Archive for Language and animals

August 13, 2022 @ 8:43 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Animal behavior, Dictionaries, Etymology, Language and animals, Phonetics and phonology, Pronunciation

In the summer of 1990, I spent a memorable five weeks at the outstanding summer institute on Indo-European linguistics and archeology held by DOALL (at least that's what we jokingly called it — the Department of Oriental and African Languages and Literatures) of the University of Texas (Austin). The temperature was 106º or above for a whole month. Indomitable / stubborn man that I am, I still insisted on going out for my daily runs.

As I was jogging along, I would come upon squirrels doing something that stopped me in my tracks, namely, they were splayed out prostrate on the ground, their limbs spread-eagle in front and behind them. Immobile, they would look at me pathetically, and I would sympathize with them. Remember, they have thick fur that can keep them warm in the dead of winter.

I assumed that these poor squirrels were lying with their belly flat on the ground to absorb whatever coolness was there (conversely put, to dissipate their body heat). At least that made some sort of sense to me. I had no idea what to call that peculiar, prone posture. Now I do.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 3, 2022 @ 8:08 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Metaphors

Someone referred to Pelosi's visit to Taiwan as "foolhardy". That prompted the following response from a sensitive and perceptive Chinese observer:

Foolhardy – reminds me of the phrase, cuàn fǎng 竄訪, used to report Pelosi's visit in all official Chinese news / channels. Whether appropriate or not, I have to marvel at how the single word 竄, both its graph and sound, conjures up an image of reckless rats scurrying. There are people good at wording for the purpose of controlling.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 24, 2022 @ 4:50 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and animals, Language and biology

The giraffe is such an outlandish animal that many otherwise sensible people have thought that it must be a combination of several species.

From the concept of a giraffe being an amalgam of several animals jointly; compare Persian شترگاوپلنگ (šotorgâvpalang, “giraffe”, literally “camel-ox-leopard”) and Ancient Greek καμηλοπάρδαλῐς (kamēlopárdalis, “giraffe”).

Noun

زَرَافَة • (zarāfa) f (plural زَرَافَات (zarāfāt))

-

- group of people, cluster of people, body of people

-

زَرَافَاتٍ وَوُحْدَانًا ―

zarāfātin wa-wuḥdānan ―

jointly and severally; in groups and alone

(source)

The name "giraffe" has its earliest known origins in the Arabic word zarāfah (زرافة), perhaps borrowed from the animal's Somali name geri. The Arab name is translated as "fast-walker". In early Modern English the spellings jarraf and ziraph were used, probably directly from the Arabic, and in Middle English orafle and gyrfaunt, gerfaunt. The Italian form giraffa arose in the 1590s. The modern English form developed around 1600 from the French girafe.

"Camelopard" is an archaic English name for the giraffe; it derives from the Ancient Greek καμηλοπάρδαλις (kamēlopárdalis), from κάμηλος (kámēlos), "camel", and πάρδαλις (párdalis), "leopard", referring to its camel-like shape and leopard-like colouration.

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 21, 2022 @ 5:53 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Animal communication, Intonation, Language and animals, Language and music, Phonetics and phonology

I live in a duplex. Even though the two houses are separated by a thick brick wall, I sometimes hear sounds coming from my neighbor's place. The most conspicuous are the vocalizations made by her dog, Izzy.

Izzy is some kind of South Carolina coon hound. We live in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, but my neighbor got her female dog from a rescue service in South Carolina.

Izzy is quirky. She is unique. I have never heard any other dog like her. She doesn't just bark; she talks. Izzy's voice projects emphasis, querulousness, inquiry, complaint, displeasure, joy, dismay, and a whole range of other emotions and intentions. Sometimes she seems to be talking to herself (muttering and mumbling), and sometimes she seems to be communicating with her owner or other people around her.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 18, 2022 @ 5:33 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and animals, Language and archeology, Language and culture, Language and ethnicity, Language and food, Names

