Archive for Writing systems

Twitter length restrictions in English, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean

Josh Horwitz has a provocative article in Quartz (9/27/17): "SAY MORE WITH LESS: In Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, 140 characters for Twitter is plenty, thank you"

The thinking here is muddled and the analysis is misplaced. There's a huge difference between "characters" in English and in Chinese. We also have to keep in mind the difference between "word" and "character", both in English and in Chinese. A more appropriate measure for comparing the two types of script would be their relative "density", the amount of memory / code space required to store and transmit comparable information in the two scripts.

Read the rest of this entry »

Cultural invasion

Article in South China Morning Post (9/19/17) by Jasmine Siu:

"Activist fined HK$3,000 for binning Hong Kong public library books in ‘fight against cultural invasion’ from mainland China: Alvin Cheng Kam-mun, 29, convicted of theft over dumping of books printed in simplified Chinese characters"

A radical Hong Kong activist was on Tuesday fined HK$3,000 for dumping library books in a bin in what he said was an attempt to protect children from the “cultural invasion” of simplified Chinese characters.

Read the rest of this entry »

Neo-Nazi kanji

Tattoo on the shoulder of a marcher in Charlottesville on Saturday, August 12:

Source: "A lot of white supremacists seem to have a weird Asian fetish," Vice News, Dexter Thomas (9/12/17)

Read the rest of this entry »

The sociolinguistics of the Chinese script

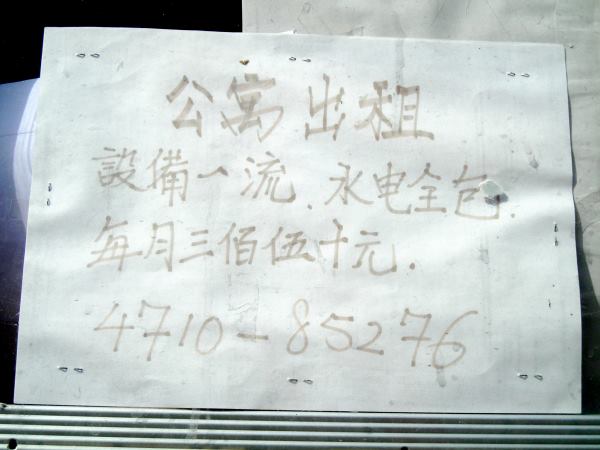

Jonathan Benda posted this on Facebook recently:

Reading [Jan Blommaert's] _Language and Superdiversity_ in preparation for my Writing in Global Contexts course in the fall. Does anyone else think the following conclusions about this sign are somewhat wrongheaded?

Read the rest of this entry »

Learning languages is so much easier now

If you use the right tools, that is, as explained in this Twitter thread from Taylor ("Language") Jones.

A brief thread on how kids have it (in this case, language learning) easier these days.

When I first studied Chinese in college… 1/

— Language Jones (@languagejones) August 17, 2017

Rule number 1: Use all the electronic tools at your disposal.

Rule number 2: Do not use paper dictionaries.

Jones' Tweetstorm started when he was trying to figure out the meaning of shāngchǎng 商场 in Chinese. He remembered from his early learning that it was something like "mall; store; market; bazaar". That led him to gòuwù zhòngxīn 购物中心 ("shopping center"). With his electronic resources, he could hear these terms pronounced, could find them used in example sentences, and could locate actual places on the map designated with these terms.

Read the rest of this entry »

GAN4 ("Do it!")

From a long blog post on contemporary Chinese religious art and architecture:

Read the rest of this entry »

GA

One of my favorite Chinese words is GANGA (pronounce as in "Lady Gaga", but put a nasal at the end of the first syllable). It is so special and has had such a deep impact upon me since I began learning Chinese half a century ago that, in this post, I shall refer to it simply as "GANGA", in capital letters only, except when discussing its more precise pronunciation, derivation, meaning, and written representation in Chinese characters. Referring to this unusual word as "GANGA" is meant to emphasize the iconic quality it has for me personally, in the sense that its nature reveals many verities about Sinitic languages and Chinese writing.

Read the rest of this entry »

Chinese Synesthesia

Xiaoyan (Coco) Li, a native Chinese speaker with synesthesia (self identified, never formally tested), happened to come across this Language Log post:

"Synesthesia and Chinese characters" (3/9/17)

She wrote to me saying that she experiences some of what Leo Fransella (quoted in the earlier post) referred to as "'non-trivial' Chinese synaesthesia". For him "trivial" Chinese synesthesia is associated with or stimulated by the letters of the Pinyin used to spell Chinese words, not from the characters used to write them.

Read the rest of this entry »

Cantonese: still the main spoken language of Hong Kong

Twenty years ago today, on July 1, 1997, control of Hong Kong, formerly crown colony of the British Empire, was handed over to the People's Republic of China. The last few days has seen much celebration of this anniversary on the part of the CCP, with visits by Xi Jinping and China's first aircraft carrier, as well as a show of force by the People's Liberation Army, but a great deal of anguish on the part of the people of Hong Kong:

"Once a Model City, Hong Kong Is in Trouble" (NYT [6/29/17])

"Xi Delivers Tough Speech on Hong Kong, as Protests Mark Handover Anniversary" (NYT [7/1/17])

"China's Xi talks tough on Hong Kong as tens of thousands call for democracy" (Reuters [7/1/17])

"China 'humiliating' the UK by scrapping Hong Kong handover deal, say activists: Pro-democracy leaders say Britain has ‘legal, moral and political responsibility’ to stand up to Beijing" (Guardian [7/1//17])

"Tough shore leave rules for Chinese navy personnel during Liaoning’s Hong Kong visit: The crew from China’s first aircraft carrier will be prohibited from enjoying Western-style leisure activities during city handover anniversary visit" (SCMP [6/28/17])

All of this political maneuvering has an impact on attitudes toward language usage in Hong Kong.

Read the rest of this entry »

Simplified characters for Hong Kong? No thanks!

On July 1, the government is sponsoring a spectacular fireworks display that will light up the sky over Victoria Harbor to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong from British colonial control to the People's Republic of China. Trouble is, the show will begin with the words "China" and "Hong Kong", but the form in which they will be written has made local residents unhappy:

"Hong Kong fireworks display for 20th handover anniversary sparks controversy over use of simplified Chinese characters: City’s most expensive fireworks event since 1997 to run 23 minutes over Victoria Harbour at cost of HK$12 million" (Jane Li, SCMP, 6/12/17)

Read the rest of this entry »