Archive for July, 2021

July 31, 2021 @ 7:56 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Historical linguistics, Language and history, Morphology, Toponymy

My brother Denis and I have long been intrigued by the use of the prefix yǒu 有 ("there is / are / exist[s]") in a wide variety of circumstances in Old Sinitic: e.g., before the word for family temples (yǒu miào 有廟), before the names of barbaric tribes (yǒu Miáo 有苗), and before place names (yǒu Yì 有易). We wonder whether similar constructions exist in other languages.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 30, 2021 @ 7:07 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Colloquial, Errors, Miswriting, Orthography, Philology, Phonetics and phonology, Reading, Vernacular

I wrote to a colleague who helped me edit a paper that it had been accepted for publication. She wrote back, "I’m glad it is excepted".

Some may look upon such a typo as "garden variety", but I believe that it tells us something profoundly significant about the primacy of sound over shape, an issue that we have often debated on Language Log, including how to regard typographical errors in general, but also how to read old Chinese texts (e.g., copyists' mistakes, deterioration of texts over centuries of editorial transmission, etc.).

Often, when you read a Chinese text and parts of it just don't make any sense, if you ignore the superficial semantic signification of the characters with which it is written, but focus more on the sound, suddenly the meaning of the text will become crystal clear. In point of fact, much of the commentarial tradition throughout Chinese history consists of this kind of detective work — sorting out which morphemes were really intended by a given string of characters.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 29, 2021 @ 10:22 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and sports, Names, Writing systems

Taiwanese weightlifter Kuo Hsing-chun (Guō Xìng-chún 郭婞淳) won a gold medal the other day in Tokyo:

"OLYMPICS/Kuo thrilled at winning Olympic gold, but could be hungry for more", Focus Taiwan (7/28/21)

Mark Swofford observes:

One odd thing about the weightlifter's name is the middle character: 婞. Wenlin gives that as an obscure character for a morpheme for "hate". That, at least for me, is an unexpected meaning, because the parts of the character are clearly, of course, 女 and 幸 — which are used for morphemes for "woman" and "good fortune".

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 28, 2021 @ 1:55 pm· Filed by Mark Liberman under Words words words

A link from Michael Glazer, with the note "Bats have been getting a bad name recently epidemiologically, so it’s nice to hear them mentioned in a positive way": "Nathan Ruiz, "Young bats offer hope…", WaPo 7/27/2021.

Well, OK, the full headline makes the real context clear: "Young bats offer hope as Orioles fall to Marlins". But as Michael observes,

Zoologically, we’ve got three of the Vertebrata subphylum’s seven Classes here. Stuff in Sidewinders and Sharks, and there’s another two. Jawless fishes and amphibians strike me as a bit more challenging in the way of sports team names. The Mar-a-Lago Lampreys? The Calaveras Jumping Frogs? I dunno.

And his closing: "I leave you to identify a linguistics hook!"

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 28, 2021 @ 10:52 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Accents, Language and the law, Pronunciation, Topolects

The focus of this post is the nature and modus operandi of the piànzi 騙子 ("swindler; scammer").

According to this article in Chinese, scammers do not speak good Mandarin because having an "accent" enables them to carry out target screening. Such an argument may seem like a bit of a stretch, but let's see how this supposedly works out through the eyes of two Mandarin speaking PRC citizens who have been the intended victims of the schemes of such piànzi 騙子, who pose as representing banks and other financial institutions, public security bureaus, and so forth.

I

The article suggests that there are three reasons why phone scammers speak in strong topolect accents rather than standard Mandarin:1. Accent serves as a "mechanism of filtration", because those who are not sensitive enough to non-Mandarin accents and who can't recognize what is or is not Mandarin are more prone to fraud. 2. The scammers are simply not capable of speaking standard Mandarin given the current situation of Mandarin popularization in China. The scammers are more likely to be unschooled, and they usually share the same accent. 3. It is because of the high illiteracy rate in China that many people can't tell frauds from reliable phone calls made by authentic institutions.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 27, 2021 @ 12:39 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and computers, Writing systems

Phil H wrote these comments to "Uncommon words of anguish" (7/18/21):

The anguish is very real. My wife had a character in her name that most computers will not reproduce ([石羡]), despite it being relatively common in names in our part of the world, and has been refused bank accounts, credit cards, and a mortgage because of it. In the end she changed her name rather than continue to deal with the hassle. The character is in the standard, but it was too late for us.

…there have always been ways to get the character onto a computer, but any given piece of bank software might not recognise it, and any given bank functionary might be unfamiliar with them. We then had trouble when some organisations used the pinyin XIAN in place of the character, but that then made their documentation inconsistent with her national ID card (which had the right character on it) and so yet further bodies would not accept them… It was the standard "mild computer snafu + large inflexible bureaucracy = major headache" equation.

An anonymous correspondent, a computer scientist, sent in the following remarks:

Phil H is talking about a character which is in a "supplementary plane" in Unicode (and similarly in GB-18030). Unfortunately, an awful lot of software was only ever tested on Basic Multilingual Plane characters.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 26, 2021 @ 4:35 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and medicine, Semantics, Signs, Translation

Sign in Vancouver International Airport:

Segregated line-ups for vaccinated and unvaccinated international arrivals at Vancouver International Airport. Photo by Andrew Aziz. (Source)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 26, 2021 @ 8:13 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Classification, Language and politics, Topolects

Paul Goble has an article in Window on Eurasia — New Series (7/24/21) that is short, succinct, and significant enough to quote in its entirety: "Despite Putin’s Words, Moscow Does Recognize the Ukrainian Language as Distinct, Yaroshinskaya Says":

Staunton, July 17 – All[a] Yaroshinskaya, a senior Moscow commentator who was politically active at the end of Soviet times and the beginning of Russian ones, says that whatever Vladimir Putin says about Russians and Ukrainians being one people, even he has been forced to recognize that a separate Ukrainian language has existed for a long time.

Beyond question, Putin wants Ukrainians to speak Russian; but his discussion of the history of Russian-Ukrainian relations unintentionally calls attention to Russian efforts from the 18th century up to now of Moscow’s efforts to restrict Ukrainian, an acknowledgement of its existence and power (rosbalt.ru/blogs/2021/07/15/1911461.html).

Again and again the tsars and the commissars and now “democratic” Russian leaders have tried to restrict Ukrainian and get Ukrainians to speak Russian. Yaroshinskaya details the decrees and decisions of Russian rulers from the times of Peter the Great to the present; and she points as well to the single exception until now.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 26, 2021 @ 5:10 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Alphabets, Elephant semifics, Errors, Information technology, Lost in translation

[This is a guest post by Bernhard Riedel]

I stumbled across what was probably a mis-MT in the context of the Olympic Games. (article in Korean)

"During a foot kick on the way to the gold medal, some hangul became visible. But…"

On the black belt of the athlete from Spain, one can see "기차 하드, 꿈 큰" which is wonderful gibberish. Netizens in Korea were puzzled but also quick to guess an erroneous machine translation.

기차(汽車): (railway) train (definitely *not* related to "to train")

하드: (en:hard, transliterated)

꿈: dream (noun built from the verb 꾸다(to dream) with the nominalizer ㅁ/음)

큰: big (from the verb 크다) in the form used when modifying a noun that follows

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 25, 2021 @ 7:00 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Language and archeology, Language and history, Language and literature, Language and religion

Here at Language Log we know our Ossetes and have been learning much about Scythians (see "Selected readings"), so it is good to have this new (forthcoming) book by Richard Foltz:

The Ossetes: Modern-Day Scythians of the Caucasus

New York / London: I. B. Tauris / Bloomsbury, 24 February 2022

Publisher's description:

The Ossetes, a small nation inhabiting two adjacent states in the central Caucasus, are the last remaining linguistic and cultural descendants of the ancient nomadic Scythians who dominated the Eurasian steppe from the Balkans to Mongolia for well over one thousand years. A nominally Christian nation speaking a language distantly related to Persian, the Ossetes have inherited much of the culture of the medieval Alans who brought equestrian culture to Europe. They have preserved a rich oral literature through the epic of the Narts, a body of heroic legends that shares much in common with the Persian Book of Kings and other works of Indo-European mythology. This is the first book devoted to the little-known history and culture of the Ossetes to appear in any Western language. Charting Ossetian history from Antiquity to today, it will be a vital contribution to the fields of Iranian, Caucasian, Post-Soviet and Indo-European Studies.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 23, 2021 @ 4:14 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Colloquial, Grammar, Idioms, Semantics, Syntax

The particle "ge 個/个" is one of the most frequent characters in written Chinese (12th in a list of 9,933 unique characters). It is generally thought of as a classifier, numerary adjunct, measure word. Indeed, it functions as the almost universal, default classifier when you're not sure what the correct / proper measure word for a given noun should be. In addition, "ge" has more than a dozen other definitions and usages, for which see Wiktionary. However, I'm not sure that any dictionary or grammar accounts for a very special usage that I have long been intrigued and enchanted by, namely the "ge" in this type of sentence:

Wǒ máng de gè yàosǐ

我忙得個要死!

"I'm so busy I could die!", i.e., "I'm incredibly busy!"

Here de 得 is a particle marking the complement of degree.

Because I lived with a big household full of Chinese (Shandong) in-laws, I picked this construction up very early in my learning of spoken Mandarin, but I always had a visceral feeling that it was extremely colloquial and unlikely to be encountered in written texts and was probably not covered in conventional grammars. So I asked around among colleagues and native speaker informants how they would explain this unusual "ge", grammatically or otherwise. Here are some of the replies I received.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

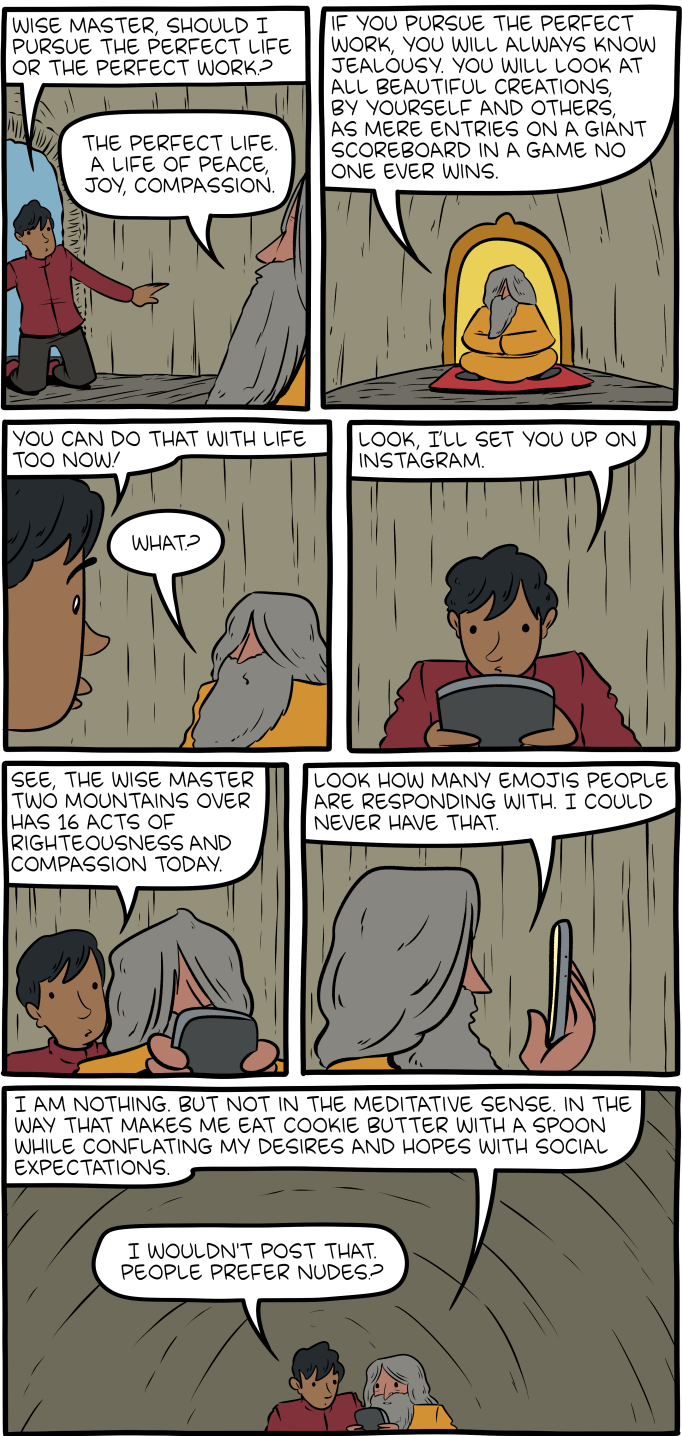

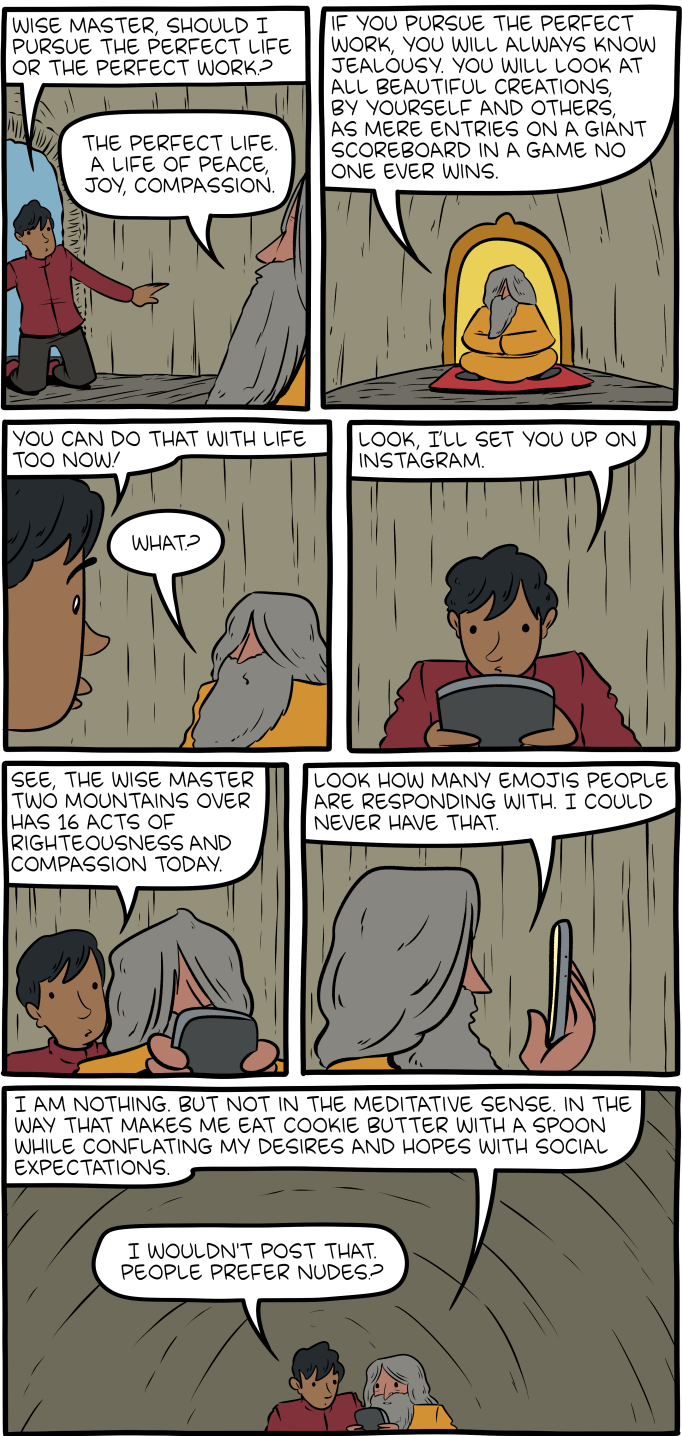

July 23, 2021 @ 5:46 am· Filed by Mark Liberman under Linguistics in the comics

Recently on SMBC:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink