Negotiating with hallucinations: Two controlled trials

« previous post | next post »

Jenny Kleeman, "‘You tried to tell yourself I wasn’t real’: what happens when people with acute psychosis meet the voices in their heads?" The Guardian, 10/29/2024: "In avatar therapy, a clinician gives voice to their patients’ inner demons. For some of the participants in a new trial, the results have been astounding."

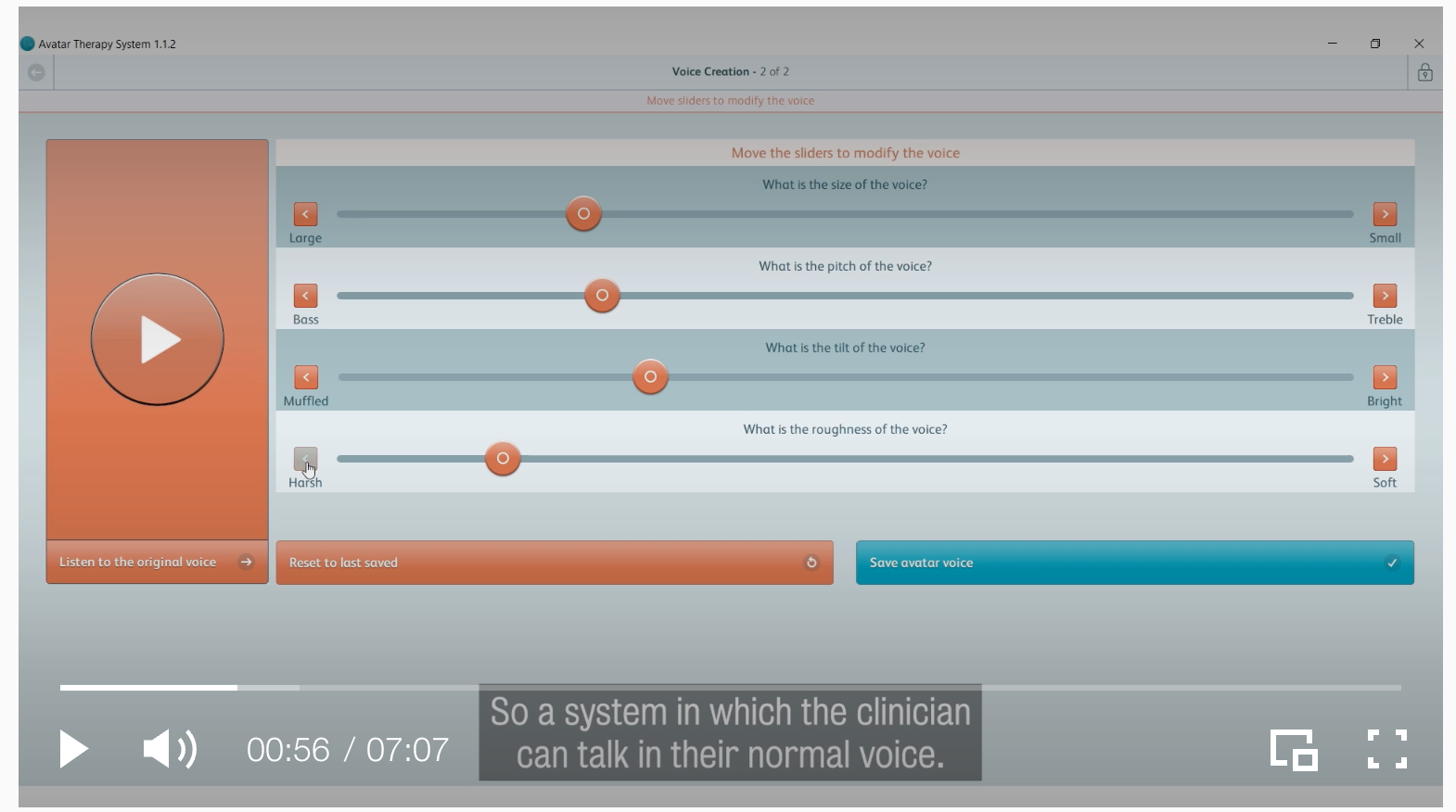

I learned about early trials of this idea about 15 years ago from Mark Huckvale, who developed the voice-morphing technology that allows a therapist to sound like (one of) the hallucinated speakers, through a dashboard that looks like this:

And Mark is one of the authors of the 2018 paper that the Guardian article leads with: Tom Craig et al., "AVATAR therapy for auditory verbal hallucinations in people with psychosis: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial". The Lancet January 2018.

