Vietnamese without diacritics

« previous post | next post »

From Reddit:

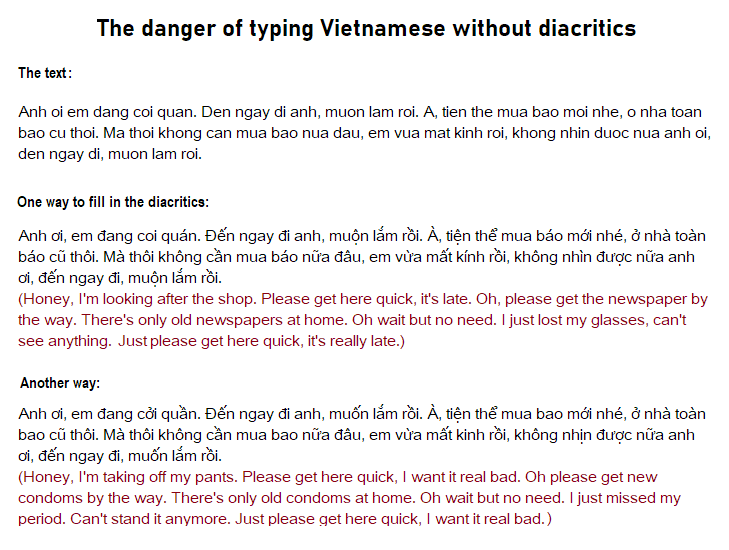

[Click to embiggen]

From Bill Hannas:

My [Vietnamese] wife Jennifer read the passages in less time than it took me to read the corresponding English. She says both are completely intelligible, albeit it in different ways, with the different diacritics. A smile crept over her face immediately when she started on the second passage.

I ran a check on it myself and agree. Both can be read as per the English translations.

The problem is the underlying text(s) is forced. It was chosen specifically to allow two interpretations. Normally one can read simple (email-style) Vietnamese without diacritical markings with no ambiguity, although today's input methods will automatically populate the correct orthography much the same way pinyin input yields a menu of likely character choices.

My point here is no one should make a big deal about this contrived example. It has zero relevance to any serious linguistic debate that I know of.

From what my colleague says in the last clause of the penultimate paragraph, it sounds as though most Vietnamese don't bother with the diacritics when typing, but let the input system add the appropriate diacritics for them, just as when I and nearly everyone I know type Chinese, we simply type toneless Hanyu Pinyin and let the IME add the tones, choose the characters, and even parse words. Sophisticated systems like Google Translate, which I use, do this with an astonishingly high level of accuracy and require only minimal human correction. It seems as though IMEs for Vietnamese have achieved similar levels of proficiency in adding diacritics, without having to select appropriate characters.

Selected readings

- "Diacriticless Vietnamese on a sign in San Francisco" (9/30/18)

- "Words in Vietnamese" (10/2/18)

- "Vietnamese nail shop" (10/21/18)

- "The inevitability (or not) of diacritical marks" (10/23/18)

- "Diacriticless Vietnamese, part 2" (10/27/18)

- "German with pseudo-Vietnamese diacritics" (4/12/18)

- "Fancy diacritics" (3/5/20)

[Thanks to Ian Barrere]

Mark Liberman said,

March 16, 2020 @ 9:50 pm

See "Noi lai and contrepets", 1/8/2005:

You can think of nói lái as subversive communication by means of implied speech errors. For example, in the period after the fall of Saigon to the communists in 1975, residents would say of the obligatory picture of Ho Chi Minh that they would like to "lộng kiếng" = "frame (it in) glass", by which they meant that they would like to "liệng cống" = "throw (it in the) sewer".

mollymooly said,

March 17, 2020 @ 12:09 am

Wikipedia's IME article could use some expert attention.

maidhc said,

March 17, 2020 @ 10:41 pm

I believe I posted here my experience a couple of years ago, when I entered some toneless pinyin into Google Translate and received back a torrent of meaningless gibberish. But perhaps things have improved since.

When you encounter Vietnamese names in the West, they almost always come without diacritics. This opens up a wide variety of possible errors. Vu is a common name, but if you say it with the wrong tone it means "breast". D with a line through is like English D but without the line it is like Z. (I saw film of Pres. Kennedy talking with his advisors, and I was a bit surprised to hear him talk about Pres. "Ziem" of South Vietnam.)

Putting in the diacritics wouldn't help much. The Vietnamese don't need them, and non-Vietnamese speakers probably can't interpret them anyway. And most of us wouldn't spend the time to master things like the "creaky rising tone". I once thought it would be a good project to learn to pronounce Vietnamese names semi-correctly, but I finally concluded it was too challenging–you would have to really make a serious effort to learn the language to get anywhere.

It sounds like Vietnamese would be a great language for puns. Is there an equivalent of The Two Ronnies in Vietnam?

Philip Taylor said,

March 17, 2020 @ 11:54 pm

Maidhc — The Vietnamese, like the Chinese, adore television comedy, so I am sure that there are Vietnamese "Two Ronnies" clones. Vietnamese "D" without bar is indeed like "Z" in the North, but in the South it is more like "Y" (where "Y" = /j/). If by 'the "creaky rising tone"' you mean dấu ngã, then it is not hard to master, but beware — if you use it when speaking to a Vietnamese (even if you just pronounce a place name such as Đà Nẵng correctly), he/she will immediately assume that you speak the language fluently !

Chris Quyết said,

March 19, 2020 @ 12:38 am

Vietnamese don't let an input system add diacritics, they either input them manually, leave them out entirely or add sparing to avoid confusion. Typing with the 'Unikey' keyboard for diacritics is so second nature, a lot of short hand uses the 'raw characters' that add diacritics. For example terminal S = rising tone, so mới is shortened to 'ms', cũng to 'cx', etc.

Chris Quyết said,

March 19, 2020 @ 12:46 am

maidhc,

While D is /z/ in the North and /j/ in the South, Z is pronounced as /j/ all over, probably an influence from Vietnamese speakers of French. I have no idea why it represents /j/ and not /z/, but it is frequently used for Southern pronounciation of V in the South, which is colloquially /j/. So vậy is written as zậy to sound more colloquial.

So Diệm and Dũng may have written their names as Dziem and Dzung to avoid /d/ and represent their local /j/.

Chris Quyết said,

March 19, 2020 @ 12:49 am

Or perhaps Z was created to represent /ʐ/ which was a seperate phoneme but has now merged with or is interchangable with /j/ or /r/ depending on the speaker.