Orthographic variation in a pair of poems by a Japanese Zen monk and his mistress

« previous post | next post »

From Bryan Van Norden:

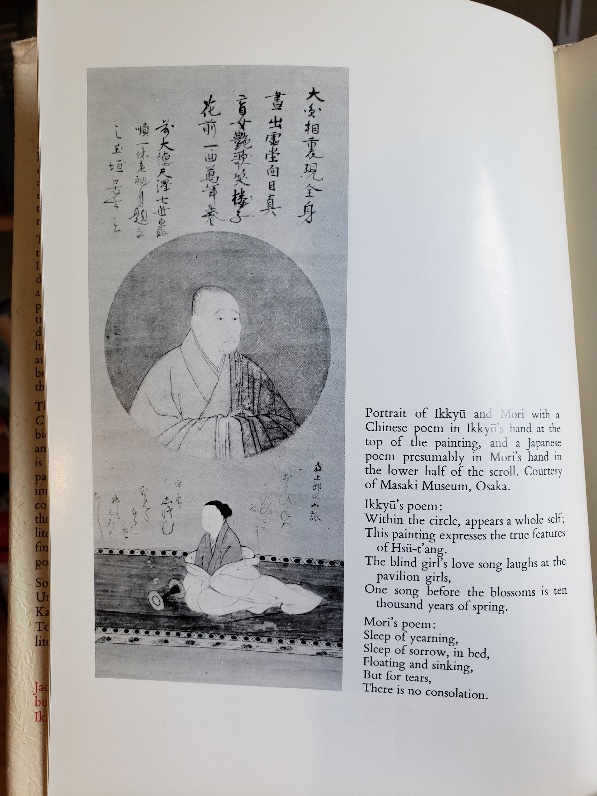

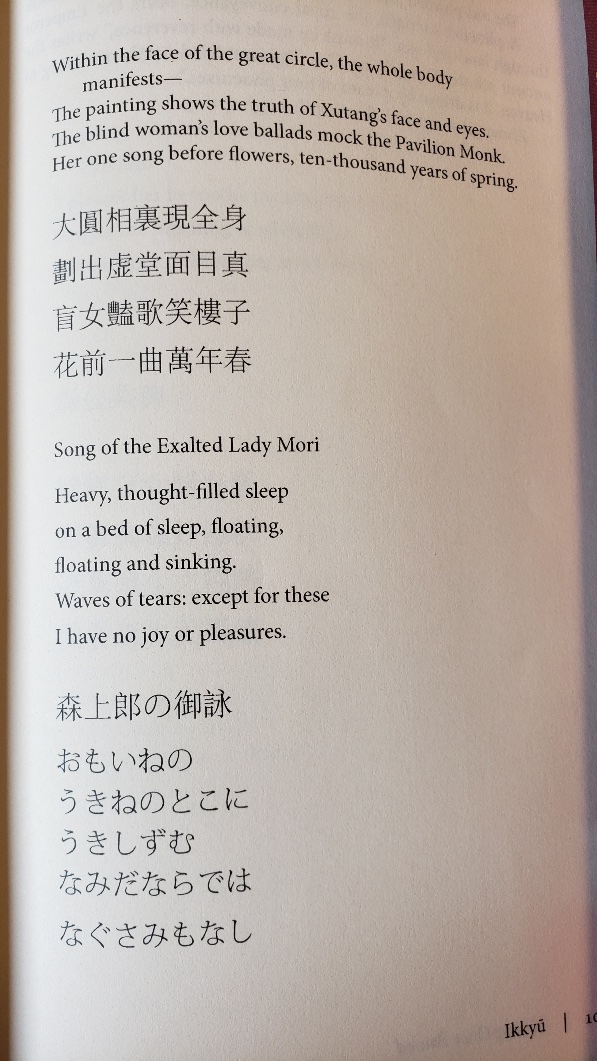

I found interesting these paired poems by the 15th-century Japanese Zen monk Ikkyū (1394-1481) and by his mistress, the blind singer Mori. He writes his poem in Classical Chinese, because he is a man, but her poem is in hiragana, because she is a woman. Below are photos of the original scroll, showing paintings of Ikkyū and Mori, from Arntzen's translation, and a more recent translation by Messer and Smith. I am researching Ikkyū for what will ultimately be a five-minute segment in my class lecture on Zen this week. I find that students have trouble appreciating what is at stake in the debate over metaphysical monism vs dualism. Ikkyū, a monk who frequented bars and brothels, shows one way of rejecting dualisms (like sacred vs profane, mind vs. body, monk vs. layperson).

From Sonja Arntzen, translator of the first set of translations above:

Your query is quite timely. I am just in the middle of revising and expanding Ikkyū and the Crazy Cloud Anthology (1987) for a reprint with Quirin Press. It is quite wonderful to be given the opportunity to go back to one’s first work and clean it up in the light of all the subsequent research that has been done by so many. I am just about to revise poem no. 144, which is the first poem in the Kyōūnshū to mention 楼子. I took it as Pavilion girl(s), the first time, meaning bar girls, but I missed the allusion to the Wudeng Huiyuan that Sarah Messer and Kidder Smith cite in their 2015 book (see the last paragraph below). Hirano also cites it in his Ikkyū Oshō Zenshū. As you well know, if you overlook an allusion in Chinese poetry or prose, you can miss the meaning badly, and that is the case here. Knowing now that 楼子 is the name for a monk who was enlightened by hearing a Pavilion girl sing a hurting love song, and that Ikkyū uses it as a nickname for himself, I would revise the third line of that poem to:

The blind girl’s love song mocks the Pavilion Monk,

In the light of the allusion, I was tempted to take a putative interpretation of 笑, “make the Pavilion Monk smile,” but have decided that Kidder’s translation is right for two reasons. One, Mori’s waka below speaks of insecurity and suffering. To have such a song make Ikkyū smile or laugh seems disjunctive. Secondly, his time with Mori overlapped with the Ōnin war (1467-1477) as Kidder points out, and the context of a second poem written around the time that employs the same line (see Messer and Smith, Having Once Paused, no. 531, p. 109) is at odds with smiling. In the poem’s introduction, Ikkyū states he wrote that poem out of grief over Mori refusing food when they were facing starvation.

You noted Mori’s poem being in kana because she is a woman. That is perfectly natural for the time. There were some Zen nuns in the medieval period who knew literary Chinese, but no woman in Mori’s position, that of a female entertainer. Interestingly, calligraphy experts are of the opinion that Ikkyū wrote the kana too. (Ikkyū bokuseki, Ikkyū Oshō zenshū: bekkan, p. 72) The sad tone of Mori’s poem may reflect the troubles of the time, but it is also good to remember that the discourse of waka is very much inflected by the ancient equivalent of the “blues.” There are almost no happy love poems in the waka tradition. By contrast, Ikkyū wrote a number of kanshi expressing joy over his relationship with Mori.

Looking at and thinking about this painting again, I realize that Ikkyū’s poetry and calligraphy on this portrait of the two of them probably secured funds for their survival. The painting is inscribed to a lay-follower of Ikkyū who was a resident of Sakai, the only safe place during the Ōnin war because, among many things, it was an armaments factory for all sides. Many Gozan monks sheltered in Sakai during that long war. Once he and Mori made it to Sakai, they would have gotten support.

So, those are my thoughts.

By the way, I am a fan of Having Once Paused (2015, by Sarah Messer and Kidder Smith). I had some communication with Kidder when he and Sarah were working on it and I really liked the idea of having all the allusions up front before getting to the poem. I like the way they make the poems accessible.

From Linda Chance:

The gendering of Japanese literature is a complex problem, but I would not express it as "Ikkyū writes in Classical Chinese because he is a man," nor "Shin writes in the vernacular because she is a woman." Then how would we explain Empress Kōmyō's kanbun, or Ariwara no Narihira's waka?

It is possible, of course, that the creator(s) of this kakejiku chose kanshi for Ikkyū and waka for Mori as part of a strategy of contrast. A monk's persona calls for kanbun; a blind performer's persona is mediated by kana. From what little I was able to find out about the painting, people assume that this is a portrait of Mori, and possibly even her calligraphy, but the kanshi is not confirmed as Ikkyū's because it does not appear in his collection.

