2022 @ 1:22 pm

Bloix –

ok, it seems I was wrong to blame the printers. But I remembered where I first came across the anecdote and found – mirabile dictu – the book was still on my shelves: Our Language – Simeon Potter (price 4 shillings). In fact Potter doesn't blame the printers either, so I remembered that wrong. He does say though that Queen Elizabeth (I!) wrote it "offen".

Julian said,

March 14, 2022 @ 4:49 pm

Asking a German how they pronounce 'impfpflicht' sounds a bit like asking an English speaker how many syllables there are in 'library' or how many R's there are in 'February' or how many consonants there are in 'strength'. I wouldn't count on getting an accurate an answer.

Michael Watts said,

March 14, 2022 @ 5:43 pm

But that doesn't tell you anything about whether the /t/ was there originally. Queen Elizabeth is from the 16th century. The word had been around for several hundred years by her time. You might just as well argue that the "t" in often is spurious because Gilbert and Sullivan indicate that it wasn't pronounced.

I think the bigger problem with this particular example is that people will use different senses of "consonant" when answering. "Strength" may be physically more difficult than average, but it gets pronounced the way you'd expect from the spelling, or from the phoneme sequence.

I still treasure the example I found in a discussion of "Are some languages spoken faster than other languages?", which concluded that it's possible in certain languages to create sentences that have to be spoken slowly on a per-syllable basis — such as "Smith's strength crunched six sleek ships" — but that this doesn't occur much in ordinary speech.

Jerry Packard said,

March 14, 2022 @ 10:26 pm

There is evidence that some languages are actually spoken faster than other languages. In a fairly rigorous study using a large data sample, Pellegrino et al. found the following ranking of languages by syllables spoken per second (Pellegrino, F. , Coupé, C. and Marsico, E. (2011). Across-Language Perspective on Speech Information Rate. _Language 87:3_. Pp. 539-558):

Japanese 7.84

Spanish 7.82

French 7.18

Italian 6.99

English 6.19

German 5.99

Mandarin 5.18

[(myl) An earlier version of that work was discussed here back in 2008: "Speech rate and per-syllable information across languages".

The 2011 paper (Christopher Coupé et al., "Different languages, similar encoding efficiency: Comparable information rates across the human communicative niche") used a method that may be subject to some problems:

We collected recordings of 170 native adult speakers of the aforementioned 17 languages, each reading at their normal rate a standardized set of 15 semantically similar texts across the languages.

The "Supplementary Material" offer the data tables underlying their statistical analysis. But they don't provide the "semantically similar" texts, so we can't rule out effects of textual differences (syntactic or rhetorical complexity, for example). The recordings were (apparently) done in Paris, which means that the speakers for different languages might have varied in relevant features such as education level, speaking style, psychological reaction to the experimental setting, etc. For example, it's possible that several of the "Chinese" subjects were not in fact native speakers of Putonghua. And the "syllables" were tallied by an automatic syllable-detection method, which might have had different error rates for different languages — they don't provide the audio recordings, so we can't check.

It would be interesting to compare results for other sources of data, for example the various CallHome conversational datasets (available for Mandarin, Spanish, Japanese, German, American English, and Egyptian Arabic), or broadcast news in various languages from similar sources (such as VOA or BBC), or a selection of audiobooks.

Definitely the subject of a future Breakfast Experiment™! ]

Philip Taylor said,

March 15, 2022 @ 4:45 am

« Queen Elizabeth (I!) wrote it "offen" » — HM QE I was possibly not as attentive at her lessons as she might have been: her Greek tutor, Roger Ascham, famously wrote of her that she spoke the language 'frequently, willingly and moderately well'.

Andreas Johansson said,

March 15, 2022 @ 8:20 am

@Jerry Packard:

Is there a principled reason for measuring speaking speed by syllables per second rather than, say, phones per second? Clearly the average English syllable is going to have more phonetic content than the average Japanese one.

J.W. Brewer said,

March 15, 2022 @ 11:06 am

@Andreas Johansson: The takeaway of that Pellegrino et al. paper is supposedly that there's a negative correlation between "average information density" and speech rate. So the more information per syllable (English > Japanese, for example), the slower the tempo as a very general matter. Note that Mandarin (not very many phones per syllable but then there's an overlay of phonemic tone which is itself information-bearing) is the slowest tempo on the list. I do think that if you were trying to assess the tempo of someone's speech in a beats-per-minute sense you would generally treat syllables (or conceivably morae) as the "beats," not least because you don't really hear the individual phones as forming that sort of rhythmic pattern.

On the other hand, within a farflung language community like that of English speakers, speakers from certain regions are stereotyped as unusually fast-talking (compared to some basic default norm as to speed) and those from other regions as unusually slow-talking. Assuming any empirical grounding for those stereotypes at all, that's not about some sort of tradeoff between speed and information density, which will presumably be constant on a per-syllable basis across regions in the same language.

Andreas Johansson said,

March 16, 2022 @ 2:00 am

Pragmatically, you might think the relevant measure of talking speed is the bit rate. How long does it take to convey the same information in different languages?

(This is going to depend on the subject matter, obviously. Talking about some technical subject in a language that simply doesn't have the vocabulary for it is going to be slow no matter how fast the language may "intrinsically" be.)

I guess this would imply that the speed of phatic speech is zero …

Jerry Packard said,

March 16, 2022 @ 6:16 pm

Thanks to myl for the explication and proposed extensions of the Coupé et al. 2011 paper.

Andreas Johansson's 'bit rate' might seem to be a viable method, but 'more time' is not = 'talking faster', it's just 'more time' = 'more speech'.

I think I agree with J.W. Brewer regarding the value of the syllable rather than 'phones', because however ill-defined, 'syllable' might be more easily measured and quantified. Phones would seem to be more difficult.

Andreas Johansson – your zero speed of phatic speech may be a useful quantum approach to the coding/decoding of speech information: zero speed = zero mass.

mollymooly said,

March 17, 2022 @ 1:38 pm

Vst#nV = VOWEL+/s/+t/+WORDBOUNDARY+VOWEL

should be

Vst#nV = VOWEL+/s/+t/+WORDBOUNDARY+/n/+VOWEL