Another sinograph for Unicode — the third-person gender-neutral pronoun

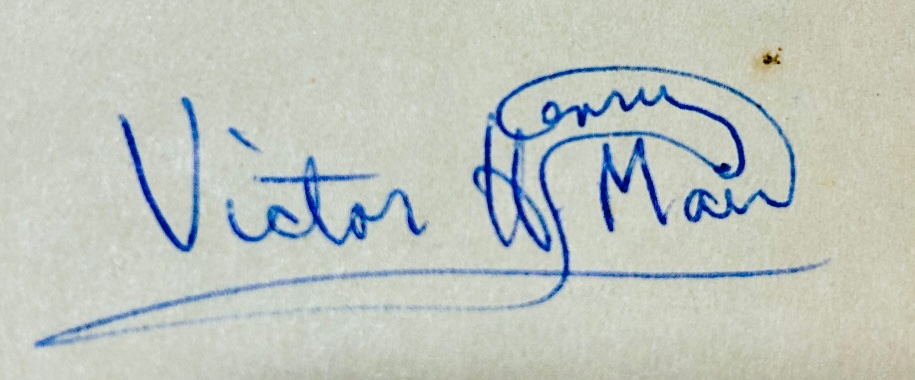

No sooner had I posted about a block of 11,328 proposed Small Seal characters dating back roughly two millennia being incorporated in UNICODE than a single spanking new sinograph surfaced and was urgently put forward for inclusion, and it is causing a bit of a ruckus. That is the third-person gender-neutral pronoun [X也], which is pronounced the same as all the other characters for supposedly gendered Sinitic third-person pronouns, viz., tā (see below for their graphic forms).

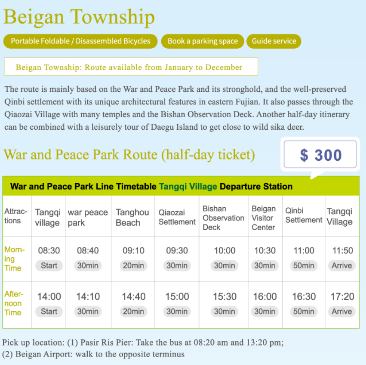

N.B.: The proposed neograph under dicussion is provisionally being written as [X也], but bear in mind that, as I have pointed out countless times, all sinographs, by the exigencies / inherent nature of the script, whether they have 1 stroke or 64 / n strokes, must be squeezed inside the same size box as all other sinographs. In other words, [X也] perforce — once the typographers get it worked out — will eventually have to fit inside exactly the same space as 也 and biáng (you can get an authentic plate of these belt-like Shaanxi noodles at Xi'an Sizzling Woks, 40th & Chestnut in University City next to Penn [opens at 11:30 AM, closed on Tuesdays]). There are many Language Log posts about diverse aspects of this jabberwockyish character. Just look it up under "biang"

Read the rest of this entry »