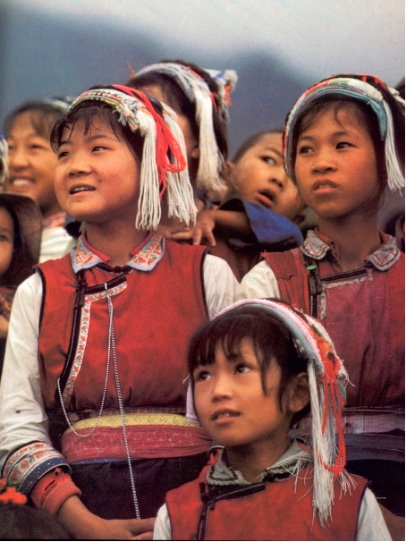

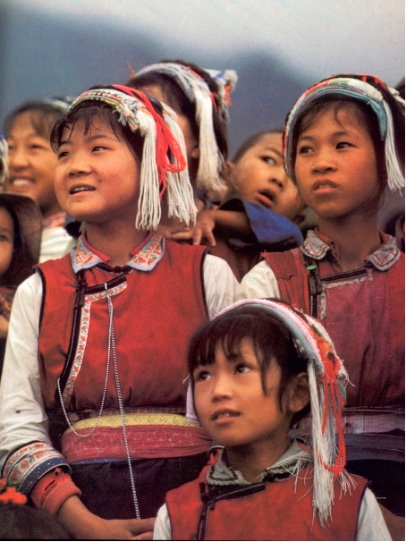

The province of Yunnan in the far south is home to more ethnic minorities and languages than any other part of China (25 out of 56 recognized groups, 38% of the population). The Bai are one of the more unusual groups among them.

Bai children—in Yunnan, China

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 2, 2022 @ 9:27 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and animals, Language and biology, Language and culture, Phonetics and phonology, Semantics

From Chau Wu:

I have always wondered about the deep gulf of variations in the sounds of "néng 能 -bearing" characters, that is, the variations in the onsets and rimes (shēng 聲 and yùn 韻):

néng 能 n- / -eng (Tw l- / -eng) [Note: 能 orig. meaning 'bear'; nai, an aquatic animal; thai, name of a constellation 三能 = 三台]

xióng 熊 x- (Wade-Giles: hs-) / -iong [熊 Tw hîm; the x- in MSM xióng is due to sibilization of h- caused by the following -i.]

pí 羆 ph- / -i (the closely related p- onset is also seen in 罷, 擺)

nài 褦 n- / -ai (the same onset n- is seen in 能)

tài 態 th- / -ai (the same th- onset is seen in 能)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

September 23, 2021 @ 11:15 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Language and medicine, Translation

Victor Steinbok reports:

This made the rounds on Reddit a few times. The screenshot of a 2019 Reddit thread popped up on my FB feed today. It might even come in white and red 😈

Source: NV Debao Winery Magical Penis Wine

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

September 21, 2021 @ 5:07 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Dialects, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and animals, Morphology, Topolects

In various publications and Language Log posts over the years, I have collected scores of old polysyllabic words (e.g., those for reindeer, phoenix, coral, spider, earthworm, butterfly, dragonfly, balloon lute, meandering / winding, etc.), which proves that Sinitic has never been strictly monosyllabic, although that is a common misapprehension, even among many scholars. The reason I call the one featured in this post "another early polysyllabic Sinitic word" is because I don't think I've ever pointed it out before.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

May 19, 2021 @ 11:16 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Verb formation

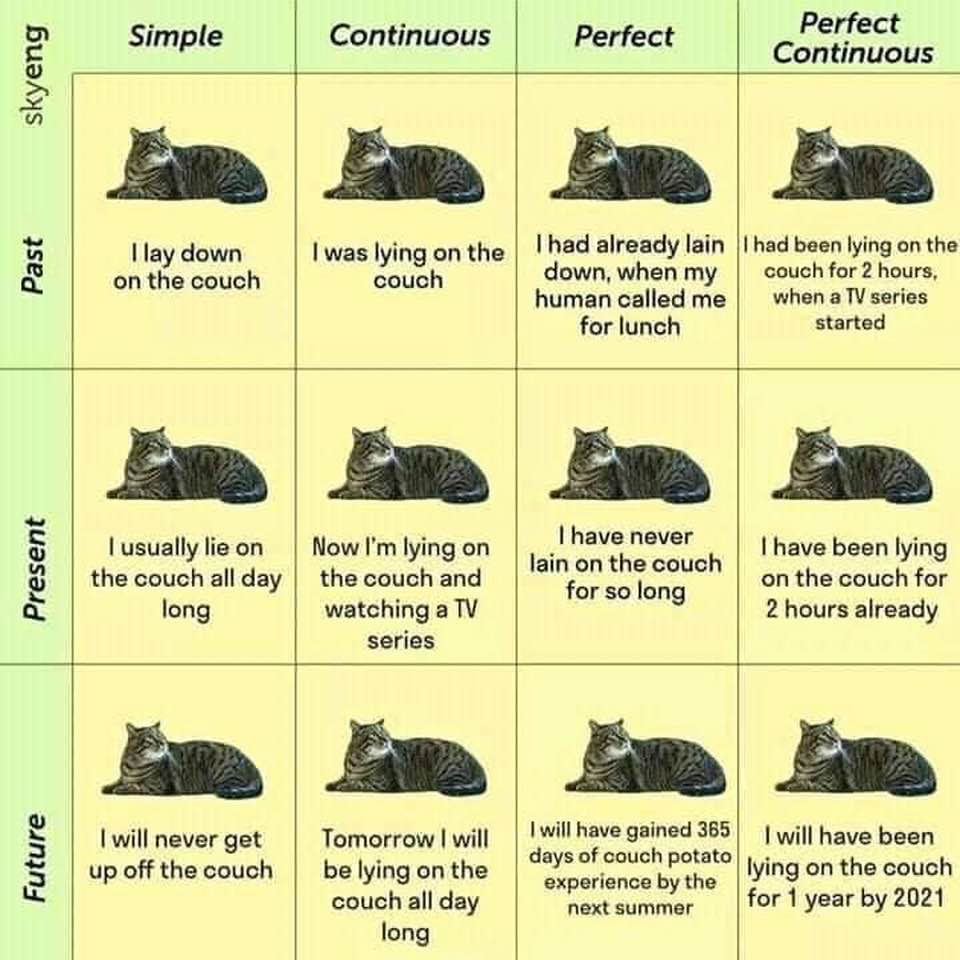

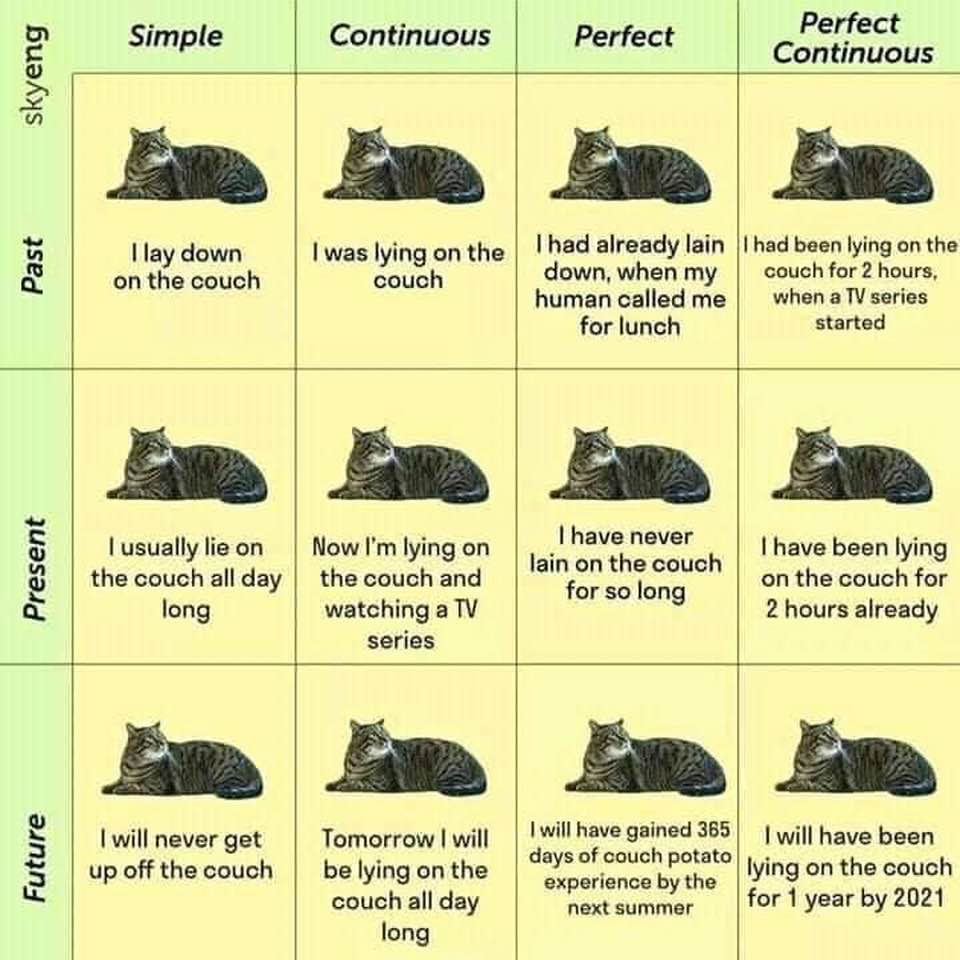

From a Duolingo chat page:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 12, 2021 @ 5:30 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Language and archeology, Language and culture, Language and history, Language and technology

We all know about the Silk Road (which is actually a recent term), and some of us also know about the Bronze Road, the Iron Road, the Horse and Chariot Road, the Fur Road, the Glass Road, the Spice Road, and the Tea Road. Now we really have to take seriously the existence of a Wool Road.

As I have often noted, I began my international investigation of the mummies of the Tarim Basin as a genetics project in 1991, since that was around the time that it became possible to study ancient DNA. After four years of diligent collection and analysis, I grew disenchanted with the expected precision of genetics research, and in 1995 I returned to Eastern Central Asia (ECA) with Elizabeth Barber and Irene Good, prehistoric textile specialists, to study the archeologically recovered textiles of the region. The results of their work turned out to yield tremendously valuable and revealing results about the origins and technology of the ancient textiles we examined.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 11, 2021 @ 8:12 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Language and archeology, Language and culture, Language and religion, Language and the military, Reconstructions

[This is a guest post by Chau Wu, with additions at the bottom by VHM and others]

On the akinakes* (Scythian dagger / short sword) and Xiongnu (Hunnish) horse sacrifice

Chinese historical records suggest that the akinakes, transliterated from Greek ἀκῑνάκης, may be endowed with spiritual significance in the eyes of ancient Chinese and Northern Barbarians, for it was used in solemn ceremonies. Let me cite two recorded ceremonies and a special occasion where an akinakes is used to “finesse” an emperor.

In the Book of Han (漢書), Chapter 94 B, Records of Xiongnu (匈奴傳下), we see an akinakes is used in a ceremony sealing a treaty of friendship between the Han and Xiongnu. The Han emissaries, the Chief Commandant of charioteers and cavalry [車騎都尉] Han Chang (韓昌) and an Imperial Court Grandee [光祿大夫] Zhang Meng (張猛) visited the Xiongnu chanyu** (單于) [VHM: chief of the Xiongnu / Huns] in 43 BC. Han and Zhang, together with the chanyu and high officials, climbed the eastern hill by the river Nuo (諾水)***, killed a white horse, and the chanyu using a jinglu knife (徑路刀) and a golden liuli**** (金留犁, said to be a spoon for rice) mixed the horse blood with wine. Then they drank the blood-oath together from the skull of the King of Yuezhi, who had been defeated by the ancestor of the chanyu and whose skull had been made into a goblet. Essentially, this jinglu knife was a holy mixer.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

November 25, 2020 @ 9:58 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and animals, Language and archeology, Language and culture, Language and history, Writing, Writing systems

Anyone who has studied the history of writing in China is aware that the earliest manifestation of the Sinitic script dates to around the 13th century BC, under the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1600- BC). It is referred to as jiǎgǔwén 甲骨文 ("oracle bone writing") and was used primarily (almost exclusively) for the purpose of divination. The most ideal bones for this purpose were ox scapulae, since they were broad and flat, and had other suitable properties, which I shall describe below.

The bones used for divination were prepared by cleaning and then having indentations drilled into their surface, but not all the way through. A hot poker was applied to the declivities, causing cracks to radiate from the heated focal point. This cracking was called bǔ卜, a pictograph of the lines that form in a heat-stressed bone.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

November 18, 2020 @ 7:15 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and animals, Language and culture, Language and religion

I was just thinking how important cows (and their milk) are for Indian people and was surprised that's reflected in such a fundamental word for a family relationship as "daughter" — at least in the popular imagination. Even in a scholarly work such as that of D.N. Jha, The Myth of the Holy Cow (New Delhi: Navayana, 2009), p. 28, we find:

Some kinship terms were also borrowed from the pastoral nomenclature and the daughter was therefore called duhitṛ (= duhitā = one who milks).

That somehow seemed too good to be true, a bit dubious on the surface. To test the equation, I began by bringing together some basic linguistic information acquired on a preliminary web search.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink