More old names for Singapore

« previous post | next post »

We have already studied an old name for Singapore on the back of an envelope dating to 1901:

- "An old name for Singapore" (9/6/16)

Now, Ruben de Jong, relying on the works of Dutch scholars, has discovered several others.

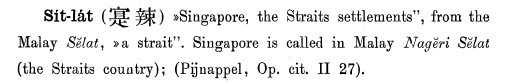

The first comes from Gustav Schlegel, ‘Chinese loanwords in the Malay language’, T’oung Pao 1.5 (1891): 391-405, 393.

Here's a screen shot of the relevant entry, viz. 寔辣:

The pronunciation Sít-lát is based on Hokkien, as in the previous blog post. However, we have not seen these specific characters in the previous post nor in the added example in the comments by Kirinputra.

Besides the historic predominance of Hokkien in Singapore and surrounding region (at least among the Chinese), finding this transcription in this particular topolect makes sense because Schlegel, like other Dutch Sinologists in the nineteenth century, mainly studied fāngyán 方言 like Hokkien and Hakka. They did so because these were the Sinitic languages spoken in the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia), and their training as Sinologists was based on a future career as civil servants (interpreters and translators) in the colony (for more, see the excellent recent PhD dissertation of Pieter Nicolaas Kuiper on the topic).

Schlegel cites a certain Pijnappel, i.e., his Malay-Dutch dictionary, and from this work Schlegel might have gotten some of his information: e.g., Schlegel connects the Hokkien name to the Malay word for “strait” (as we did in the previous post) .

Besides Pijnappel's dictionary, Schlegel’s own multivolume Dutch-Hokkien dictionary (i.e., in Zhangzhou topolect, literary reading) might also be consulted. This work has been partly digitized, although the volume most likely to contain the name for Singapore is missing (see here).

In the name 寔辣, 寔 is a variant of shí 實 / 实 ("real; actual; solid; true"). See this zdic entry.

The second item comes from P.A. van de Stadt, Hakka-woordenboek (Batavia: Landsdrukkerij, 1912). As the title indicates, this is a dictionary for Hakka and was based on the topolect as spoken in Bangka and Belitung, Indonesia.

Here is p. 409:

It shows two names for Singapore. Once again, the first character of the second name (Sit lát), 息 ("interest; rest; breath; news"), has not been mentioned before in our discussions on this subject. A nice aside: the Dutch text in the right-hand column informs the reader that often similar sounding characters are used.

The third name comes from J. J. C. Francken and C. F. M. de Grijs, Chineesch-Hollandsch woordenboek van het Emoi dialekt (Batavia: Landsdrukkerij, 1882). In spite of its title indicating that this is a dictionary for the Emoi (Amoy) dialect, this work – like that of Schlegel – is also in part based on Zhangzhou Hokkien (cf. p. 404 of the PhD diss. by Kuiper, mentioned above).

Here is p. 537:

We see the same character as in Van de Stadt’s work, but with a mouth radical added on the left, 口+息.

The upshot of all this is that, in studying the Sinitic transcriptions of foreign names, we must take into account topolectal variation and the secondary nature of graphic representation: what matters most are the sounds, not the shapes.

AntC said,

October 19, 2016 @ 3:57 pm

Thank you Victor, again fascinating.

So as with pre-sinitic names for Taiwan (Taoyan), it seems to be the European colonists who captured local fangyan pronounciations/non-Mandarin topolects.

what matters most are the sounds, not the shapes. If they were capturing in an alphabetic script, you'd call it transliteration. Is there a term for 'phonetic spelling' using sinitic characters?

Is this capture of the phonetics a data point for historical sound change? But it can only go so far back as the European exploration period (or Arab traders before that?)

Victor Mair said,

October 19, 2016 @ 5:34 pm

@AntC

I only consider it transliteration when going from one alphabet (with letters) to another. In all other cases, it's safest to call the writing down of sounds or the transfer of sounds from one writing system to another transcription.

People have been borrowing / recording words from other groups / languages for as long as there has been writing. In all such cases we can use these transcriptions as "data point[s] for historical sound change".

The problem with a morphosyllabic or logographic writing system like Chinese is that we are not always able to reconstruct / determine with assurance (especially the further back we go in time) the precise sound that the individual characters represented. That's why it's so important to compare Chinese records with records written in languages that use phonetic scripts (e.g., Sanskrit, Arabic, German, Armenian, etc.) whenever possible.

Leonard van der Kuijp said,

October 20, 2016 @ 11:49 am

Yes, indeed, thank YOU Victor..always fascinating what you manage to excavate!

KIRINPUTRA said,

October 21, 2016 @ 7:37 pm

Interesting!

Something else I notice about HAKKA-WOORDENBOEK from the snapshot is that they used the "POJ-type" (Péh-ōe-jī-type) tone markers, not the set used in Hakka Wikipedia and AFAIK the version(s) of the Hakka Bible that survived into the 21st century.

Most times I'd say usage trumps all, but the "Hakka Bible" set of tone markers lacks a viable marker for the 下去 tone. This is a problem for Hoiliuk (海陸) dialects since they have that tone. Now I think Bangka-Belitung Hakka is Hoiliuk-derived. I wonder if they "lost" that tone, or if they had/have it but van de Stadt just didn't deal with it.

David Marjanović said,

October 23, 2016 @ 6:54 pm

I've even seen "transliteration" used with a very narrow meaning: to transcribe from one alphabet to another obeying a 1 : 1 correspondence (which usually requires unusual diacritics). Transcription is in any case the more general term.

AntC said,

October 24, 2016 @ 7:03 pm

@Victor (and @David M) it's safest to call the writing down of sounds or the transfer of sounds from one writing system to another transcription.

Thank you. Yes, my bad.