The importance of rhythm for memorization

My wonderful 2nd grade teacher taught me how to spell Mississippi with a special sing-song rhythm, and I've never forgotten it thereafter. Her jingle makes spelling "Mississippi" — whose shape is as contorted as its riverine course and scared me the first few times I tried to spell it myself, before she taught me the secret / knack — as easy as falling off a log.

Unfortunately, I never learned how to spell "Cincinnati" that way, so I always have to proceed carefully and cautiously when I spell the name of that awesome city in the southwest corner of my home state.

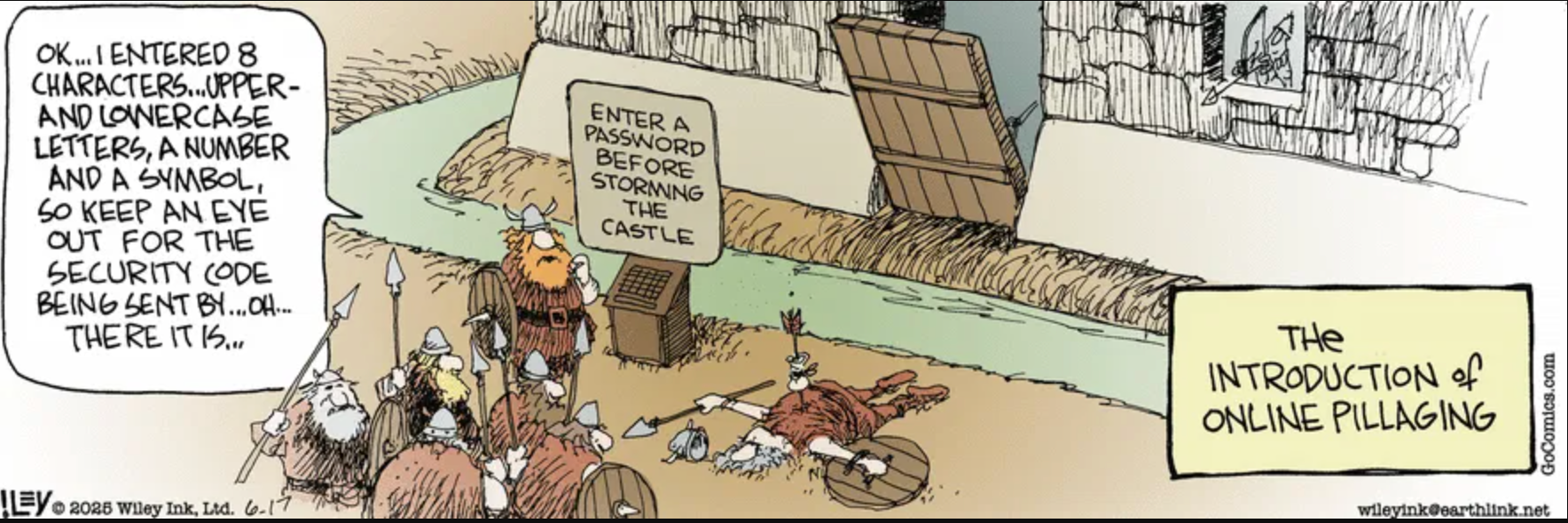

I use a similar technique for remembering my social security number, phone number, lock combinations, and so forth. But I have not been able to apply it to recalling computer passwords, which are a terrible trial for me (ask the department staff and IT guys at Penn how awful I am with passwords and the like). Maybe the reason rhythmic memorization don't work for passwords is that we have many of them for different purposes, plus they require weird combinations of upper and lower case letters, an arbitrary number of numbers, and a set amount of nonalphanumeric symbols.

Read the rest of this entry »