More post-IPA astronauts

« previous post | next post »

As promised yesterday in "Pronunciation evolution", today I'll present some examples to suggest that Wally Funk's pronunciation of "astronaut" was not a mistake or an idiosyncrasy:

Taking a look at a sample of 100 instances of "astronaut" in the previously-described NPR podcast corpus, I found several similar cases where the word has only two phonetic syllables, with the first ending with a fricative and the second starting with [n]. And in more than half of the cases, the unstressed medial syllable is not elided, but the /t/ vanishes completely, and the /r/ is retained only as spectral lowering at the end of the /s/. I don't have time this morning to lay those examples out and discuss them, but I'll put it on my to-blog list for tomorrow.

We might transcribe Wally Funk's rendition in IPA-ish as [æʃnɔt], though the [ʃ] would be covering a complex tangle of coronal gestures:

Only a few of the 100 pronunciations in the NPR sample had the sequence of phonetic segments implied by Wiktionary's /ˈæstɹəˌnɔt/.

Some were similar to Wally Funk's pronunciation, with only two phonetic syllables and a fairly uniform [ʃ]-ish fricative at the end of the first syllable. Most others involved (gradient) stages on the way to that pronunciation, as in the range of alternative /sts/ renditions described in "On beyond the (International Phonetic) alphabet", 4/19/2018. I'll give just a couple of examples illustrating the range encountered.

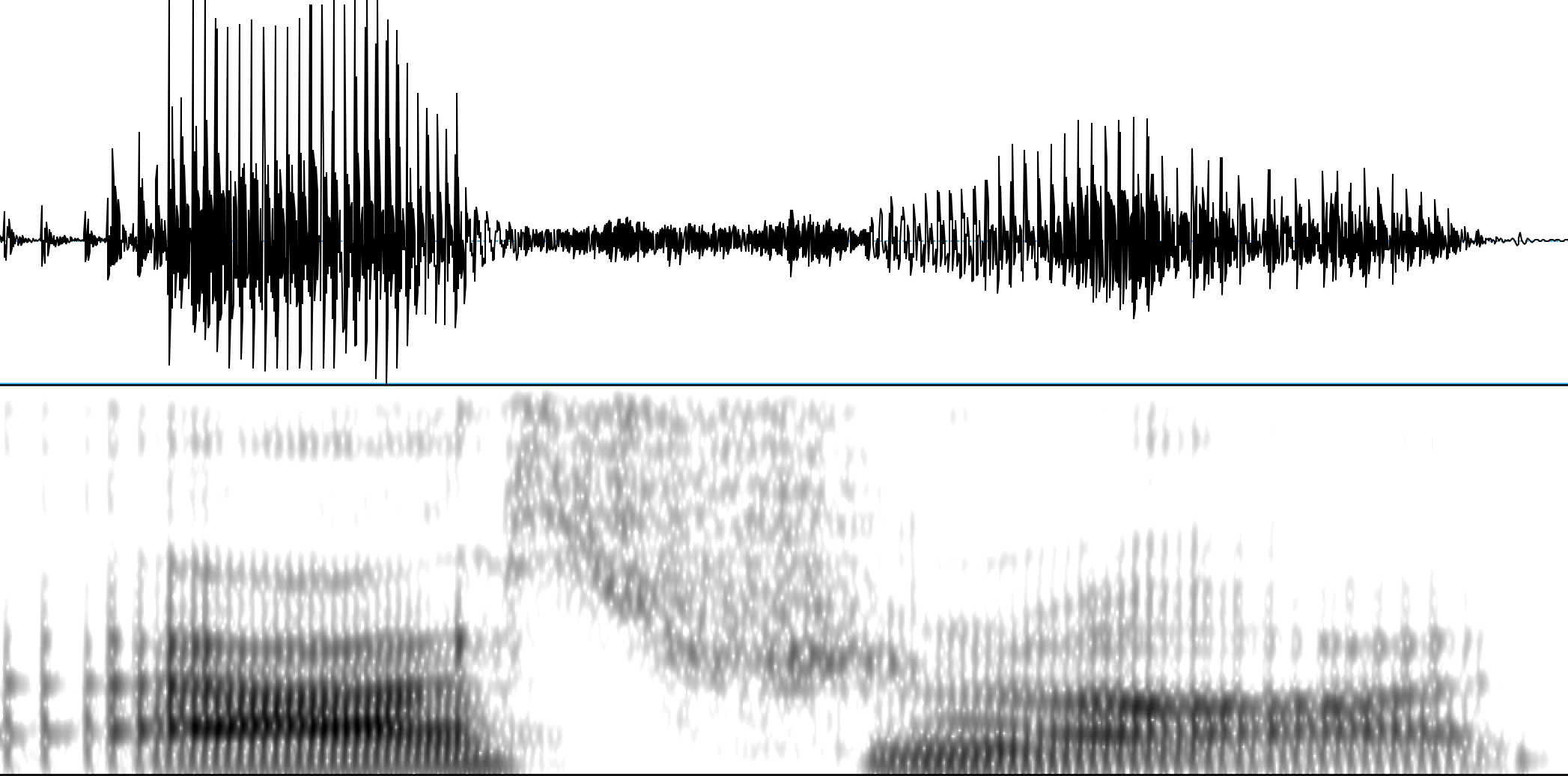

Here's an example from "Who Caused The Mysterious Leak At The International Space Station?", NPR All Things Considered, 9/5/2018. The speaker is Nell Greenfieldboyce.

The sentential context:

Leroy Chao is a former NASA astronaut

who was once commander of the station.

Zeroing in on the word "astronaut":

And splitting the audio at end of the voiceless fricative region:

We might transcribe this in IPA as something like [æsʃrnɔt]. We could add various diacritics and sub- or superscript characters. But again, being forced to reduce the phonetics to a sequence of "segments" is just not helpful.

A few seconds later, Ms. Greenfieldboyce uses the word again:

Alexander Gerst, an astronaut from the European Space Agency,

told Mission Control

that they found a two-millimeter wide hole

in the hull of a Russian spacecraft that's attached to the station.

Zeroing in again, we see the same pattern:

Moving on, here's an example from another NPR host, taken from "Life in Space", NPR Talk of the Nation 8/3/2005. This time the speaker is Neal Conan.

Zeroing in again, we see something like [æsʃɚnɔt]:

Mr. Conan gives us three clear syllables rather than two (and a smidge). But there are no well-defined /t/ and /r/ segments — and my suggestion of [æsʃɚnɔt] again tangles the physics of several overlapping laryngeal and coronal gestures in the [sʃɚ] sequence.

In later installments, I'll follow up on commenters' suggestions about pronunciations of "president" and "social security". But really, just about every sentence spoken by every English speaker presents examples of this issue.

Andrew Usher said,

April 16, 2022 @ 8:18 am

I think Bob Ladd's suggestion to the last post that familiarity plays a role deserves note. It's surely not merely a coincidence that the realisation reduced enough for you to notice came from someone that has probably used and heard the word 'astronaut' much more than most people. Your last clip, by a male speaker not associated with the space program (Conan) sounds quite standard; it takes rather close listening to notice the lack of any distinct /t/ – but it's likely a standard realisation of /str/, remembering that /tr/ in fluent English is never two distinct sounds. [rə] -> [ɚ] is well known to occur in rhotic American English, also.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Philip Taylor said,

April 16, 2022 @ 9:02 am

So Wiktionary has /ˈæstɹəˌnɔt/ where the LPD has /ˈæs trə nɔːt/ — that would seem to explain why you (Mark) originally transcribed Wally Funk's rendition as "ash naught" while I heard (and reported) "ash not".

Andrew Usher said,

April 16, 2022 @ 10:50 am

That is an (irrelevant to this topic) American/British difference in both perception and production. The American THOUGHT is closer to the English LOT in quality, whatever the length; and it was very short here. However, the quality to an American ear (that distinguishes the two) is that of THOUGHT rather than PALM/LOT, and so, this being an American accent, the interpretation 'naught' is correct, and 'not' would not be.

The actual British pronunciation of 'astronaut' (which is phonemically the same as the American) is not relevant to those perceptions.

Cervantes said,

April 16, 2022 @ 10:55 am

Many people have run for the office of Prezneh Yune eye Stay.

Philip Taylor said,

April 16, 2022 @ 11:29 am

"That is an (irrelevant to this topic) American/British difference in both perception and production" — I do not dispute for one second that my comments was "irrelevant to this topic", Andrew, but it is surely not irrelevant to matters linguistic, the one single factor that binds together all threads here, which is why I sought to raise it here rather than on a forum devoted to (say) fly fishing.

Andrew Usher said,

April 16, 2022 @ 12:40 pm

No need to state the obvious. But if we're being so off the topic, I'd like to point out that – quite unintentionally – my parenthetical illustrates the value of the that/which distinction and why I follow it; had I written "(which distinguishes the two)" I would have meant something different, though also true in this case.

The 'that' version means "to a person that …", i.e. as heard by an American that pronounces 'cot' and 'caught' differently, as I do (and standard GA does). The 'which' version would mean "that is what distinguishes …", i.e. it is the quality and not the length that affects American perception of these vowels, as is true of all vowels (except possibly schwa).

Michèle Sharik Pituley said,

April 16, 2022 @ 12:56 pm

I’m confused. Andrew, are you saying that AmE “thought” is not the same sound as AmE “lot”? My topolect has the same sounds for thought, lot, cot, caught, don, dawn, etc. Naught & not sound exactly the same.

Ditto for Mary, merry, marry – bury, berry, barry – ferry, fairy, etc. They all have the same vowel sound. I know how to make them sound different, but only do it when I need to make sure that the distinction is, well, distinct.

(I try to be very careful distinguishing horror from wh*re, but my topolect would ordinarily pronounce them the same (also hoar, though it’s not a common word for me to say. At least the distinction between mirror & meer is not quite so dire.)

Terry K. said,

April 16, 2022 @ 2:51 pm

Some Americans have the caught-cot merger, and for them "thought" and "lot" would have the same vowel, and "naught" and "not" would sound identical. Others of us don't. For me, American without that merger, thought/naught/caught has a rounded vowel. Lot/not/cot has an unrounded vowel, the same vowel as father (father-bother merger).

JPL said,

April 16, 2022 @ 5:42 pm

The general considerations are covered pretty well in the 2018 post. The only thought I might add is that you don't have to describe (you're not restricted to describing) the phonetic phenomena you are interested in using a notational system, since such a system describes the phenomenon in terms of discrete objects, in this case discrete articulatory acts (what Mark calls "articulatory gestures"), and what you are interested in involves a continuum of movements of the vocal organs. So if you are interested in understanding the evolution of the sound system or the "shapes" of the words for a particular language, a direct description of the speakers' articulatory movements using consistently articulatory terminology (not notation) might give you a more accurate picture of what you are after. (The IPA notation, including diacritics and "narrow transcription", is more relevant in the field research process.) In English the requirements of morphological expression result in some phonetic sequences that for English speakers are cumbersome to execute, such as the "-sts-" or the "str-" before an unstressed syllable (compare with the word 'astronomy'), and which will inevitably be reduced (changed), and one is interested in systematic principles for how and why this happens. (Of course what kind of contexts prove cumbersome varies from language to language.) So you would be describing what exactly is happening with the articulatory organs, rather than only what from the speaker's point of view would be their purposeful articulatory acts. (Also, a direct referential description allows for adjustment in pursuit of the mechanisms, while a notation assumes the existence of fixed (intentional) objects.)

[(myl) Let's add the implication for linguistic theory: allophonic variation is not (always? ever?) symbolically mediated. That is, allophonic variation is not properly described as changes in phonological structures, but rather involves variable aspects of the phonetic interpretation of those structures.]

Paul said,

April 26, 2022 @ 12:52 pm

That audio reminded me of a number of UK football (soccer) commentators who leave the – er off "Manchester" when telling us about "ManchestUnited" and "ManchestCity". And most of them don't pronounce the second "s" in "substitute".