I discussed this approach in an earlier post, "Negotiating with hallucinations", 8/9/2012. The system that Mark showed me is evocatively described in the Guardian article:

Prof Julian Leff was seven years into his retirement when the idea of avatar therapy came to him. After a celebrated career as a social psychiatrist and schizophrenia specialist at University College London, Leff was sitting at home in Hampstead, pondering the results of a survey that reported the most distressing aspect of hearing voices was the feeling of helplessness. On the rare occasions when his patients had had meaningful exchanges with their voices, he knew they had felt more in control. “I thought, how can I enable the patient to have a dialogue with an invisible voice?” Leff said in an interview for a documentary made in 2018, three years before his death. “If I can somehow manage to create for the patient the image and voice of the person who they hear abusing them, maybe they could learn to overcome this awful persecution.”

Leff was awarded a small grant for a pilot study in 2008. He recruited Mark Huckvale, professor of speech, hearing and phonetic sciences at UCL, to be in charge of the tech. They tinkered with existing police identikit software, animating digitally created faces in three dimensions so they could nod, smile and maintain eye contact. They combined this with an off-the-shelf programme called Lip Synch, so that the mouth would move appropriately, and voice-changing software, so the avatar could be made to sound male or female, rougher or smoother, higher or lower, older or younger.

The avatar was a floating, moving head on a computer screen, voiced by Leff, who would be in a separate room to the patient, watching via webcam. He could speak to the patient in his own voice, guiding them through the dialogue, and then switch with the click of a mouse to the role of the avatar on the patient’s screen, its lips synched to his speech. The setup allowed him to act as a therapist to the patient and a puppeteer to the avatar. At first, the avatar would say typical lines the patient had shared with Leff: often degrading, abusive phrases. But over the course of six sessions, the dialogue would change, with the avatar yielding to the patient, transforming from omnipotent to submissive. At all times, Leff and the patient were to treat the avatar as if it were an entirely real third party.

The "new trial" of this approach is documented in Philippa Garety et al., "Digital AVATAR therapy for distressing voices in psychosis: the phase 2/3 AVATAR2 trial", Nature Medicine 10/28/2024:

Distressing voices are a core symptom of psychosis, for which existing treatments are currently suboptimal; as such, new effective treatments for distressing voices are needed. AVATAR therapy involves voice-hearers engaging in a series of facilitated dialogues with a digital embodiment of the distressing voice. This randomized phase 2/3 trial assesses the efficacy of two forms of AVATAR therapy, AVATAR-Brief (AV-BRF) and AVATAR-Extended (AV-EXT), both combined with treatment as usual (TAU) compared to TAU alone, and conducted an intention-to-treat analysis. We recruited 345 participants with psychosis; data were available for 300 participants (86.9%) at 16 weeks and 298 (86.4%) at 28 weeks. The primary outcome was voice-related distress at both time points, while voice severity and voice frequency were key secondary outcomes. Voice-related distress improved, compared with TAU, in both forms at 16 weeks but not at 28 weeks. […] Voice severity improved in both forms, compared with TAU, at 16 weeks but not at 28 weeks whereas frequency was reduced in AV-EXT but not in AV-BRF at both time points. There were no related serious adverse events. These findings provide partial support for our primary hypotheses. AV-EXT met our threshold for a clinically significant change, suggesting that future work should be primarily guided by this protocol.

A public-facing page for the project is available at Avatar 2, including this visual "Trial Summary".

The Guardian article has some impressive and evocative descriptions of the process — you should read the whole thing, but here's a taste:

Joe was nervous about designing his avatar. No one had ever asked him to describe what his voices looked or sounded like before. He had spent so much energy telling himself they couldn’t be real and now he had to manifest them in the real world. There were other challenges: like most people with psychosis, Joe heard several voices, and he experienced them more as a felt presence, rather than a single entity with a definite physical appearance and a familiar face.

Tom Ward, who was assigned to be Joe’s therapist, told me the average number of voices heard by people with psychosis is four. “We are looking for the dominant voice that’s causing the most distress.” Joe chose the voice who told him there was no point in living because he was already dead.

He and Ward began creating the avatar’s face. There was a blizzard of choices in drop-down menus on Ward’s laptop screen: is it a human or non-human entity? If it’s human, what is its gender, age, height (tall, medium, short), ethnicity (European, east Asian, south Asian, African)? If it’s non-human, does it take the form of a devil, angel, alien, vampire, robot, witch, goblin, elf, beast? Once a basic form is chosen, there are sliders to change the physiognomy: making the nose broader, thinner, shorter or longer; adjusting the eyes, brow and chin; modifying the hairstyle.

Joe found it hard to describe what the voice looked like: it was often hooded, masked, out of focus, only partially visible. It was demonic, but it didn’t look like a devil. Together, they created the head of a bald man with olive skin, like Joe’s. He chose between five versions of voices, and used sliders to change the pitch, tilt and roughness. The final voice was deeper than any human’s. That’s what made it demonic, for Joe.

It wasn’t exactly right, but once Joe was alone with the screen there was something about the avatar that resonated. Ward reminded Joe he was there to support him. Before they went into their separate rooms, they had practised what the avatar was going to say, and how Joe might respond to it. Still, he felt terrified.

“You’re already dead,” the avatar told him, in a voice that was almost monotone. “You’ve been in hell all this time and this is your existence from now on.”

“If this is death, it’s exactly the same as what my idea of life was,” Joe replied, a little meekly. He was surprised by how realistic the experience was, how true to life this felt.

“You’re lying to yourself,” the voice retorted.

In his own, encouraging voice, Ward reassured Joe, reminding him to hold eye contact, to communicate in strong messages that he was in charge.

“You’re harder to get hold of today,” the avatar said towards the end of the first session. “You can’t keep it up.”

“I can keep this up for ever, and I will,” Joe replied. “It’s my life. I have the autonomy here. I’m in control.”

Joe had 12 weekly sessions. The darkest exchange came in the fourth.

“You should end it,” the avatar said, casually. “What have you done that’s of any use to anyone?”

Joe couldn’t answer this.

In his own voice, Ward interjected to remind Joe about his relationships, his family, the life he had been able to make for himself. “What the avatar is saying is actually not true,” Ward said. “Can you come back with positives?”

Ward switched back to voicing the avatar. “You agree with me deep down,” it sneered. “You haven’t done anything of use.”

“No,” Joe said, firmly. “I have a lot of good friendships. I think on balance I have had a good life. It’s been positive. I’ve got more to do.”

“You’re handling yourself better than I thought,” the avatar replied. “I’d thought you’d be falling apart by now.”

The article tells us more about Joe's dialogues with his voice — "By Joe’s seventh session, he was having insightful, poignant conversations with the avatar. […] The dialogue had become a strange kind of couples therapy […] Joe began to feel compassion – even pity – for his tormentor. "

Philip Taylor said,

October 30, 2024 @ 1:00 pm

Well worth reading, as you say Mark. As an (e-)Guardian reader, I was aware of the article before your Language Log post, but it was only because of your post that I actually read the article. Thank you.

Seth said,

October 31, 2024 @ 5:37 pm

This reminds me of using image manipulations so people who had limb amputations can scratch a "phantom limb" which itches.

But there must be something very deep going on if people accept the avatar as the entity itself. Why doesn't the entity say "That's ridiculous. I'm here in your head. You're just talking to someone or something else imitating my voice. If another person imitated your voice, or put on a disguise to look like you, that wouldn't make them you, would it? What a silly idea.".

Maybe I've read too many genre stories, as I keep thinking any spirit malicious enough to torment someone, would find this hilariously absurd.

John Swindle said,

November 2, 2024 @ 12:40 pm

An eccentric American clinical psychologist named Wilson Van Dusen was already writing about interviewing schizophrenic patients' hallucinated voices as part of therapy in the 1970s, without the need for a high-tech avatar.