Archive for Philology

March 27, 2024 @ 5:06 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Epigraphy, Philology

From Tlacuilolli*, the blog about Mesoamerican writing systems, by Alonso Zamora, on March 21, 2024:

*At the top left of the home page of this blog, there is a tiny seated figure (click to embiggen) with a sharp instrument held vertically in his right hand carving a glyph on a square block held in his left hand. Emitting from his mouth is a blue, cloud-like puff. Does that signify recognition the basis of what he is writing is speech?

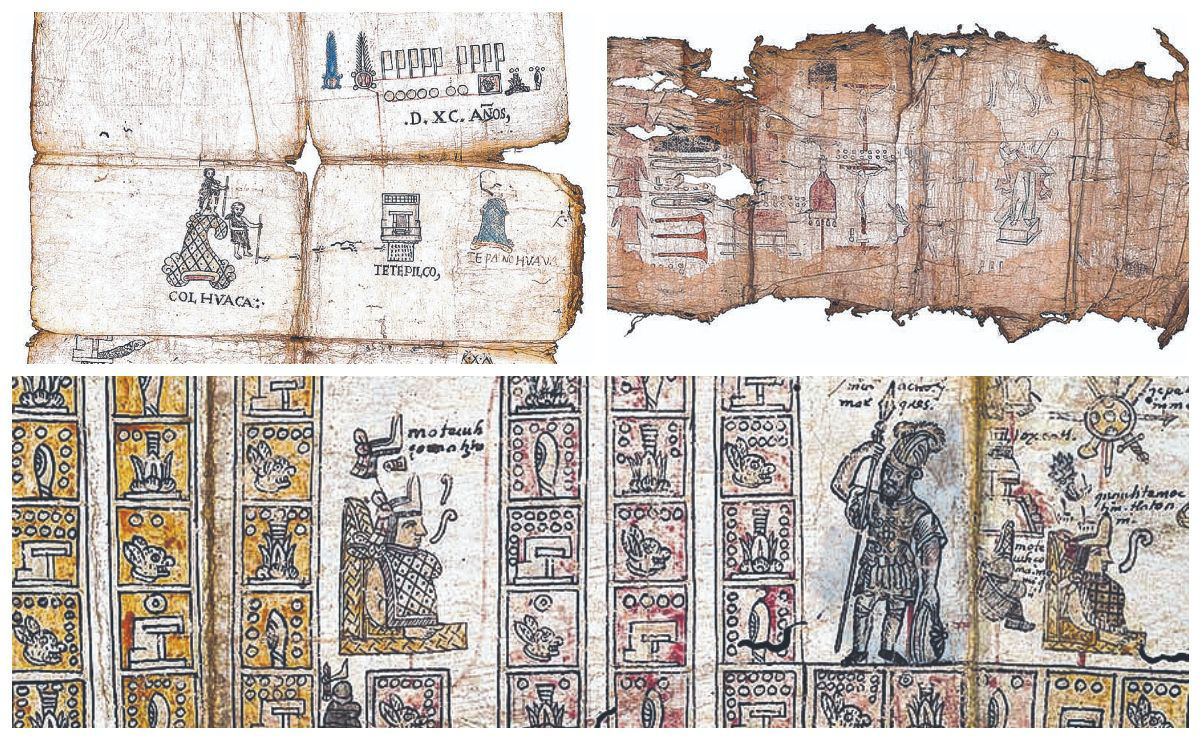

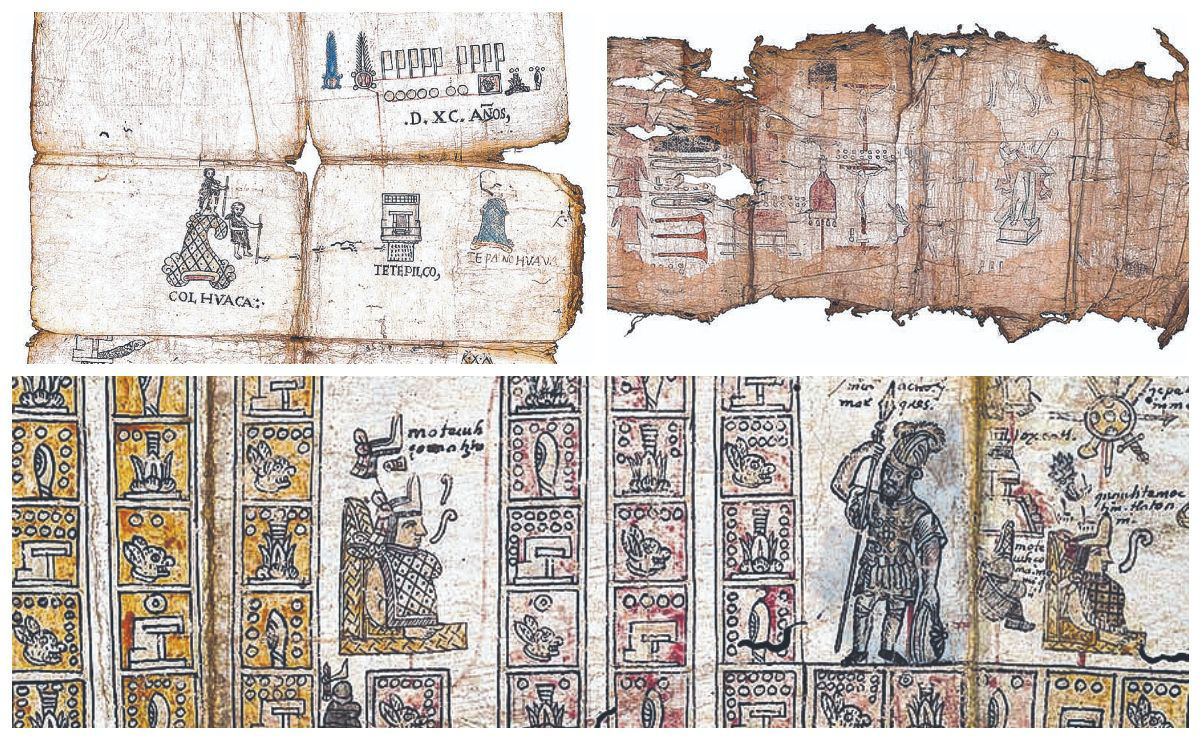

"New Aztec Codices Discovered: The Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco"

They are beautiful:

Figure 1. Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco: a) Map of the Founding of San Andrés Tetepilco;

b) Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco; c) Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 6, 2024 @ 6:49 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Data bases, Language and food, Philology

Sino-Platonic Papers is pleased to announce the publication of its three-hundred-and-thirty-eighth issue:

“Mapping the Language of Spices: A Corpus-Based, Philological Study on the Words of the Spice Domain,” by Gábor Parti.

ABSTRACT

Most of the existing literature on spices is to be found in the areas of gastronomy, botany, and history. This study instead investigates spices on a linguistic level. It aims to be a comprehensive linguistic account of the items of the spice trade. Because of their attractive aroma and medicinal value, at certain points in history these pieces of dried plant matter have been highly desired, and from early on, they were ideal products for trade. Cultural contact and exchange and the introduction of new cultural items beget situations of language contact and linguistic acculturation. In the case of spices, not only do we have a set of items that traveled around the world, but also a set of names. This language domain is very rich in loanwords and Wanderwörter. In addition, it supplies us with myriad cases in which spice names are innovations. Still more interesting is that examples in English, Arabic, and Chinese—languages that represent major powers in the spice trade at different times—are here compared.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

November 29, 2023 @ 10:38 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Diction, Grammar, Language teaching and learning, Pedagogy, Philology, Phonetics and phonology, Pronunciation

[This is the first of two consecutive posts on things Indian. After reading them, if someone is prompted to send me material for a third, I'll be happy to make it a trifecta.]

Our entry point to the linguistically compelling topic of today's post is this Nikkei Asia (11/29/23) article by Barkha Shah in its "Tea Leaves" section:

Why it's worth learning ancient Sanskrit in the modern world:

India’s classical language is making a comeback via Telegram and YouTube

The author begins with a brief introduction to the language:

The language had its heyday in ancient India. The Vedas, a collection of poems and hymns, were written in Sanskrit between 1500 and 1200 B.C., along with other literary texts now known as the Upanishads, Granths and Vedangas. But while Sanskrit became the foundation for many (though not all) modern Indian languages, including Hindi, it faded away as a living tongue.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 8, 2023 @ 1:05 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and religion, Language and the movies, Philology

No, I'm not talking about the eye parasite called Loa loa (a filarial nematode), which is also called eyeworm. I'm talking about an image that gets stuck in your brain the same way an earworm (also called brainworm, sticky music, or stuck song syndrome) gets stuck in your head. We've talked about earworms a lot on Language Log (see "Selected readings" below for a few examples), but I don't think we've ever mentioned eyeworms before.

