Pronunciation evolution

« previous post | next post »

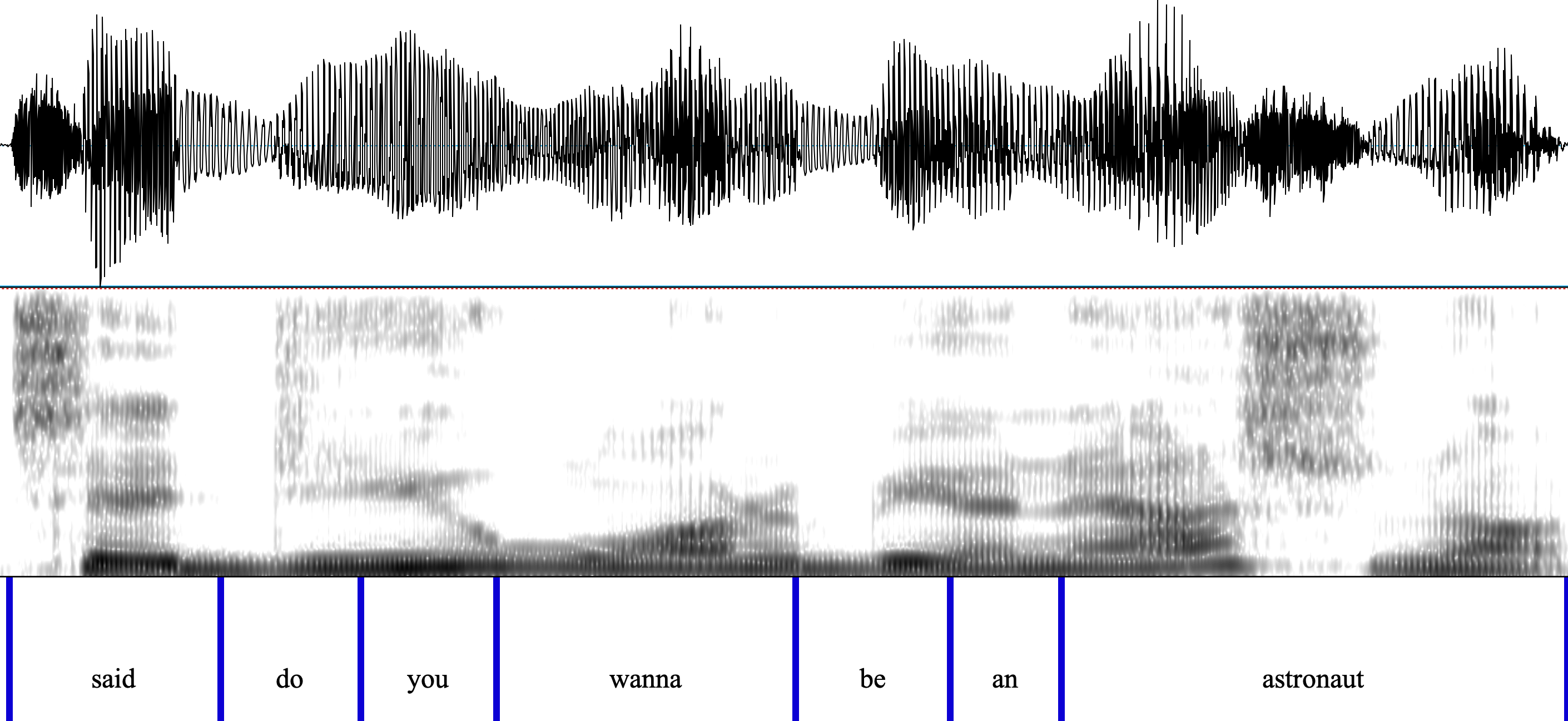

Listening to a StoryCorps conversation about the history of women in NASA's astronaut corps as Wally Funk experienced it, I noticed something (phonetically) striking in her first sentence:

Zeroing in a bit:

And a bit more:

You should be able to hear that she pronounces "astronaut" roughly as if it were the two-word sequence "ash naught". To help you, I've cut that last audio clip into two pieces at end of the fricative noise corresponding to the /s/ of "astronaut":

Was this a slip of the tongue, or something weird about Wally Funk's idiolect?

No.

Taking a look at a sample of 100 instances of "astronaut" in the previously-described NPR podcast corpus, I found several similar cases where the word has only two phonetic syllables, with the first ending with a fricative and the second starting with [n]. And in more than half of the cases, the unstressed medial syllable is not elided, but the /t/ vanishes completely, and the /r/ is retained only as spectral lowering at the end of the /s/. I don't have time this morning to lay those examples out and discuss them, but I'll put it on my to-blog list for tomorrow.

The point is, this sort of thing is ubiquitous. In every language, including English, there are common (and something extreme) variations in pronunciation caused by weakening, co-articulation, and phase changes in articulatory gestures. Most such variations have never been systematically studied — or in most cases even noted in passing — due to some combination of the phoneme restoration effect and the herd instincts of academics.

For well over a century, linguists and other scholars have described these variations as substitutions of one quasi-alphabetic symbol string for another — with the phonetic symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet now the standard.

Some acute observers have always recognized that this was a mistake, from a scientific point of view, even if no other description was really possible in the days before audio recording and instrumental analysis were possible. As applicable technology has improved and become more accessible, the mistake has become more obvious, since such "allophonic variation" is typically and obviously gradient: the different IPA symbols are labels for regions of a continuum, like labelling people as "tall" or "short".

There can be "quantal effects" due to the physiology and physics of the situation; and of course such variation eventually leads to changes in a language's underlying systems, through processes of social and psychological evolution that remain imperfectly understood. But the practice of treating (nearly all) pronunciation variation in categorical, symbolic terms has persisted, due to a combination of cultural conservatism and lack of relevant technical training.

We've discussed similar issues in previous posts, e.g. "On beyond the (International Phonetic) Alphabet", 4/19/2018, and "First novels", 2/13/2022). For a more general discussion of the history and the issues, see "Towards Progress in Theories of Language Sound Structure", in Shaping Phonology, Brentari & Lee, Eds., 2018; and "Corpus Phonetics", Annual Review of Linguistics 2019.

Philip Taylor said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:14 am

I don't hear "an ash naught" (/ən ˈæ nɔːt/), I hear "an ash not" (/ən ˈæ nɒt/).

Philip Taylor said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:15 am

Sorry, the /ʃ/s were accidentally omitted in the above.

Jim Mack said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:20 am

I don't know if it's this phenomenon or just lazy elision, but two examples you can hear almost any day in the news are "presn united states" (for "president of") and "so security"

Antonio L. Banderas said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:30 am

@Jim

What does "so security" refer to?

Bob Ladd said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:49 am

I think Jim Mack's examples are indeed the same phenomenon. Lots of people have occasion to talk frequently about the "president of the United States" or "social security", so the speeded up / reduced forms are fairly common. Fewer people have regular occasion to talk about astronauts, so not so many people have a speeded up or reduced version of "astronaut" in their regular speaking repertoire. But the only difference is how widespread the speeded up forms are, and probably a lot of people have a few idiosyncratic ones. I once worked with an ethnomusicologist whose pronunciation of "ethnomusicology" often seemed to involve only about four syllables.

Separately, of course, I agree with MYL about the futility of trying to capture this kind of stuff with IPA transcriptions.

Gregory Kusnick said,

April 15, 2022 @ 12:51 pm

I was going to remark on Bob Dole's truncated pronunciation of "presidency" but I see I have already done so in a previous thread.

Coby Lubliner said,

April 15, 2022 @ 2:36 pm

I did not hear the usual anglophone allophone (I love this combination of words) of /ʃ/, but rather the same -str- cluster that would have been there if the schwa (representing the o) had been articulated, something more like a Slavic sč.

[(myl) I think all those tongue gestures are there, but blended together and phased with the laryngeal gestures so as to produce a single complex fricative, rather than being spaced out in a nice neat segmental sequence of [s] [t] [th] [r]. And as you'll see when I present examples from the NPR Podcast corpus, this is totally normal for American speakers even in a relatively formal genre.]

Michael Watts said,

April 15, 2022 @ 5:03 pm

I have to disagree with the idea that the recording sounds like "ash naught".

To my ear, the /t/ has not disappeared. The recording very clearly says /æstʃ__nɑt/. I put some underscores in there, and what's happening where I have the underscores is not clear – I would accept a variety of descriptions, such as /ɚ/, /ɹ̩/, /ə/, or even zero, but it is clear that what follows /æs/ is definitely /tʃ/ and not /ʃ/.

(And this makes sense, since /t/ before /ɹ/ automatically becomes /tʃ/, whereas there is no mechanism by which /ʃ/ would appear.)

Julian said,

April 15, 2022 @ 5:09 pm

The element that you rendered as 'sh' is something that I hear as a more raised/back palatal fricative a bit like Chinese 'x' (apologies if I've got the terminology wrong)

Michael Watts said,

April 15, 2022 @ 6:02 pm

Blending may be going on, but I think sequencing is still present. If you could find toddlers who were unfamiliar with the word "astronaut", and played the recording for them, I bet interpretations such as "astronaut" and "as-ch-naut" would be far more common than e.g. "atch snot".

JPL said,

April 15, 2022 @ 6:36 pm

For some speakers of AmE (quite a few, actually, it seems: e.g., Michelle Obama is one), the pronunciation of the -str- cluster involves (please correct my terminology) palatalization of the sibilant to a fricative articulation, while others (probably the majority) retain the apical articulation for the sibilant. Does this speaker fall into the former group? I would doubt whether speakers in the latter group would pronounce the word 'astronaut' in a similar reduced way, but with the apical sibilant, and without the other articulations. It seems like for this speaker the fricative is considered sufficient as a stand-in for the entire cluster and it is conventionally understood as such; but that probably wouldn't work for the apical articulation. So why would that be? (Is the palatalization moving "backwards" (i.e., in anticipation) in the pronunciation of -str- clusters for the former group?)

David L said,

April 15, 2022 @ 8:20 pm

I agree with Michael Watts. What I hear in the 'str' part of astronaut as she pronounces it is a sound coming from the tongue pressing against the roof of the mouth and the upper teeth, whereas 'sh' is further back in the mouth. The 't' is not separately articulated but it has not disappeared entirely.

(It is possible that JPL is saying the same thing but I am not sufficiently familiar with the terminology).

Y said,

April 15, 2022 @ 11:34 pm

I hear this "spectral lowering", too. I think the [ʃ] moves back at its end, toward [ʃ̠], which approximates a bunched [ɹ̥].

Adrian Bailey said,

April 16, 2022 @ 4:26 am

Like some of the other commenters, I (believe I) can hear the t, so it's as(h)tr'naut. What struck me when I heard the audio clip was the extreme shortening of "[..] said" after "call;".

Chris Button said,

April 16, 2022 @ 5:11 am

I agree, although the IPA tie-bar along with a bunch of diacritics can help.

It also goes far beyond phonetics. A long time ago I posted something to that effect here:

https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=25730#comment-1513560

Once you start reconstructing historical phonology, the vowels tend to disappear—Proto Indo-European and Old Chinese being the classic examples to leave syllabic chunks (which are essentially the basic building blocks of language—problematic in themselves, but anything smaller than that is necessarily an abstraction). The supporting “real world” examples of Northwest Caucasian languages unfortunately tend to end up as a red herring. Sure, they’re (near) “vowelless” in terms of phonology, but they’re replete with vocalic—and doubtlessly allophonic—variation on the surface.

Just don’t get me started on the notion of Old Chinese rhymes…

Chris Button said,

April 16, 2022 @ 7:34 am

So the northwest Caucasian languages are not “anomalous”, but rather exactly as would be expected—as is the case for Old Chinese and PIE for that matter (once e/o is treated as schwa/a)

Now back to phonetics…

Viseguy said,

April 16, 2022 @ 10:24 pm

When I play the audio clips from top to bottom, I hear something like a "tr" between "ash" and "naught" until the last (divided) clip. But when I play the clips from bottom to top, starting with the one that divides "ash" and "naught" into two, I only hear "ash" and "naught" all the way through. Neither seems more, or less, real than the other. Clearly, an auditory illusion is in play, but which is real and which is the illusion?

Chas Belov said,

April 17, 2022 @ 2:03 am

In my family, at least my mother and me, we elided "might as well" to "mize well". Even when I say it just now, I feel the "t" in my mouth but it somehow doesn't make it out into the sound waves.

When I listened to that first sentence, I believe I similarly detected a hint of that "tr" that didn't quite make it out of the speaker's mouth into the ether.

Philip Taylor said,

April 17, 2022 @ 8:17 am

I can certainly imagine someone saying "mize well", Chas, but in my mind I hear a hint of a glottal stop in the middle of "mize", separating the phrase into 2.5 syllables (/maɪ-ʔ-zwel/).

Chas Belov said,

April 17, 2022 @ 1:39 pm

Philip, yes, I can get that, just did it. It felt unfamiliar in my mouth, so I'm guessing I didn't do that. And maybe I didn't even sub-vocalize the "t" back then, since I learned it from my mother as a little kid. But it's been years since I've said it (until now) so ¿who knows?

Chas Belov said,

April 17, 2022 @ 1:41 pm

That is to say, I may have learned "mize well" as a set phrase and didn't even think of it as "might as well" although I eventually figured out that this must have been what the actual phrase was.

Misha Schutt said,

April 17, 2022 @ 11:44 pm

My junior high English teacher once told us that he had learned “farveroo” as a single word and only later understood it as “if I were you.”

Philip Taylor said,

April 18, 2022 @ 1:53 am

For at least two years after starting school at the age of five, I was convinced that there was a verb "to truvallacy", whose meaning I failed to comprehend; all I knew was that it occurred in one line of a school hymn — "Who would truvallacy, let him come hither". I also thought that there was a word "roo-eye-inn", which occurred in one line of a school song — "A-roving, a-roving, since roving's been my roo-eye-inn". Going in the other direction (from spelling to imagined sound), I was convinced that "foliage" should be pronounced /fɔɪ-lɪdʒ/ and "lieutenant" /lɔɪ-tə-nənt/.

Michael Watts said,

April 18, 2022 @ 8:53 pm

Hm. As far as I know, I was always familiar with the standard pronunciation of the word (/lu.'tɛn.ənt/). That's not really relevant to imagining how it would be pronounced in the absence of that knowledge, but I'm having a hard time drawing an analogy to any other pronunciation of the same set of letters. -ieu isn't all that common, but there is an obvious analogue, lieu, which is also pronounced /lu/. After that you start to get into French names like "Cardinal Richelieu". Where did the choice of /ɔɪ/ come from? Euler?

(Spelling pronunciations of Euler as /ju.lɚ/ are common in America, because out of the famous names starting with "Eu-", there's Euler and a bunch of Greeks.)

I remember that South Pacific noted one character as having the quirk of pronouncing "lieutenant" /lɛf.tɛn.ənt/. That seems unlikely to have been a spelling pronunciation, and it obviously isn't standard (or it wouldn't draw comment), but it does remind me of the development of υ into [v] in the Greek diphthongs ευ and αυ.

Philip Taylor said,

April 19, 2022 @ 7:33 am

"I remember that South Pacific noted one character as having the quirk of pronouncing "lieutenant" /lɛf.tɛn.ənt/. That seems unlikely to have been a spelling pronunciation, and it obviously isn't standard" — it's completely standard, Michael, throughout Great Britain and quite possibly throughout much of the English-speaking world. As to "lieu", I pronounce this as /ljuː/ when stand-alone, or as /ljø/ in French-origin words such as banlieue, milieu, Richelieu, etc. Why I thought that "lieutenant" should be pronounced /lɔɪ-tə-nənt/ I have no idea, but at the age of five or so I was probably not exposed to many instances of the "lieu" cluster in writing and so had to make a guess …

Andrew Usher said,

April 20, 2022 @ 9:03 pm

Your pronunciation of 'lieu' with the yod is surely old-fashioned or idiosyncratic; it violates my phonotactic generalisation, and I'm sure that most Brits, no less than Americans, make 'lieu' and 'loo' homophones. Do you really mean /ljø/ and not /ljɜː/ – British speakers are known to conflate the latter with the former, despite its normal lack of rounding (Americans don't have that problem, since we lack /ɜː/ in the first place).

As for 'leftenant', it's certainly not a spelling pronunciation now, but a well-known theory is that its otherwise mysterious origin is as a spelling pronunciation in Middle English, when u and v were not distinguished in writing; reading the latter would produce what would come down to us as 'leave-tenant', and the shortening and voicing assimilation (perhaps encouraged by 'left') are not surprising.

Philip Taylor said,

April 21, 2022 @ 6:42 am

Andrew — Thank you for your comments. As you (and doubtless most other readers of / contributors to) Language Log are aware, there are various aspects of my idiolect which I think of as "conservative" but which you may think of as "old fashioned" — my retention of a yod-glide in "lieu" is undoubtedly one of these, as are my attempts (not always successful) to different between /tju/ (as in "Tuesday") and /tʃu/ (as in "chew"). As regards /ljø/ and not /ljɜː/, I certainly mean /ljø/ in "bonlieue", as the word remains a purely foreign one in British English (although regularly heard on the radio, in the context of the Parisian suburbs), but may well use /ljɜː/ in "milieu" (considerably more assimilated in British English) and "Richlieu" (fully assimilated).

And thank you in particular for the explanation of a possible origin for British English "lieutenant" — I had not encountered this explanation before, but it makes perfect sense (to me, at least). One final note : I wonder whether you noticed in the facsimile recently adduced by Mark Liberman that initial (modern) "u" is invariably printed as "v" [e.g., "vngodlie"] while both medial (modern) "u" and medial (modern) "v" are printed as "u" [e.g., "confusion", "graue"]. "vniuersal" especially stands out. I am not sure that I have noticed this pattern previously.