Tragic Effle

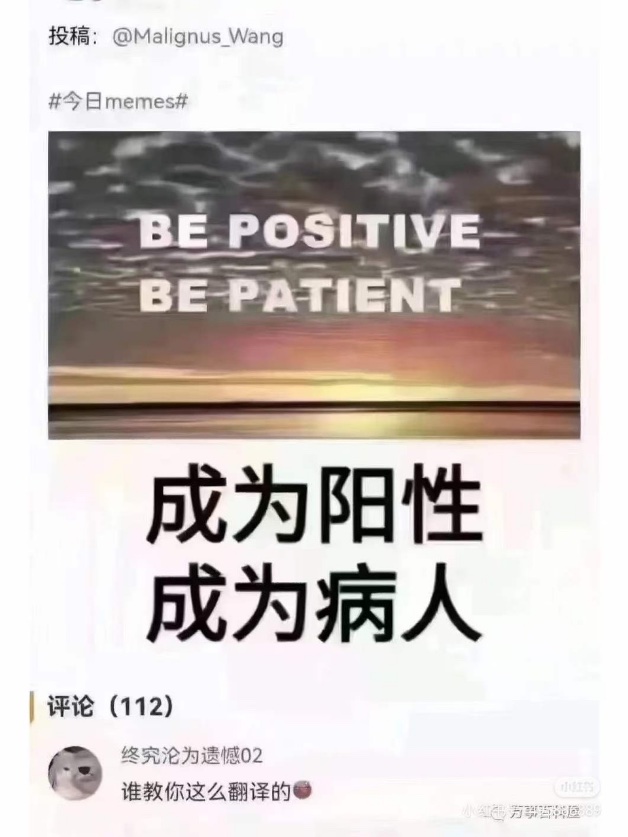

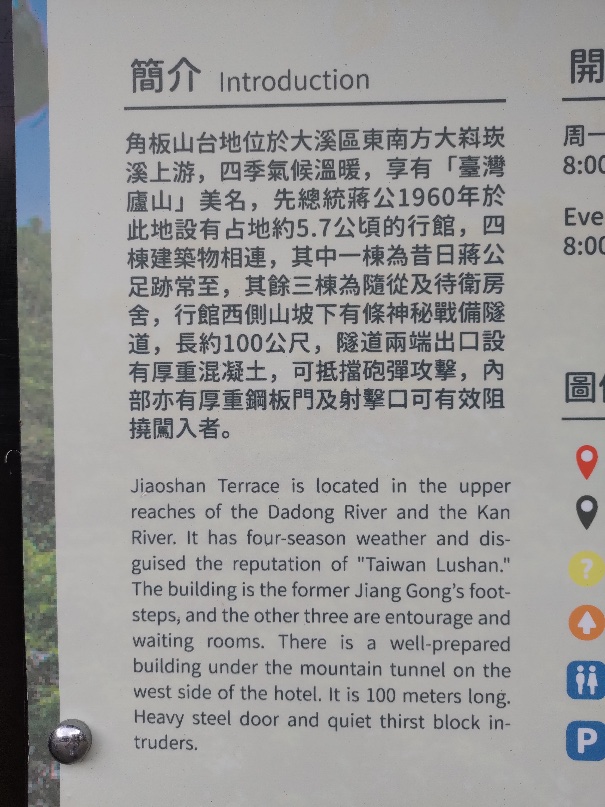

In "Vintage Effle" (12/18/2003) I linked to "the Effle Page, which introduces a useful word for the pseudo-language of many phrase books", and informs us that

The playwright Eugene Ionesco wrote a complete play in Effle, The Bald Prima Donna, the product of his experience of learning English from a textbook in 1950. He actually wrote the play in French, but it shows its origins clearly when translated back into English.

Futility Closet for New Year's Eve 2024 offer the English side of a phrase list from Collins' Pocket Interpreters: France (1937 edition), observing that

James Thurber, who came upon the book in a London bookshop, described it as a “melancholy narrative poem” and “a dramatic tragedy of an overwhelming and original kind.” “I have come across a number of these helps-for-travelers,” he wrote, “but none has the heavy impact, the dark, cumulative power of Collins’.

Read the rest of this entry »