No, come to think of it, I did use the word "eyeworm" once before (here), but that was in reference to the ubiquitous subtitles of Chinese films, even those intended for Chinese audiences, which — upon first glance — may strike one as unnecessary excrescences crawling around in the viewer's field of vision, except for the reasons I listed in the cited post, which lead Chinese audiences to prefer or even need them to understand the films they are watching.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 23, 2023 @ 8:46 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Grammar, Philology

Beautiful WSJ OpED (6/22/23) by Gerard Gayou, a seminarian of the archdiocese of Washington, who is studying theology at the Pontifical North American College in Rome:

The Guiding Light of Latin Grammar

The language reminds us of what our words mean and of whom we’re called to be.

—–

Nothing bored me more during the summer of 2008 than the prospect of studying Latin grammar. I needed a foreign language as part of my high-school curriculum, and I was loath to choose a dead one. I opted instead for Mandarin Chinese, an adolescent whim that shaped my young adult life. I continued to learn Mandarin in college before working in mainland China after graduation.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 8, 2023 @ 7:24 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Philology, Phonetics and phonology, Reconstructions, Words words words

Sino-Platonic Papers is pleased to announce the publication of its three-hundred-and-thirty-first issue:

Bettina Zeisler, “Combinatory Sound Alternations in Proto-, Pre-, and Real Tibetan: The Case of the Word Family *Mra(o) ‘Speak,’ ‘Speaker,’ ‘Human,’ ‘Lord’” (free pdf), Sino-Platonic Papers, 331 (March, 2023), 1-165.

Among many other terms, discusses the Eurasian word for "horse" often mentioned on Language Log (see "Selected readings" below for examples). Gets into IIr and (P)IE.

ABSTRACT

At least four sound alternations apply in Tibetan and its predecessor(s): regressive metathesis, alternation between nasals and oral stops, jotization, and vowel alternations. All except the first are attested widely among the Tibeto-Burman languages, without there being sound laws in the strict sense. This is a threat for any reconstruction of the proto-language. The first sound alternation also shows that reconstructions based on the complex Tibetan syllable structure are misleading, as this complexity is of only a secondary nature. In combination, the four sound alternations may yield large word families. A particular case is the word family centering on the words for speaking and human beings. It will be argued that these words ultimately go back to a loan from Eastern Iranian.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 1, 2023 @ 10:19 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Philology

Meant to send this more than a month ago.

Interesting new journal in Iranian Studies

"Berkeley Working Papers in Middle Iranian Philology is a new open access e-journal hosted by UC Berkeley’s Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures and edited by Adam Benkato and Arash Zeini. It publishes short and longer articles or research reports on the philology and epigraphy of the Middle Iranian languages (Middle Persian, Parthian, Bactrian, Sogdian, Chorasmian, Khotanese). Submitted papers will be reviewed by the editors and published on an ongoing basis. The journal promotes a simple and quick publishing process with collective annual volumes published at the end of each year. The editors encourage scholars working on Middle Persian documents in particular to submit their work."

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 12, 2023 @ 8:42 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Artificial intelligence, Decipherment, Philology

Once again, DH to the rescue:

AI Deciphers Ancient Babylonian Texts And Finds Beautiful Lost Hymn

Eat your heart out, ChatGPT.

Tom Hale, IFLScience (2/7/23)

It used to be that paleographers and philologists labored mightily trying to piece together bits and pieces of old manuscripts, using only their own mental and visual powers. Now they can call on AI allies to provide decisive assistance.

Researchers have crafted an artificial intelligence (AI) system capable of deciphering fragments of ancient Babylonian texts. Dubbed the “Fragmentarium,” the algorithm holds the potential to piece together some of the oldest stories ever written by humans, including the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

September 7, 2022 @ 8:33 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Information technology, Language and computers, Language and literature, Philology

Just out today, this is one of the longest book reviews I have ever written:

Jack W. Chen, Anatoly Detwyler, Xiao Liu, Christopher M. B. Nugent, and Bruce Rusk, eds., Literary Information in China: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

Reviewed by Victor H. Mair

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright September, 2022)

I am calling it to your attention because the book under review, which I will refer to here as LIIC, signals a sea change in:

1. Sinology

2. Information technology

3. Academic attitudes toward the study of language and literature

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

May 9, 2022 @ 2:00 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Books, Etymology, Lexicon and lexicography, Philology

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 15, 2022 @ 6:55 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Classification, Historical linguistics, Language contact, Numbers, Philology, Phonetics and phonology, Reconstructions, Variation

[This is a guest post by Penglin Wang]

The great difficulties we have with trying to study Xiongnu language persist from trying to glean Xiongnu words, especially the glossed ones, in early Chinese sources for comparison in order to know what linguistic affiliation it seems to have in the central Eurasian region. Since these difficulties cannot be overcome at all owing to its extinct status a millennium plus ago, an alternative approach could be to recognize that there are different components of language regardless of living or extinct and attempt to observe how different components can differ from one another yet still be entities that most researchers would want to treat as linguistic data or facts rather than imaginations for a comparative purpose. It could then be possible to open up a window to contribute to a solution of some classic problems in Altaic comparative studies. One such attempt is to examine the available Xiongnu words from the perspectives of articulatory phonetics and phonotactics. Concern for these is characteristic of Xiongnu studies. Pulleyblank (1962:242) has insightfully observed “only *b- initially, never *p-” in the Xiongnu transcriptions.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 5, 2022 @ 6:56 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Etymology, Language and archeology, Language and business, Language and culture, Morphology, Philology

During the early part of my career, one of the most stunning academic papers I read was this:

During the early part of my career, one of the most stunning academic papers I read was this:

Roy Andrew Miller, "Pleiades Perceived: MUL.MUL to Subaru", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 108.1 (January-March, 1988), 1-25.

"Pleiades Perceived" was the presidential address delivered March 24, 1987 at the American Oriental Society's 197th Annual Meeting in Los Angeles. "Roy Andrew Miller (September 5, 1924 – August 22, 2014) was an American linguist best known as the author of several books on Japanese language and linguistics, and for his advocacy of Korean and Japanese as members of the proposed Altaic language family." (source)

Miller received his Ph.D. in Chinese and Japanese from Columbia University. He taught successively at the International Christian University in Tokyo, Yale University, and the University of Washington. He was (in)famous for his harsh reviews, to be compared only with those of Leon Hurvitz (August 4, 1923 – September 28, 1992), who also received his Ph.D. from Columbia and, after teaching at the University of Washington, ended his career at the University of British Columbia. Miller and Hurvitz both were immensely learned scholars who knew Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, and other challenging languages. I didn't meet Miller in person, but did study for one year with Hurvitz, who was extraordinarily eccentric.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 8, 2022 @ 8:03 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Idioms, Language and geography, Language and literature, Metaphors, Philology, Translation, Writing systems

Dieter Maue, a specialist on Old Uyghur, Tocharian, Sanskrit, and Brahmi script, wrote to ask:

The simile 'like the moon of the third day' (tertium comparationis: delicate, graceful; curved (eyebrows)) is currently occupying my mind. Attested in Tocharian A and in Uigur, it sounds, but it doesn't seem to be, Indian.

Tentatively I have translated Uig. üč yaŋıdakı ay täŋri ‘third day’s moon god’ into Chinese word for word; but sān rì yuè 三日月("moon of the third day") is not found in the dictionaries. In the Chinese Tripitaka, there is just one suitable instance. Elsewhere, the moon of the third day seems to be called éméi yuè 蛾眉月 ("moth eyebrow moon" — only poetically?). According to Giles (ChinEnglDict s.no. 7714 ): “ éméi 蛾眉 moth eyebrows, – alluding to the delicate curved eye-markings of the silkworm moth … moth-eyebrows is used figuratively for a lovely girl. Also wrongly explained as referring to the small curved antennæ of the silkworm moth. Éméi yuè 蛾眉月‚ the crescent moon’. “ The antennae of Bombyx mori are clearly visible, while I cannot find anything which corresponds to the “eye-markings”. Do you have an idea how to solve the problem?

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

During the early part of my career, one of the most stunning academic papers I read was this:

During the early part of my career, one of the most stunning academic papers I read was this: