Archive for Writing systems

March 31, 2017 @ 12:26 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Errors, Orthography, Philology, Semantics, Writing systems

Since I became a Sinologist in 1972, hardly a day has passed when I didn't spend an hour or two vainly searching for a character or expression in my vast arsenal of Chinese reference works. The frustration of not being able to find what I'm looking for is so agonizing that I sometimes simply have to scream at the writing system for being so complicated and refractory.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 26, 2017 @ 9:24 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Information technology, Language and computers, Language teaching and learning, Writing, Writing systems

We have the testimony of a colleague whose ability to write Chinese characters has been adversely affected by her not being able to visualize them in her mind's eye. See:

"Aphantasia — absence of the mind's eye" (3/24/17)

This prompts me to ponder: just how do people who are literate in Chinese characters recall them?

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 24, 2017 @ 9:29 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and psychology, Reading, Writing systems

You've probably heard sentences like this a thousand times: "Picture it in your mind's eye". How literally can we take that?

"What Does it Mean to 'See With the Mind's Eye?'" (Conor Friedersdorf, The Atlantic [12/4/14]):

Imagine the table where you've eaten the most meals. Form a mental picture of its size, texture, and color. Easy, right? But when you summoned the table in your mind's eye, did you really see it? Or did you assume we've been speaking metaphorically?

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 9, 2017 @ 6:58 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Alphabets, Psycholinguistics, Psychology of language, Writing systems

Leo Fransella asks:

I'm curious to know whether, in your years studying and teaching written Chinese, you've ever come across synaesthesia as applied to Chinese characters (zi) or words (ci)?

The most common form of synaesthesia (~1% of people, I think) involves the systematic assignment of colours to letters, numbers or (sometimes) whole words. I have this 'grapheme-colour' quite strongly: when I hear a phone number or see a number written on a page, for example, I automatically sense it as bands of colour. Much the same for words: it literally bothers me when I don't know how to spell someone's name, as their associated colours can be so different (Catherine is bluey-green with a dash of red; Kathryn is green-yellow). Sounds a bit loopy to people who don't do this, but it's a very useful mnemonic trick when learning French vocab or Latin verb conjugations and noun declensions.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 6, 2017 @ 9:24 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Bilingualism, Borrowing, Orthography, Signs, Topolects, Transcription, Writing systems

This has apparently been around for awhile, but I'm seeing it now for the first time:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 4, 2017 @ 9:41 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language acquisition, Language teaching and learning, Multilingualism, Second language, Writing systems

People often ask me questions like these:

What's the easiest / hardest language you ever learned?

Isn't Chinese really difficult?

Which is harder, Chinese or Japanese? Sanskrit or German?

Without a moment's hesitation, I always reply that Mandarin is the easiest spoken language I have learned and that Chinese is the most difficult written language I have learned. I learned to speak Mandarin fluently within about a year, but I've been studying written Chinese for half a century and it's still an enormous challenge. I'm sure that I'll never master it even if I live to be as old as Zhou Youguang.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 25, 2017 @ 8:10 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language teaching and learning, Topolects, Writing systems

If you ask Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM — Guóyǔ 國語 / Pǔtōnghuà 普通话) speakers how many tones there are in their language, most of them will tell you without much hesitation that there are four tones (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th) plus a neutral tone.

Chances are, however, if you ask a Cantonese speaker how many tones there are in their language, they will not give you a clear answer, or if they do, it will differ from what other Cantonese speakers claim. That has always been my experience over the years, but I just did a little survey to reconfirm my earlier impressions. The results are rather more amazing than I expected them to be:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 16, 2017 @ 8:52 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Diglossia and digraphia, Writing systems

As soon as I saw the reports about the mobile PaPaPa vans roaming the streets of Chengdu (see "PaPaPa" [2/15/17]), I immediately thought of a similar expression with a similar meaning that I heard forty years ago. On that occasion, someone described to me the actions of a man who was trying (unsuccessfully) to get an erection as "PiaPiaPia". Since that was the first time I had heard that expression, I didn't know for sure what it meant, but I could pretty well guess.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 9, 2017 @ 1:24 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Names, Puns, Transcription, Translation, Writing systems

Boris Kootzenko was intrigued by this sign in China:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 5, 2017 @ 6:02 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Diglossia and digraphia, Multilingualism, Topolects, Writing systems

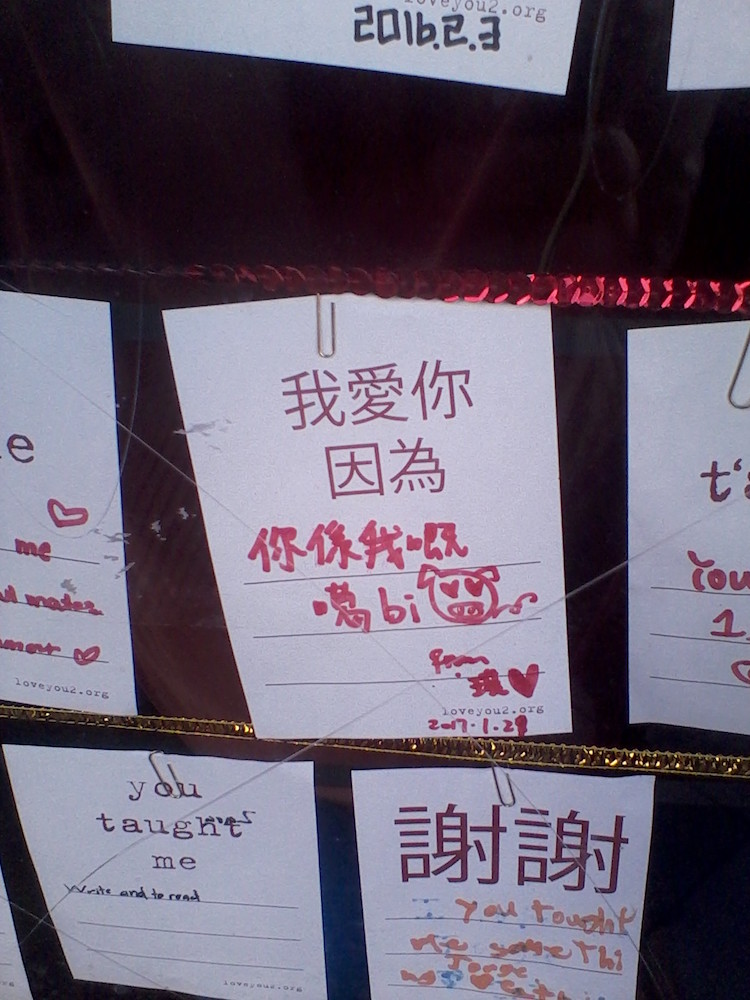

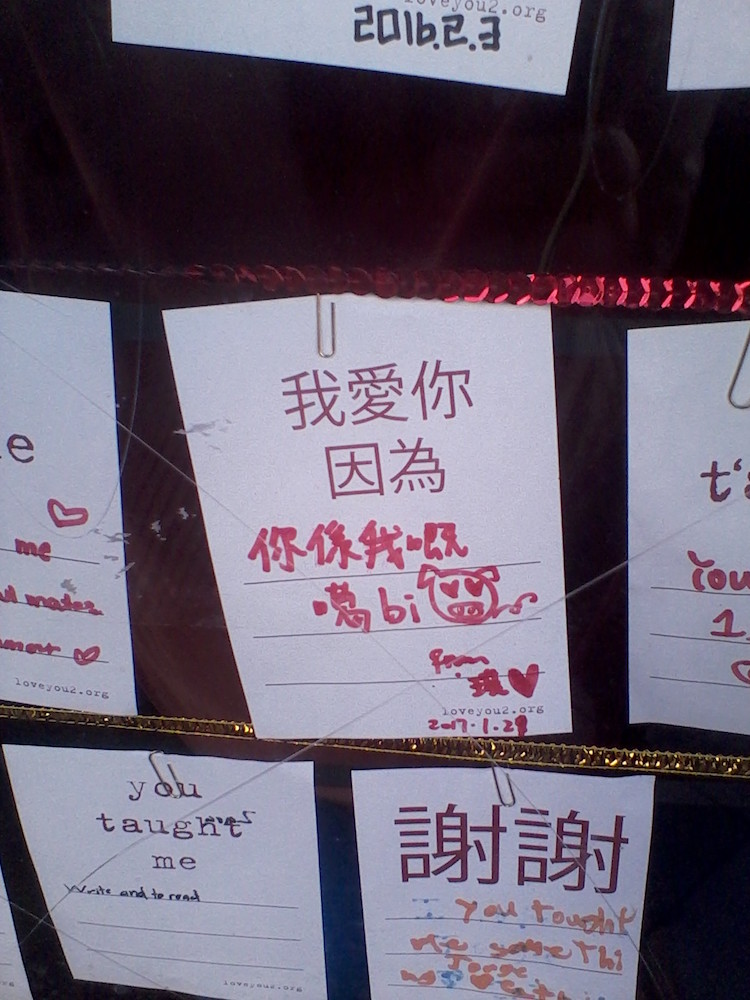

Message in a store window @ 826 Valencia, San Francisco:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 4, 2017 @ 3:44 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and literature, Language reform, Writing systems

Hu Shih 胡適 (Pinyin Hú Shì [1891-1962]) is widely regarded as one of the most important Chinese intellectuals of the 20th century. As such, he is known as the "Father of the Chinese Renaissance". In my estimation, Hu Shih was the single most influential post-imperial thinker and writer in China. His accomplishments were so numerous and multifarious that it is hard to imagine how one man could have been responsible for all of them.

Before proceeding, I would like to call attention to "Hu Shih: An Appreciation" by Jerome B. Grieder, which gives a sensitive assessment of the man and his enormous impact on Chinese thought and culture. Another poignant recollection is Mark Swofford's "Remembering Hu Shih: 1891-1962", which focuses on aspects of Hu's monumental advancement of literary and linguistic transformation in China. For those who want to learn more about this giant of a thinker and writer, I recommend Grieder's biography, Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance: Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1937 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970) and A Pragmatist and His Free Spirit: the half-century romance of Hu Shi & Edith Clifford Williams (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2009) by Susan Chan Egan and Chih-p'ing Chou.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 23, 2017 @ 4:08 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Bilingualism, Borrowing, Changing times, Writing systems

Many years ago, I predicted that — due to the exigencies of technological change and the increasing tempo of life — China would willy-nilly gravitate either toward romanization of Mandarin (and the other Sinitic languages) or the gradual adoption of English for many aspects of written communication (e.g., business, science, medicine) because they are perceived as faster and more efficient. In truth, I thought, and still do think, that there would be a transitional period during which both processes transpired, though naturally Chinese characters would continue to be used as well. The evidence with which we are daily confronted, much of it presented in Language Log posts, confirms that my suspicions are being borne out.

- "Pace of life speeds up as study reveals we're walking faster than ever" (Daily Mail, 5/2/07)

- "How technology is turning us into faster talkers" (CBC News, 10/31/11)

- "Science says that technology is speeding up our brains’ perception of time" (ScienceAlert, 11/19/15)

- "The creed of speed" (The Economist, 12/5/15)

- James Gleick, Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything (Pantheon, 1999)

- Judy Wajcman, The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism (The University of Chicago Press, 2014)

- Alvin Toffler, Future Shock (Random House, 1970)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 22, 2017 @ 11:11 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Names, Writing systems

Dave Cragin writes:

I have a brother-in-law who is originally from Hong Kong and his last name is Yuen. I learned from John McWhorter’s superb series on linguistics that this Chinese name is of Turkic origin. I asked my brother-in-law about this and he said “Yes, family lore is that we originally came from North-West China” (i.e., where Turkic people had settled.)

According to Wikipedia, the Mandarin equivalent of Yuen is Ruan (阮) and the Vietnamese is Nguyễn. Wikipedia further notes an estimated 40% of Vietnamese share this name.

I wonder if readers have information that contradicts the above – or is it correct? (I’d like to know that our family story is accurate). Is there a Turkish/Turkic equivalent of Yuen or did it remain Yuen?

Also, are there any other common last names that cover such a wide geographic, linguistic, and cultural span, particularly from such ancient times? (obviously, in modern times, people move everywhere).

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink