Archive for Language and religion

June 4, 2023 @ 10:48 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Books, Etymology, Language and archeology, Language and history, Language and literature, Language and religion, Translation

I was stunned when I read the following article in the South China Morning Post, both because it was published in Hong Kong, which is now completely under the censorial control of the People's Republic of China (PRC) / Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and because it raises some disturbing political issues and troubling linguistic problems.

"Why the rewriting of China’s history 3,000 years ago still matters today"

Confucius uncovered the truth of the Shang dynasty but agreed with King Wen and the Duke of Zhou to cover up disturbing facts

Beijing’s claimed triumph over Covid-19, for instance, may not echo with all who endured the draconian quarantines.

Zhou Xin, SCMP (4/25/23)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 16, 2023 @ 7:25 am· Filed by Mark Liberman under Computational linguistics, Language and religion

A VentureBeat story by Michael Kerner, "Cohere expands enterprise LLM efforts with LivePerson partnership" (4/11/2023), leads with this image:

…memetically referencing a widely-reproduced detail from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel fresco Creazione di Adamo:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 9, 2023 @ 10:42 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Books, Language and religion

Article in Taiwan News (4/9/23):

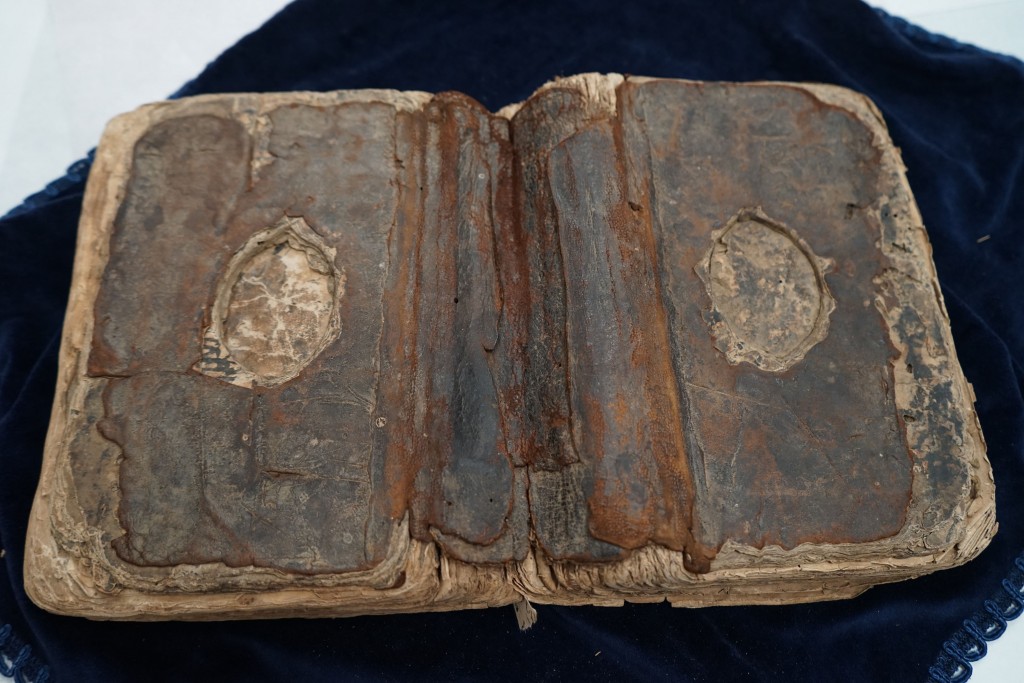

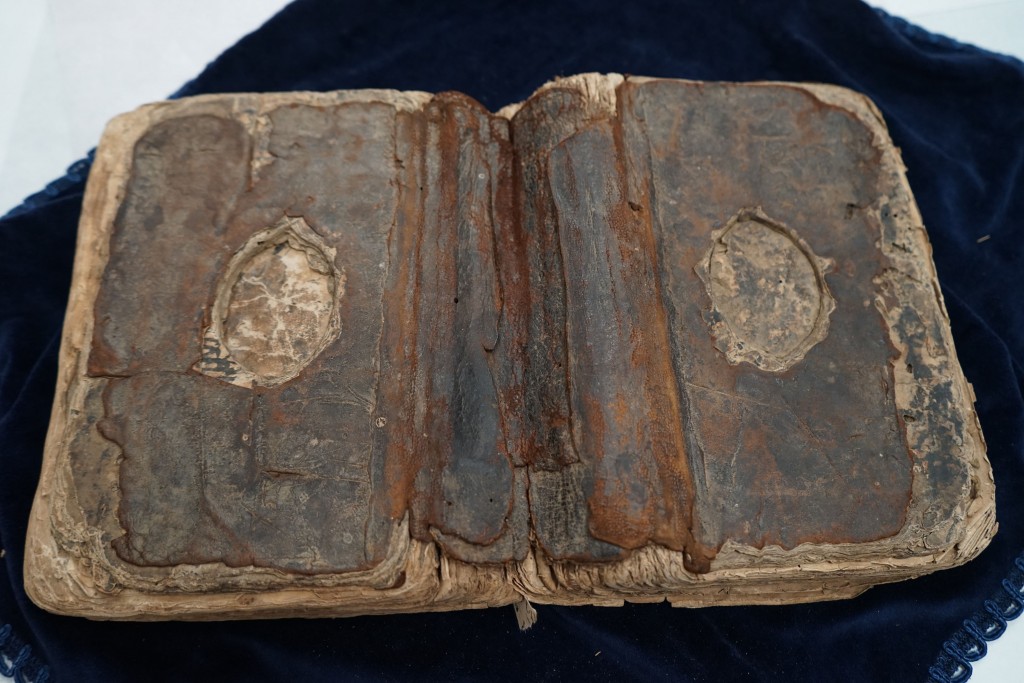

National Taiwan Library repairs 500-year-old Quran

'Book Hospital' tasked with repairing ancient Quran damaged by time, elements

By Sean Scanlan

500-year-old Quran being repaired (CNA photo)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 27, 2023 @ 8:35 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Historical linguistics, Language and history, Language and religion, Topolects, Toponymy

From Rostislav Berezkin, who teaches at Fudan University:

The place where I stay is called Qibao town, now Minhang district of Shanghai. The name means "Seven Treasures". It comes from the name of the Buddhist temple called Qibaosi. Legend says that the temple was built by the Lu family to commemorate Lu Ji* and Lu Yun, brothers of the 3rd cent. AD who were very famous poets and politicians. Their tombs were located there. It became known as Lubaosi (Precious Temple of Lu). But 500 years later the king of Wuyue (907-978) during the Ten Kingdoms (907-979) period visited the place. When he asked the name of the temple, he misheard it as "Six Treasures Temple"; "six" is pronounced somewhat like "lok" in modern Shanghainese (it's "luc" in modern Vietnamese, also an equivalent of the "entering" tone). Apparently this is very close to the medieval pronunciation of the Lu surname ("[main]land"). The king was perplexed because there are seven treasures in Buddhism, not six. Therefore, he decided to donate the precious manuscript of the Lotus Sutra in gold letters he had made before, so that it would constitute the seventh treasure. Then the monastery became known as the Qibaosi.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 8, 2023 @ 8:19 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Etymology, Language and religion, Lexicon and lexicography

I'm often surprised by the number of terms in modern Japanese that have their roots in ancient Buddhist usage. Some of the most common ones are introduced in this article by Brendan Craine from The Japan Times (2/2/23):

"The Buddhist terms that find their way into everyday conversation"

A good example is aisatsu あいさつ / 挨拶:

[noun] a greeting, a salutation, a polite set phrase

[noun] an address given at an official function or ceremony

[noun] greetings or respects such as given at holidays or funerals

[verb] to greet, to say hello, to address

This derives from ichiaiissatsu / いちあいいっさつ / 一挨一拶: "dialoging (with another Zen practitioner to ascertain their level of enlightenment)" (source).

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 2, 2023 @ 1:56 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and culture, Language and religion, Lost in translation, Spelling

From the Facebook account of Mei Han:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 11, 2023 @ 12:20 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Artificial intelligence, Language and archeology, Language and religion

In a masterful Smithsonian Magazine (January-February 2023) article, Chanan Tigay documents:

How an Unorthodox Scholar Uses Technology to Expose Biblical Forgeries: Deciphering ancient texts with modern tools, Michael Langlois challenges what we know about the Dead Sea Scrolls

This engrossing account is so rich that I can only touch on a few of the highlights. It's about a would-be, and to some extent still is, rock musician — looking like the bassist from Def Leppard — named Michael Langlois. But, at 46, "he is also perhaps the most versatile—and unorthodox—biblical scholar of his generation."

What makes Langlois so special? Reading through Tigay's article, it is his relentless quest to get to the bottom of puzzles posed by tiny details of the Dead Scrolls, and his creativity in devising unconventional tools and approaches for doing so.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 9, 2023 @ 7:11 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Acronyms, Language and religion, Language and the movies, Memorization

From TIC Redux:

In the 1971 British dark comedy horror film "The Abominable Dr. Phibes", the title character (played by a scenery-chewing Vincent Price) elaborately kills his victims through torturous deaths inspired by the ten (or so?) Plagues of Egypt… More than once in the film, those biblical plagues are referred to (per closed-captioning) as "the G'Tach"… That term intrigues me, but I've never been able to find any uses of, or references to, it except in connection with this film… Is it a real word?…

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 2, 2023 @ 9:49 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and animals, Language and food, Language and religion

We have been discussing the Yiddish word "glat", albeit with a lot of loose ends (see "Glat perch and medicare yam" (12/19/22). Having gained some additional information, it is worthwhile taking another look.

From a colleague:

I am very familiar with the word Glat, or Glatt. It is often used together with the word kosher. Glatt is Yiddish for "smooth". This word relates to meat and poultry and is never used with fish. Perhaps Chinese borrowed this word because Israel exports food items to China, including fish?

What Is Glatt Kosher?

For meat to be kosher, it must come from a kosher animal slaughtered in a kosher way. Glatt kosher takes it further; the meat must also come from an animal with adhesion-free or smooth lungs.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

December 24, 2022 @ 2:13 pm· Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and religion

Permalink

November 18, 2022 @ 4:22 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and religion

I've always been intrigued by this odd character: 祆. It's got a "spirit; cult" semantophore (radical; classifier) on the left (shì 礻) and a "heaven" phonophore (tiān 天) on the right. Read "xiān", it is customarily translated as "deity; divinity; Heaven" and is thought of as the central figure of Xiānjiào 祆教 ("xian doctrine / religion"). The traditional Chinese explanation of Xiānjiào 祆教 is Bàihuǒjiào 拜火教 ("fire-worshipping doctrine / religion"), which is rendered into English as "Zoroastrianism" or "Mazdaism". According to zdic, Xiān is Ormazda, god of the Zoroastrians; extended to god of the Manicheans.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

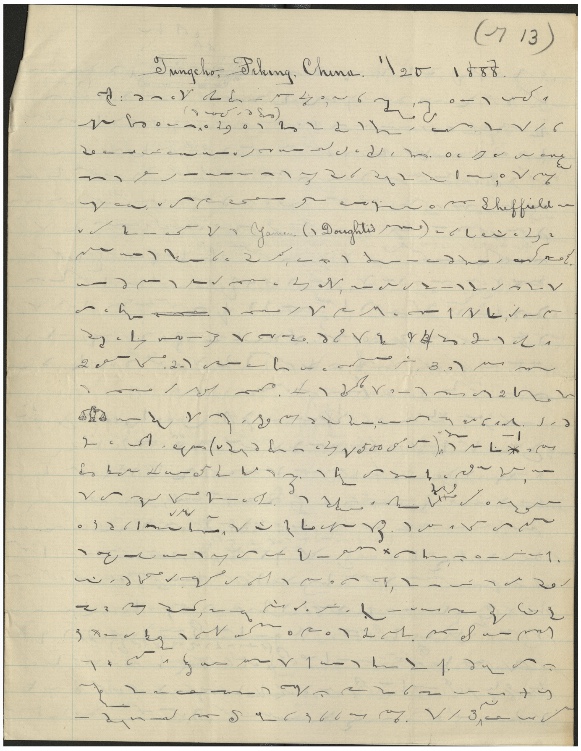

October 27, 2022 @ 12:22 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Decipherment, Language and medicine, Language and religion, Translation, Writing

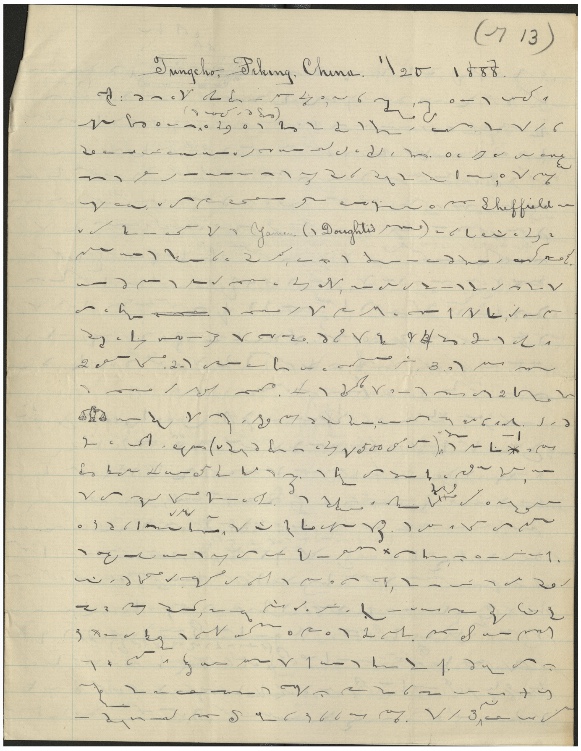

Here is the first page of a letter sent from China (Tongzhou, Beijing) to the US (Trenton, NJ) by a missionary in 1888. The missionary’s name is James Ingram (1858-1934). My colleagues in China are very interested in what the letter says, but they cannot read the script.

(credit: Yale Divinity Library)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

October 18, 2022 @ 5:36 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and religion, Usage

After uttering that affirmation in response to Peter Grubtal's wish (here) that "the [Butkara] stupa doesn't get destroyed like many other Buddhist relics in that area" — thinking of the Taliban and Bamiyan — I worried that what I said may have been too Christian and Jewish. Upon reflection, however, I realized that nothing could be more ecumenical (in the broadest sense) than "Amen":

Amen (Hebrew: אָמֵן, ʾāmēn; Ancient Greek: ἀμήν, amḗn; Classical Syriac: ܐܡܝܢ, 'amīn; Arabic: آمين, ʾāmīn) is an Abrahamic declaration of affirmation which is first found in the Hebrew Bible, and subsequently found in the New Testament. It is used in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim practices as a concluding word, or as a response to a prayer. Common English translations of the word amen include "verily", "truly", "it is true", and "let it be so". It is also used colloquially, to express strong agreement.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink