Confessions of an Ex-Hokkien Creationist

« previous post | next post »

[This, a guest post by Lañitri Kirinputra, is the fourth and last in a series of four posts on Hokkien and related Southern Min / Minnan language issues. The first was "Eurasian eureka" (9/12/16), the second was "Hokkien in Singapore" (9/16/16), and the third was "Hoklo" (9/18/16).]

Hokkien1 Creationism

The romanization debate was hot around 2005-06. Should we go on using the one- and-a-half-century-old Pe̍h-ōe-jī (“POJ”) scheme? Or should we use a modified flavor of POJ? Or should we use another more Pinyin-like scheme? The POJ camp was going on and on day after day about how POJ had history, literature, yada yada yada.

“Brothers and sisters,” I said one day on a listserv, “let's face it. Only Presbyterians used POJ. POJ was small-time. Written Taiwanese was small-time. We ain't inheriting Written Taiwanese. Ain't nothing to inherit. We're creating Written Taiwanese.”

A tree falling in the forest. Nobody paid me no mind. Over the years, though, it came back to haunt me: how wrong I was that day. Not just me, but two generations of “Hokkien Creationists”, most of them too mild or confused to come out and say what they all believed, which was that there had been no Written Hokkien before them — or, if there was, it was invalid or incomplete or both.

You know about Pe̍h-ōe-jī

In case you don't, Pe̍h-ōe-jī (白話字) is a Hokkien romanization scheme2 — the only one that's ever caught on at scale as a means of communication. By the mid 20th century, it was used by probably over 100,000 Hoklophones on both sides of the Taiwan Strait and around the Straits of Malacca. It faded in the second half of the 20th century with the rise of nationalistic compulsory education pretty much everywhere. Republic of China (“ROC”) offcials on Taiwan went the extra mile, banning the publication of POJ materials and raiding churches to confiscate existing publications in POJ.

The Taiwanese Creationists of the last 30-some years obviously knew about POJ. Many or most of us knew it too. The project to re-invent Written Taiwanese was no knock on POJ. It just kind of went without being said: no matter the merits of POJ, Hokkien had to at least have an alternate form that was based on Hàn-jī (漢字, Jp. Kanji, hereinafter “Hanji”). “A language like Hokkien” couldn't live on romanization alone. Till about 2005, there was a loud, proud POJ-only camp that argued against this idea, but let's put this issue aside for now. What I want to talk about is the Hanji-based Written Hokkien convention of pre-ROC-on-Taiwan times.

What people think they know about pre-ROC Hanji-based Hokkien

Anybody who sets out to learn or learn about Hanji-based Hokkien these days will get the impression that pre-ROC Hanji-based Hokkien was, at best:

- Utterly unstandardized. To each man his own version. An unholy mess. Internally inconsistent.

- Largely made up of sound-only Hanji, or what the Japanese call ateji (当て字): Hanji employed for their sound value, with no regard to their “underlying meaning”.

- Well-represented in the experimental mess that was Hanji-based Hokkien in the 1980s and 90s.

- Reasonably well-represented in a series of 19th and 20th century dictionaries and rimebooks that allow us to access a cleaned-up version of pre-ROC Hanji Hokkien without having to look at any actual writings.

- Reasonably well-accounted for by the scholars of the late 20th century, who used the pre-ROC orthography as a starting point for the Neo-Hokkien they were creating, only replacing the parts that were unworkable.

This is what I used to think too, pretty much, before I found Tō͘ Kiàn-hong's (杜建坊) essays. From there I looked for and found dozens of pre-ROC Hokkien publications that had been uploaded to the internet. It was a rude awakening. Pre-ROC Hokkien was surprisingly consistent. It spanned 400 years. The later stuff showed a level of orthographic polish and de facto standardization comparable to the Cantonese of today. Most of the late 20th century orthographic mess was not to be found in the pre-ROC publications. (Most of the mess that the Taiwanese Creationist scholars and writers claimed to be cleaning up had in fact been introduced by their own selves!) In turn, the conventions in the pre-ROC publications were only partly represented in the dictionaries and rimebooks of their time. And while scholars of the last 30-some years often cited “popular” (民間 bîn-kan) usage, it turned out what they meant by “popular” most times was in fact select dictionaries and rimebooks instead of popular … usage.

The Lâm-koán Play Scripts

The oldest piece of Written Hokkien known to modern man is a 1566 edition of Nāi-kèng-kì (荔鏡記, Tale of the Lychee Mirror). The full title of this edition indicates it was a “re-publication” (重刊 têng-khan), so we know the tradition goes back even further than that. How much further is hard to say. As far as orthography goes, Nāi-kèng-kì falls within a genre of plays called Lâm-koán-hì (南管戲, “LKH”) because they're set to Lâm-koán music. The internal consistency of LKH orthography — and the consistency of the 1566 Nāi-kèng-kì orthography with the centuries of LKH orthography that came after — suggests that LKH-style Hokkien orthography was old hat by 1566.

LKH scripts were written3 in a high vernacular register4 of the dialect of inner city Choân-chiu (泉州, Mand. Quánzhōu), with lots of Classical Chinese elements thrown in. Nāi-kèng-kì also had a lot of lines written in Teochew,5 as well as some lines — belonging to the mandarins, of course — in a hybrid of Mandarin and Hokkien or Teochew.

LKH scripts were targeted at actors and backstage personnel. They were never meant for mass consumption. Still, for a written language to debut at such a non-mainstream venue might be par for the course. Timing-wise, LKH Hokkien could be seen as part of a wave of vernacular writing that came up in the Sinosphere mid-millennium, maybe as a trickle-down response to a greater emphasis placed on vernacular writing by the Mongols when they ruled China.

The Age of the Koa-á-chheh

Koa-á-chheh (歌仔冊, “KAC”) are a type of rhyming storybook, typically seven or eight dense pages, sometimes a lot longer or a lot shorter.6 KAC started with Siù-siōng Ông Chhau-niû sin-koa (繡像王抄娘新歌) in 1826. KAC published in Amoy and Shanghai (for the Taiwan Strait market, no doubt) tended to be re-tellings of well-known epics and folk tales, but Taiwanese KAC writers in the Japanese era branched off into all genres of fiction and even non-fiction.

KAC peaked as a cultural phenomenon in Taiwan from the 1920s to about 1960. At one point KAC were probably meant to be read aloud by a raconteur to an audience. By the 1920s and 30s in Taiwan they were being mass-marketed and sold direct to “the man on the street” for him to read through on his own. Two changes made this possible. First, new technologies made it cheaper to print things. Second, basic education in Classical Chinese (漢文) became way more widespread under Japanese rule — and for any fluent Hokkien speaker with a working knowledge of Classical Chinese based on Hokkien readings, KAC is an easy hack.

Pre-ROC-style Hokkien as a society-wide phenomenon

Orthographically speaking, LKH and KAC were not discrete phenomena with no relation to society. KAC clearly inherited the orthographic conventions of LKH — deliberately, in fact: a lot of early KAC were re-makes and extensions of Nāi-kèng-kì. In turn, mid-20th-century Taiwanese pop lyrics were inherited from KAC, at least sometimes. The orthography of Hokkien-language place names in Taiwan, southern Hokkien (福建, Mand. Fújiàn), and Southeast Asia also operated on the same logic. It was really one orthography, one unstandardized convention. To this we could add shop signs and menus, to some extent.

How does Creationist Hokkien differ from pre-ROC Hokkien, orthography-wise?

The tree I'm trying to bark up here is the threshold question of why or how is it okay to do away with and replace a long-running orthography (while pretending to uphold it). I'm not trying to argue the “merits” of one approach over the other, as if Hokkien had never had a Hanji-based orthography before and we were interviewing candidates. At the same time, though, the nature of the Creationist orthography tells us a lot about why Creationists felt the need to re-do Hokkien orthography in the first place.

Taking the ROC MOE recommendations as representative of Creationist orthography and LKH and KAC writing as representative of pre-ROC orthography, the main difference is that pre-ROC writers were Hokkien-centric. They used Hanji (and locally created Hanji-oids) to express Hokkien in writing. The life and times of Hanji in Classical Chinese or other languages was secondary. Creationists, on the other hand, are subconsciously Zhōngwén7-centric. For them, the central question of how to write any given morpheme is, “Which Zhōngwén morpheme is this cognate to?” They tend to not ask whether the morpheme has a “Zhōngwén” cognate — they have a religious8 belief that every Hokkien morpheme does, in practice, unless it's a modern non-Sinitic loan.

As a group, LKH writers — KAC writers, not so much — showed tremendous sophistication not only in recognizing Hokkien-Classical Chinese cognate pairs, but in “laying off” false cognate pairs. Creationists, though, flock to false cognate pairs because they believe a false pair is better than no pair at all.

Pre-ROC writers made heavy use of sound-only Hanji (ateji). Creationists are allergic to sound-only Hanji. Their main complaint about pre-ROC Hanji-based Hokkien is that it uses too many sound-only Hanji. It's true that sound-only Hanji water down the graph-to-meaning relationship of Hanji… Pre-ROC writers didn't care too much, but Creationists strongly object.

Pre-ROC writers also made heavy use of meaning-only Hanji, analogous to Japanese kunyomi (訓読み). Creationists are also allergic to most meaning-only Hanji. Their objection seems to be that meaning-only Hanji water down the graph-to-sound relationship of Hanji. This is true if we look at things Zhōngwén-centrically or Middle Chinese-centrically, but that's exactly how most Creationists look at things, subconsciously.

Creationists' rejection of both sound-only and meaning-only Hanji at the same time brings to mind the Mandarin saying Yòu yào mǎér pǎo, yòu yào mǎér bù chī cǎo (又 要馬儿跑、又要馬儿不吃草): wanting the horse to run, run, run but never graze. You can't have it both ways. If a Hokkien morpheme doesn't have a Chinese cognate, assuming we can't coin new Hanji-oids at will, we then have to use either a sound-only Hanji or a meaning-only Hanji. The only alternative would be to inject non-Hanji elements like POJ into the text — another idea that a lot of Creationists recoil from.

Cornered by their own prejudices, Creationists typically respond by making sure every Hokkien morpheme has a Chinese cognate! If a solid cognate can't be found, they just take the most likely one — no matter how unlikely — and make believe it's The One.

Creationists hate meaning-only Hanji because of their cognancy fetish. Every meaning-only Hanji is like a white flag saying, “Hey, look, they couldn't find a Chinese cognate for my morpheme.”

Another dimension of difference is that some Creationists expect to be able to read Hokkien fluently based on their ability to read Mandarin fluently. This is based on the old belief that Hokkien, Mandarin, etc. are not really different languages. For this reason, paradoxically, meaning-only Hanji based on Mandarin — not the usual Classical Chinese — were introduced.

For example, the Creationists brought in 才 from Mandarin to write Hokkien chiah (meaning "only if; just now", etc.). In LKH and KAC, this word was written with the sound-only Hanji 即 over 95% of the time — none of the famous pre-ROC lack of uniformity. What's more, 才 itself was not only a meaning-only Hanji, but, internally to Mandarin, it was also a sound-only Hanji. All this was forgiven in order to make Hokkien more Mandophone-friendly.

Again, the Creationists brought in 的 from Mandarin to write Hokkien possessive marker and nominalizer ê, a word that was consistently written either 个 or 兮 pre-ROC. Internally to Mandarin, 的 was also a sound-only Hanji.

To zoom back out a little, another pattern of difference between pre-ROC orthography and Creationist orthography is that the former favors simpler, lighter, more common Hanji while the latter favors complicated, stroke-heavy, rarer Hanji. The pre-ROC orthography was like Japanese and Classical Chinese in tending to use light, simple Hanji for function words. The Creationist orthography is like Mandarin or Cantonese orthography, with dense, convoluted Hanji sometimes being assigned to the most common, most unassuming function words.

It's an ROC thing

By and large, Creationist Taiwanese is clearly a creature of the ROC. And the way it emerged — as if it was the frst real Hanji-based Hokkien orthography ever, as if there had been no Hokkien orthography before ROC times — is the classic pattern in the modern ROC-on-Taiwan where everything that came before Chiang Kai-shek is ignored, and the phrase “… in the history of Taiwan” redirects to “… in the history of Taiwan post-1949”.

Ironic, if we consider the political views of most Creationists.

“Correcting” popular usage

In 17 years of learning and using Hokkien the Creationist way (but with a wicked linguist's twist), I came across these recurring “errors” that cropped up when the general public wrote in Hokkien. It turns out that some of these “errors” were just instances where pre-ROC Hokkien had something written one way, and the Creationists just decided it should be written a different way.

For example, to this day the general public tends to write gín-ná (meaning CHILD) as 囝仔. The scholars say it should be 囡仔. Their disciples tend to correct 囝仔 as if it was a garden variety error. In fact, 囝仔 goes back at least as far as the earliest KAC. It's the use of 囡仔 that's questionable on several fronts. It reflects not some deeper linguistic truth but rather an obsessive-compulsive need to bring Written Hokkien in line with the footnotes of famous essays and dictionaries scribed in Hángzhōu and points north.

KAC and pre-ROC-style Written Hokkien nearly went extinct in the 1960s, as the ROC labored to replace Taiwanese cultures and languages with ROC culture and Mandarin. It's amazing that pre-ROC usages like 囝仔 are still in the collective memory to this day.

What conspiracy?

For the record, I kind of doubt any scholar of Hokkien would've collaborated on the eclipse of pre-ROC Written Hokkien on purpose. Taiwanese people born in the 1940s and 50s were the first generation of people anywhere to get clusterfucked full-strength by the ROC propaganda machine from the first day of school on. They were misled themselves from the start. The other side of the strait was not good times either. Let's leave it at that.

Meanwhile, the age-old tendency of landlord-scholars to only cite other landlord- scholars probably goes a long way toward explaining the “popular usage” bait-and- switch described earlier.

Why does any of this matter?

So now the ROC state is sponsoring one Creationist orthography while the pre-ROC orthography that got us from the mid 16th to the mid 20th century and was used to name cities and rivers is cast away while we make believe that all its worthwhile elements have already been incorporated into the Creationist orthography. Why does this matter? As I see it —

First, the aesthetic downgrade. Admittedly subjective.

Second, the Creationist orthography is in effect seeded with thousands of false clues regarding the linguistic history of Hokkien.

Third, the pre-ROC orthography is Hokkien-centric. The Creationist one is not.

Fourth, the sound-only Hanji used in the pre-ROC orthography are essentially Hokkien manyōgana (万葉仮名) — the precursor to hiragana. An aesthetically Hanji-compatible alphabet or syllabary is exactly what Hanji-based Written Hokkien needs going forward. The Creationist orthography moves away from this toward a Middle Chinese-centric phonological paradigm.

Fifth, most languages are written the same way they were written last year, and the year before that, and so on. Why should Hokkien be the exception? What justifies a reset? This could be a non-rhetorical question.

For anybody that's just interested in Hokkien orthography for its own sake, I say look where you may not have known to look.9

Notes

- Come, let's use “Hokkien” and “Taiwanese” interchangeably here.

- Near-identical schemes also called “Pe̍h-ōe-jī” or the equivalent were introduced for Teochew, Hakka, and other languages too, to be precise.

- LKH is alive as a performance art, but no new plays have come out in over 100 years.

- This might sound like an oxymoron to many modern minds. The high register of modern Hokkien (or Cantonese) is non-vernacular, and the vernacular register is low, all of this almost “by definition”. A decent modern example of a high vernacular might be the language of Vietnamese pop. It's worth keeping in mind that Hokkien and Vietnamese were “the same kind of animal” for much of their history. Many of the “obvious” differences are artifacts of the last 120 years or so of politicking.

- Hokkien and Teochew may not have been as distinct from each other 450 years ago as they are today, either in terms of “raw” mutual intelligibility or in terms of social perception.

- So how are koa-á-chheh (歌仔冊) and koa-á-hì (歌仔戲) related? Short answer: they're not.

- What is Zhōngwén (中文) anyway? Apparently: a combination of Modern Standard Chinese (Mandarin), Classical Chinese, and all languages past or present spoken within the borders of modern China that either use(d) a Hanji-based orthography or have (had) a diglossic relationship with the Hanji-based written form of some other language. This concept didn't “crystallize” till after the rise of Zhōnghuá (中華) ideology in the late 19th or early 20th century. Zhōngwén is usually translated as “Chinese” in English, but sometimes it's translated as “Mandarin” because that's its core element. “Zhōngwén” is where the “zh” in all them language codes comes from, by the way.

- This is more than a figure of speech. The core of Hoklophone religious belief is patrilineal ancestor worship. Almost all Hoklophones trace their patri-lineage back to some mythic once-upon-a-time in the Chinese heartland. No surprise that so many Hoklophones try to trace all or almost all the words of their language back to the same place.

- You can read a good many koa-á-chheh here: http://cdm.lib.ntu.edu.tw/cdm/

search/collection/kua-a-tsheh

You can get to know the pre-ROC Hokkien orthography word by word or Hanji by Hanji at my Tumblr: http://sui.tawa.asia/

Illustrations

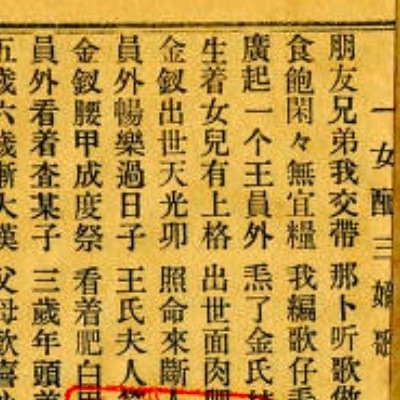

A page of a KAC.

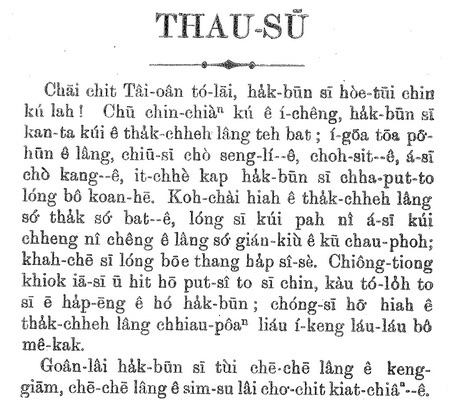

A page of POJ.

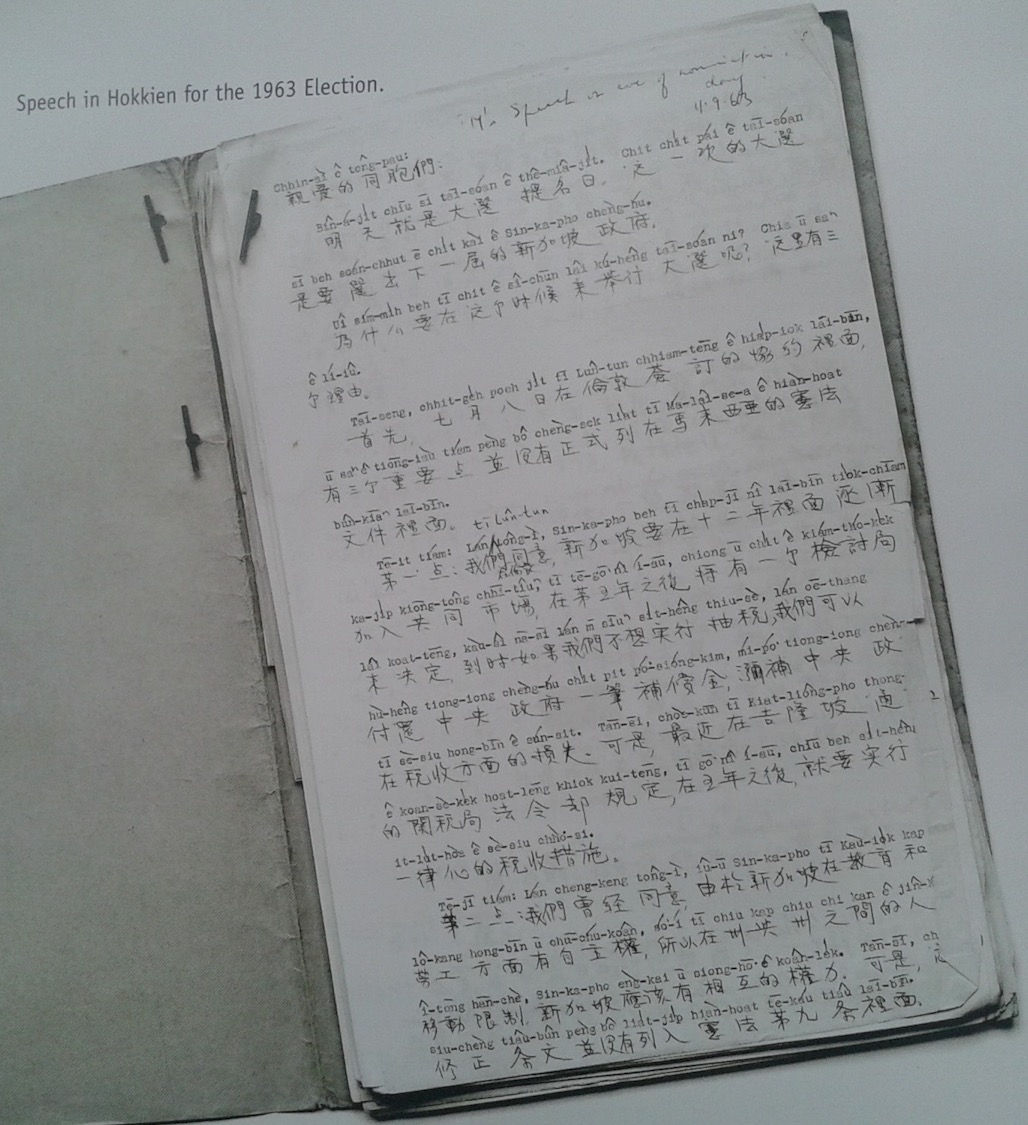

Lee Kuan Yew's notes for one of his early speeches

in Hokkien, in POJ with Mandarin glosses.

Bathrobe said,

September 21, 2016 @ 12:07 am

This is absolutely fascinating! Language is such a political animal…

flow said,

September 21, 2016 @ 5:52 am

Thank you for giving us such a dense, rich and colorful essay. It is a joy to read, both for the story it tells as well as its language alone. To be sure, a passage like this:

"[…] [T]he Creationists brought in 才 from Mandarin to write Hokkien chiah (meaning "only if; just now", etc.). In LKH and KAC, this word was written with the sound-only Hanji 即 over 95% of the time — none of the famous pre-ROC lack of uniformity. What's more, 才 itself was not only a meaning-only Hanji, but, internally to Mandarin, it was also a sound-only Hanji."

is so dense, it takes a rather generous pinch of circumstantial knowledge to fully digest, or make sense of at all (and I'm not talking about the acronyms—LKH, KAC, ROC—here). I cannot remember having read any rundown of Hokkien / Taiwanese (as we called it back then) / Ho(k)lo(u) linguistic history before that was as much fun and as informative as this one. No doubt the KMT's 'going the extra mile' (!) was effective as far as I'm concerned.

Incidentally, I used to own a whole slew of 1980s, 90s books about the Hokkien Orthographic Question, writing and orthography being of great interest to me. I find those books described very well in the above; they must have come out of what is here dubbed the Creationist movement. Thoroughly puzzling, may I say, but now I know better why:

"The Creationist orthography is like Mandarin or Cantonese orthography, with dense, convoluted Hanji sometimes being assigned to the most common, most unassuming function words."

Insisting on convoluted Hanji in place of simpler, allegedly 'merely vernacular' forms is, I feel, something typical for the KMT-ROC educational system (ah those days at the 國語日報). The first two offenders in this respect that come to my mind are 才 and 只, and sure enough, turning to my database of CJK variants and usages (which is mainly distilled from data produced by the Unicode IICORE team), I find among those ./. 16.000 characters the following:

才CJKTHM 財JKTHM 纔T 财C 㒲

只CJKTHM 祇cJKTHM 隻JKTHM 衹T 秖

Observe that the letters following each glyph stand for mainland ( C)hina, (J)apan, the (K)oreas, (T)aiwan, (H)ong Kong and (M)acau, meaning that writing 纔 for 才 and 衹 for 只 has **only** been brought forward by the Taiwanese (i.e. ROC) emissaries to the IICORE meetings. People, if you only learned Mandarin and grappled with 纔 for that small, humble word, 'only', this is what you get when a culture gets oppressively hypercorrective. In the same vein, the most recent official recommendations by the ROC MOE concerning what printed characters should exactly look like are full with stupid hypercorrected forms (a.k.a. as 'Songti') that are, properly speaking, calligraphic blunders small and large.

I only say that to bring out my point that while I'm all *for* preserving the cultural achievements of the past—frankly, a mainstream that mistakes linguistic (and typograhic, and orthographic) peevery for an informed and embracing view on traditional values is not helpful at all.

"An aesthetically Hanji-compatible alphabet or syllabary is exactly what Hanji-based Written Hokkien needs going forward."

I'd be excited to see something along *those* lines! I once developed a Hangeul-based orthography for Mandarin, works like a charm both functionally and aesthetically, if I may so say myself. Of course, in these days of smartphones and computers, you'd restrict yourself to transmitting transcripts and images until such day that the Unicode consortium publishes an update to their standard to include your efforts. But why not at least try?

Simon P said,

September 21, 2016 @ 6:32 am

I don't speak a work of Hokkien, but as an enthusiast of Cantonese and supporter of plurilingualism, it frustrates me to no end that Taiwan, the only place where I feel we have a true hope of a true, literary, socially accepted non-Mandarin written Chinese language, cannot seem to make up its mind on how the orthography should work.

Victor Mair said,

September 21, 2016 @ 6:35 am

@Bathrobe, @flow, @Simon P

Amen! Amen! Amen!

Victor Mair said,

September 21, 2016 @ 6:35 am

As someone who relied heavily on Guóyǔ rìbào 國語日報 (Mandarin Daily News) for learning to read Chinese — see inter alia "The future of Chinese language learning is now" (4/5/14) and "How to learn to read Chinese" (5/25/08) — and whose mainland teachers from Taiwan inculcated the same precepts about writing, I always compulsively wrote 纔 instead of 才 for "cái" ("only; just"), 衹 instead of 只 for "zhi" ("only; merely"), 臺 instead of 台 for "tái" ("tower; lookout; stage; platform; terrace;" transcription for the first syllable of "Taiwan"), etc., and thought that to do otherwise was wrong. Little did I know!

Think of all the tens of thousands of unnecessary strokes I labored over! 纔纔纔纔纔纔纔…, 衹衹衹衹衹衹衹…, 臺臺臺臺臺臺臺………..! — when I could have been doing something more interesting and useful, not to say fun.

Janet Williams said,

September 21, 2016 @ 7:08 am

Dear Victor,

I would like to add this word to your list – 憂鬱 – won't you feel melancholic when counting the number of strokes in 鬱? I must say I used to feel so thrilled when I managed to write every single stroke of this character perfectly. I think I can still write it well.

In exam, we had to.write 'neatly', and every stroke counts. At times when I forgot the strokes, I would pretend I wrote in cursive form, missing a few strokes here and there, and hope that the teacher wouldn't find out. Of course sometimes I could get away with this, but most of the time teachers wouldn't accept a 'half-baked' character.

I feel 鬱 is easier to write than 龜, which I struggled a lot with symmetry, in primary school.

Not sure how 憂鬱 has now become 忧郁 – they look completely different.

JS said,

September 21, 2016 @ 9:23 am

Awesome post, awesome tumblr, awesome first footnote. Thanks!!

Victor Mair said,

September 21, 2016 @ 10:10 am

Way back in the early 90s (and long before), I recognized the extraordinary importance of this play — Nāi-kèng-kì (荔鏡記, Tale of the Lychee Mirror) (1566) — and included an excerpt (translated by yours truly) with a long, long footnote, in The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature (1994), pp. 1295-1298.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 21, 2016 @ 2:29 pm

One possible answer to possibly-non-rhetorical question five, is that there probably have been loosely parallel situations elsewhere, even leaving aside the cases of languages which just switched writing system en masse (like Turkish). One that comes to mind (although I'm sure there are others) is Lithuanian. The current standard orthography has been largely stable since the early 20th century, but printed books in Lithuanian go back four or five centuries before that, with earlier orthography somewhat irregular but generally converging around conventions that the present orthography significantly departs from. (The earlier orthography was often similar to Polish, whereas the modern one goes out of its way to reject Polish-style usages and typically follows Czech orthography, which systematically differs from Polish in the details of how to render a reasonably similar underlying language in the Latin alphabet.)

Reasons for the Lithuanian situation as I understand it (draw your own parallels to Hokkien): 1) the older orthographic tradition was long-running but shallowly-rooted in the community, in that Lithuanian was predominantly an oral "peasant language," with government administration, high culture, and most other things that would tend to be done in writing in areas dominated by Lithuanian-speakers being typically carried out in other higher-status languages which peasant offspring ambitious of professional advancement had to master; 2) there was a discontinuity in the older tradition in the generation before the new orthography was codified because an oppressive government (in this case Czarist Russia) for several decades forbade the printing of books or newspapers in Lithuanian (with maybe an exception if it was done in a Cyrillic-script orthography which no one knew and no one wanted to learn?); and 3) the devisers of the new standard orthography had their own political agenda, because Lithuanian nationalist sentiment of the time was hostile to Polish nationalist sentiment, viewing it as a problematic rival rather than a natural ally in the struggle against Russian nationalism — so maximizing visual differentiation from Polish via orthographic convention made a lot of sense to them. The key difference from the Hokkien-creationist situation, however, might be that the Lithuanian orthography reformers were perfectly well aware of the prior tradition and deviated from it on purpose as opposed to incorrectly thinking there just wasn't enough of a useful model to be followed so they had to start afresh out of necessity.

A-gu said,

September 21, 2016 @ 9:08 pm

Great post!

@Janet Williams:

Seeing 憂鬱 reminded me of how often Taiwan newspaper headlines use the Hokkien 鬱卒 ut-tsut instead!

Wentao said,

September 21, 2016 @ 11:07 pm

@Janet Williams

憂 is simplified to 忧, which is formed with the heart radical and the sound-component 尤 yóu. 鬱/郁 is a merger of two existing characters that have the same pronunciation in Mandarin (but not in Middle Chinese and many other topolects, since the former ends in -t and the latter in -k).

KIRINPUTRA said,

September 22, 2016 @ 11:56 am

@Bathrobe

Thanks! And, no doubt about it.

@JS @A-gu

Thanks!

@J.W. Brewer

That sounds similar: sounds like in both cases there was some kind of a “socio-cultural” class dimension in play.

@flow

Thanks for the thoughtful comment! As for the “Why not at least try part”… Without a big name to help society get past the “Eww, a new idea — I hate new ideas” stage, the best bet for attaining “Hologana nirvana” might be to go back to KAC-style ateji first. For instance, Sino-cognate-less MA syllables tend to be written with Hanji that include 馬; HIANN syllables tend to be written with Hanji that include 兄; and so on. In time these “Manyōgana” could be “codified”, fitted with tone markers, and (optionally) visually set apart from regular Hanji. (Would love to talk about this more elsewhere. How did You mark Mandarin tones using Hangeul?)

@Simon P

It’s not that we “can’t” make up our mind. It’s more that [the USERS of Written Hokkien through 1960] “did” make up their mind, only for an incoming ruling class to brush the memo off the desk and change the operating system, then for a later generation of planners (many of them non-users) to come along and say, “Well, the old folks and dead folks obviously couldn’t make up their minds to save their lives, so here’s what we’ll do…”

Also, Cantonese is an interesting comparison: it's drawn the same kind of Zhōngwén-ization activists as Hokkien. These are the people who say 唔 should be 毋 (“Look, the Taiwanese are doing it!”); 啲 should be 尐; 冇 should be 無, etc. But Written Cantonese is socially strong enough to shrug these suggestions right off. For Taiwanese they’re front and center, but with Cantonese they’re fringe. There but for the grace of God…

Victor Mair said,

September 22, 2016 @ 2:47 pm

From Tsu-Lin Mei:

荔镜记 is written in the 潮州 dialect and does not represent Minnan 闽南。Minnan consists of 泉州 and 漳州, the source of Minnan (or Hokkien) spoken in Taiwan.

Van der Loon, “The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies”, Parts I & II, Asia Major, 1966 describes “Doctrina Christiana” , composed by Spanish Dominican fathers to teach their followers, Minnan speakers in Manila, Christian doctrines such as the Lord’s Prayer. Van der loon included a sample as appendix to his paper. Minnan is written in Chinese characters (俺爹你在天上),underneath is Romanization, evidently for the use of Dominican padres (lan tia lu tu t’i chio), which is “Our father who art in Heaven”.

Doctrina christiana: Primer libro impreso en Filipinas. Manila: Imprenta de la Realy Pontificia Universidad de Santo Tomas de Manila, 1951. I have seen a copy of this book in our library. The original was sometime before 1600 when there was a large scale massacre of Chinese immigrants by the locals. The woodblock carving of the Chinese characters indicates that the printer was Chinese.

Van der Loon mentions a manuscript written in Spanish in the British Museum (Add, 25 317), 2a-224b: “Bocabulario de lengua sangleya por las letraz de el A.B.C.”(The vocabulary of the language of Chinese immigrants transcribed in A. B. C. letters). I have seen a copy in Taiwan, at the Institute of Linguistics. The Hokkien vocabulary is in Romanization; the gloss is in Spanish. I suggested to the Institute that the gloss should be translated into Chinese or English, and the ms. should be made more available but nothing was done.

In the 90’s Alain Peyraube discovered another copy of the “Bocabulario” in Barcelona, and it created a stir. But nothing followed.

KIRINPUTRA said,

September 23, 2016 @ 6:02 am

@Victor Mair

That DOCTRINA CHRISTIANA is intriguing. How the Hokkien was written would be interesting no matter how it was written.

What's your take on NĀIKÈNGKÌ being in Teochew, not Hokkien? Could it be that Mei based his views on a different edition?

As for the massacre, I think he's referring to the Massacre of 1603. It was really the Spanish that made it happen, not the natives.