Poking around online, I could not find a reproduction that was sufficiently clear for the hentaigana to be legible. But interestingly, four out of five of the images of the painting crop out Ikkyū's poem entirely. I believe they would crop out all of Mori's poem if it were not integrated into the background. As it is they tend to cut off both sides. Viewers now are intrigued by the portraits, but not so much by the inscriptions.

From Frank Chance:

To be honest, I don't like this sentence very much:

He writes his poem in Classical Chinese, because he is a man, but her poem is in hiragana, because she is a woman.

Could we not also say he wrote his sentence in Classical Chinese because he is a Zen monk, and a professional practitioner of sinitic culture, while she is a sex worker whose cultural expressions were expected to be in the vernacular? If she were a Zen monk (i.e., nun) she might well have written in Classical Chinese, but that was not her background. If he were a sex worker (and yes, there were male sex workers during his lifetime) he might well have written in the vernacular. Beware of gendering people[s language choices – the issues may be quite a bit more complex than just "Men wrote Chinese Women wrote Japanese."

From Robert Sharf:

I don't have much to add. Ikkyū's verse uses tropes typical of the 頂相 genre, in which one identifies the depicted abbot with the buddha. The use of terms like 圓相 (which can register as perfect form, empty circle, emptiness, awakening, etc.) and 全身 (here vaguely alluding to the body of the buddha), the allusion to the "truth" of face and eyes, etc., all suggest that Ikkyū has fully realized / embodied his intrinsic Buddhahood, and that this is captured / realized in the portrait itself. See T. Griffith Foulk and Robert H. Sharf, "On the Ritual Use of Ch'an Portraiture in Medieval China", Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, 7 (1993), 149-219.

Regardless of who wrote the two poems, the stark physical difference between the orthography of the poem by Ikkyū and the one by Mori is apparent even to someone who knows neither Sinographs nor kana (Japanese syllabary). That alone conveys something important to the reader / viewer.

Selected readings

- "More katakana, fewer kanji" (4/4/16)

- "Kanji amnesia of the week" (7/25/20)

- "Japanese survey on forgetting how to write kanji" (9/24/12)

(Thanks to Richard Lynn)

maidhc said,

April 3, 2021 @ 5:00 am

I am not much clued into the literature you are discussing here, But it seems to me that if the monastic life included having a mistress, it would be a lot more appealing.

findingsouth said,

April 4, 2021 @ 9:16 am

Notice the distinctive styles of the two poems. The monks's poem is a Tang poem with rhyme and a four-turn structure (起承轉合), whereas the mistress's follows a 5-7-5-7-7 mora structure. I agree with Frank Chance in that it depicts the contrasting lifestyles and cultural values between high and low classes, and between Chinese and native Japanese influence.

Josh R said,

April 4, 2021 @ 11:23 pm

"Professional practitioner of sinitic culture," is such a weird turn of phrase. I understand what Professor Chance is trying to say, and yet I feel this strong urge to disagree with it.

I study a classical Japanese sword art, and have viewed a number of historical documents. I wonder if these kinds of documents have been looked at from a linguistic perspective. The ones I've studied date to the mid-to-late 16th century, and orthographically they're all over the map. The schools founder writes in kanbun. His student copies part of those writings in kanbun, but then writes more in a kanji/hiragana mix. He also has licenses that utilize kanshi poetry. The same student also writes a collection of martial art poetry in tanka form that's primarily kana, with a sporadic kanji. A later mid-Edo period instructor writes commentary in kanbun, but it's highly idiosyncratic, and not easily readable as Chinese.

It's highly interesting from an amateur linguist's perspective, but I'm not sure how to place it in the wider Japanese literary context. Certainly by that time, the use of kanji vs kana or even kanbun vs vernacular does not appear to have a strong gender component.

Andrew (not the same one) said,

April 7, 2021 @ 5:51 am

maidhc: It's not clear to me whether his having a mistress was approved of by his order, but if it was, I'd suggest 'monk' is an inaccurate translation.

Ned said,

April 14, 2021 @ 7:43 am

Ikkyu was a monk, but also an enlightened Zen Master – so the usual criteria don't apply to him.