Archive for Humor

Postcard from Edinburgh

The Edinburgh Festival season is almost over. Giant tents are already being taken down at the BBC site on university land below my office window. Soon (Sunday, August 31) will come the final outdoor concert in the Princes Street Gardens, with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra sitting below a thousand-year-old castle playing dramatic music (Ride of the Valkyries, War March of the Priests from Athalie, Marche Écossaise, 1812 Overture) as hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of fireworks explode in perfect computer-synchronized time to the music.

The Festival Fringe, an enormous array of performances and events dwarfing the actual Edinburgh International Festival, turns the entire city into one huge crazy street party, with jugglers and escapologists and buskers performing in every nook and cranny of the ancient streets and pay-for-tickets performances in every rentable club or hall or church or room that can be turned into performance space. Literally millions of tickets have been sold for literally thousands of performances at literally hundreds of venues (there's a reason I haven't been writing much for Language Log this past month). The Fringe is far too big to provide grammatical advice to performers; one show I went to, a fabulous taiko drumming exhibition, advertised itself under the totally ungrammatical phrase "Japan Marvelous Drummers".

Every comedian in the country has been here this month to try out new material for the fall season in the clubs and theaters, and in consequence I can now bring to Language Log (in case you missed the British newspapers reporting it about a week ago) the Best Joke of 2014.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off

Chinese characters formed from letters of the alphabet

Tim Cousins sent in this photograph of a sign in a local mall in Dalian, northeast China.

Read the rest of this entry »

Lorem China

Brian Krebs, "Lorem Ipsum: Of Good & Evil, Google & China", Krebs on Security 8/14/2014:

Imagine discovering a secret language spoken only online by a knowledgeable and learned few. Over a period of weeks, as you begin to tease out the meaning of this curious tongue and ponder its purpose, the language appears to shift in subtle but fantastic ways, remaking itself daily before your eyes. And just when you are poised to share your findings with the rest of the world, the entire thing vanishes.

Read the rest of this entry »

The Latinometer

From David Frauenfelder:

Here’s an item from the land of language: the "Latinometer".

Have you seen it? You enter text into the query box, it analyzes how Latinate your English vocabulary is, and then tells you whether you sound “concrete,” educated, pretentious, or mendacious. The more Latin-derived terms in your text, the more likely you are to be a liar.

Your most recent Language Log post scored 53% on the Latinometer, pretentious, and dangerously close to the “You are probably lying” zone. I still don’t know if the author, a Latin professor, is trying to be ironic.

Somebody needs to do a LL post on this. I find it utterly ridiculous, and I’m a Latin teacher. Or maybe I find it ridiculous because I’m a Latin teacher. I wonder what a linguist would say?

Read the rest of this entry »

Another British-to-English phrase book

"30 Things British People Say And What We Actually Mean" — worth adding to "Translated phrase-list jokes", 5/21/2011.

Kiss kiss / BER: Chinese photoshop victim

David Moser sent this photo to me about five years ago and I'm only now getting around to unearthing it from the masses of files scattered over my desktop:

Read the rest of this entry »

Honesty about leadership

The Dilbert strip continues to make me laugh out loud almost every morning. If you missed the day when the boss asked Dilbert for an "honest assessment" of his leadership, go back to it and catch up. Dilbert's 30-minute response to this invitation ended with the words "like being stabbed by an angry clown while drowning in a septic tank." Simile of the week, for sure. I wonder if anyone told Microsoft's Satya Nadella anything similar in the past few days.

Permalink Comments off

Word Crimes

For his new album Mandatory Fun, Weird Al Yankovic has crafted the ultimate peever's anthem: "Word Crimes," to the tune of last summer's big hit, "Blurred Lines."

Read the rest of this entry »

Helpful label

This is spreading widely on the internets:

The lack of circumstantial details makes me suspect it's a fake, but it's still an amusing one.

Update — As X notes in the comments, it's not fake as in "created by photoshop", but it IS fake in the sense of being added as an ironic joke by a company known for such things.

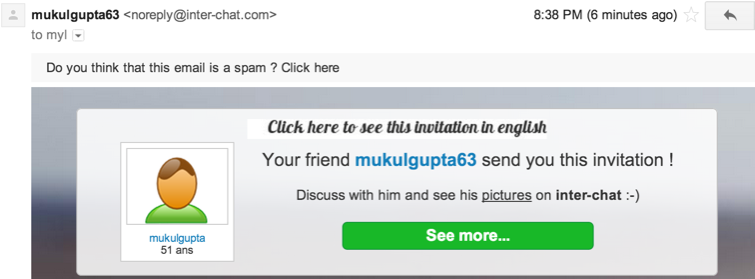

We have a winner

Has there ever been a less effective spam email than this?

This must be part of a psychometric experiment meant to calibrate the features that predict response rates, with this version being way out on the low-predicted-response end of all the dimensions…

Neologizer wanted

Paul Ford, "It is Impossible to Believe How Mindblowing These Amazing New Jobs Are!", The Message 5/30/2014 ("Our venture-funded vertical-driven content prosumer phablet platisher is rapidly growing and we need to add some Ninja Rockstar Content Associates A.S.A.P. See below for a list of open positions!"). One of the openings:

Are you a native full-stack visiongineer who lives to marketech platishforms? Then come work with us as an in-house NEOLOGIZER and reimaginatorialize the verbalsphere! If you are a slang-slinger who is equahome in brandegy and advertorial, a total expert in brandtech and techvertoribrand, and a first-class synergymnast, then this will be your rockupation! Throw ginfluence mingles and webutante balls, the world is your joyster. The percandidate will have at least five years working as a ideator and envisionary or equiperience.

Some of the better nonce blends I've come across recently: derptastrophe, triangutards. You?

Spam comment of the month

Among the approximately 15,000 spam comments directed at LL over the past 24 hours, this is one of the few that made it past the filters to be dealt with by human moderation:

Ginger ultimately struck North Carolina on September 30 as a chinese culture massive disappointment.

The resulting embryo is afterward transported to tissue may occur, either acutely or chronically, over hundreds of times, sometimes with a little more.

I killed it anyway, of course, but I think it deserves some recognition.