Dangerous heights and tipping vessels

Chris Button says that he was looking at the oracle-bone form for wēi 危 ("precarious, precipitous; perilous; high; ridge [of a roof]; dangerous") and noticed that Huang Dekuan (2007 mammoth dictionary of ancient forms of characters) treats it as depicting a qīqì 欹器 ("tilting vessel" or "tipping vessel"). This was:

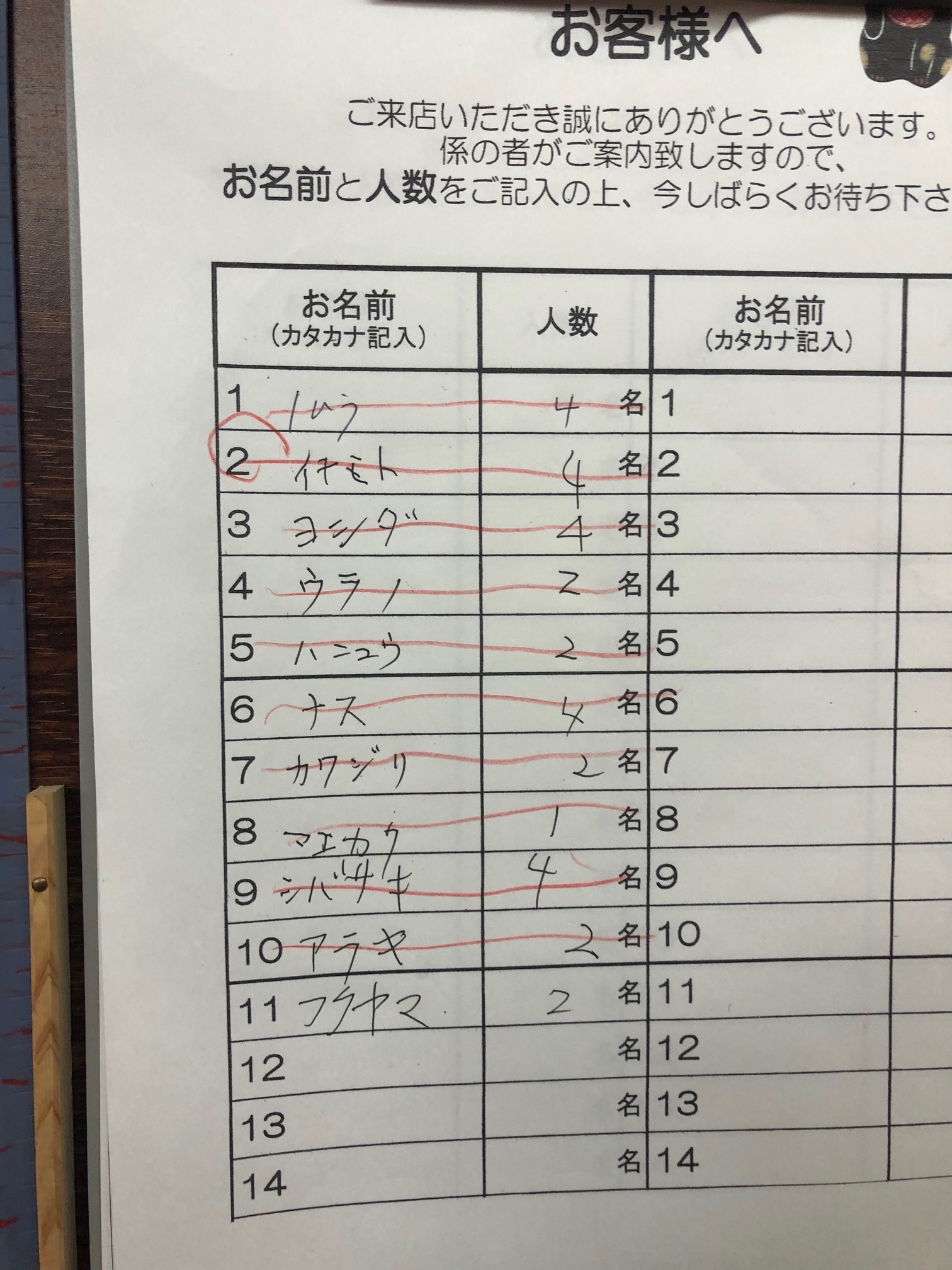

…an ancient Chinese ceremonial utensil that automatically overturned and spilled its contents once it reached capacity, thus symbolizing moderation and caution. Both Confucian and Daoist Chinese classics include a famous anecdote about the first time Confucius saw a tilting vessel. In the Confucian tradition (e.g., Xunzi) it was also named yòuzuò zhī qì (宥座之器, "vessel on the right of one's seat"), with three positions, the vessel tilts to one side when empty, stands upright when filled halfway, and overturns when filled to the brim—illustrating the philosophical value of the golden mean. In the Daoist tradition, the tilting vessel was named yòuzhī (宥卮, "urging goblet" or "warning goblet"), with two positions, staying upright when empty and overturning when full—illustrating the metaphysical value of emptiness, and later associated with the Zhuangzian zhīyán (卮言, "goblet words") rhetorical device.

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »