Turco-Sogdian horses and languages

« previous post | next post »

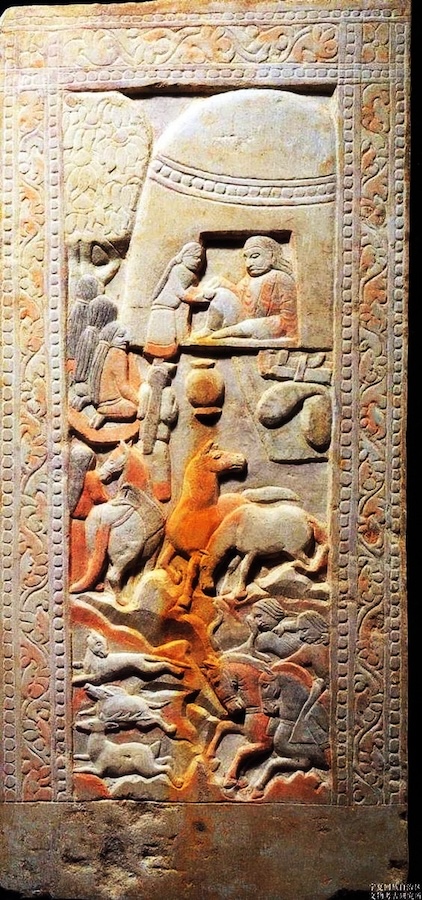

Reading through Étienne de La Vaissière's massive magnum opus, Asie Centrale 300-850: Des routes et des royaumes (2024), I came to a screeching halt when my gaze alighted on this photograph (III.6, p. 71):

Limestone relief of Saluzi ("Autumn Dew"), one of the Six Steeds of Zhao Mausoleum, along with an unknown human general. The general switched horses with the emperor and cared for Saluzi; he is seen here pulling an arrow out of Saluzi's chest. On display at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (source)

Beneath it was the caption: "Cheval sogdien de Taizong". After reading it, all the more I was unable to advance. You see, I know that horse very well, for he is depicted on one of the stone reliefs of the Tang emperor Taizong's (598-649) six noble steeds (war horses), two of which are preserved in The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

For a detailed, book-length account of the origin of the six stone horses at the mausoleum of Emperor Taizong on Zhao Ling in Shaanxi Province, northwest China and the history of how two of the reliefs came to Penn, see Xiuqin Zhou's Creation and Separation: A Chinese Emperor's Six Stone Horses (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2024), xlviii, 350 pages.

What arrested me so abruptly was that I never thought of Saluzi and his equine companions as being Sogdian horses. I wasn't sure what his pedigree was, but I thought of him more — in terms of medieval horsebreeding — as Turkic, but before that as Bactrian.

Here are the names of Taizong's six noble steeds:

- Quanmaogua (拳毛騧), Taizong's steed during the campaign against Liu Heita.

- Shifachi (什伐赤), ridden during the Battle of Hulao against Dou Jiande. Its name derives from the Turkic term Shad.

- Baitiwu (白蹄乌), ridden during the campaign against Xue Rengao.

- Telebiao (特勒骠), ridden during the campaign against Song Jingang. Its name is originally 特勤 Teqin, derived from the Turkic term Tegin.

- Qingzhui (青骓), ridden during the campaign against Dou Jiande.

- Saluzi (飒露紫), ridden during the campaign against Wang Shichong. Its name derives from the Turkic 'Isbara', itself a derivation from the Sanskrit 'Isvara' meaning prince.

(source)

It is evident that at least half of the names are of Turkic derivation.

There's no doubt that, from classical (e.g., Han Dynasty, roughly 2nd) times, the Chinese were desperately in need of procuring excellent horses to fend off the very Central Asian nomads who were so good at producing them, and even went to large-scale war to force the Central Asian peoples to give up some of their best horses. See, for instance, Jonathan Tao, "Heavenly Horses of Bactria:,The Creation of the Silk Road" in Emory Journal of Asian Studies (2019), 1-24 — especially "flying" horses of this sort:

The Gansu Flying Horse, East Han, Bronze, Gansu Provincial Museum (source)

Ferghana horses (Chinese: 大宛馬 / 宛馬; pinyin: dàyuānmǎ / yuānmǎ; Wade–Giles: ta-yüan-ma / yüan-ma) were one of China's earliest major imports, originating in an area in Central Asia. These horses, as depicted in Tang dynasty tomb figures in earthenware, may "resemble the animals on the golden medal of Eucratides, King of Bactria (Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris)."

The Ferghana horse is also known as the "heavenly horse" in China or the Nisean horse in the West. (source)

The most outstanding horses of classical times, the ones that Han Chinese armies went to war over, were associated with the peoples of Bactria and Ferghana, both of whom spoke Old Iranian languages, whereas Sogdians, like their Central Asian confreres the Khotanese, spoke Middle Iranian languages. Moreover, the Sogdians were renowned for their mercantile expertise. They were not known for their marshal prowess. For military purposes, the Sogdians formed a symbiotic relationship with the medieval Turkic peoples.

This cooperative arrangement between Sogdians and Turks is visually evident in the iconography of the famous medieval Sogdian mortuary couches, for which see:

Judith A. Lerner, "Aspects of Assimilation: the Funerary Practices and Furnishings of Central Asians in China", Sino-Platonic Papers, 168 (December, 2005), 51, v, 9 plates.

Patrick Wertmann, Sogdians in China. Archaeological and Art Historical Analyses of Tombs and Texts from the 3rd to the 10th Century AD, Darmstadt: Philipp von Zabern, 2015.

Both of these works offer excellent analyses and illuminating illustrations.

A funerary depiction of long haired Türks in the Kazakh steppe. Miho funerary couch, circa 570. The sumptuous Miho funerary couch is of Sogdian provenience.

Turkic horseman (Tomb of An Jia /Qie, 579 AD; once again a Sogdian nobleman in close association with a Turkic horseman.).

It is clear from textual, artistic, literary, and other types of evidence that the medieval Chinese were greatly desirous of obtaining large numbers of top quality horses and were willing to spend lavishly to obtain them. Even though the Sogdians were skillful traders and probably also excelled at selling horses to the Chinese, I suspect that they were not adept at breeding and rearing horses, but would have had to rely on Turkic and other (e.g., Tibetan) and other Central Asians who were accomplished at doing so.

Searching for a better studied parallel to trade in horses between nomadic Central Asians and settled East Asian populations than we have for the Tang period (618-907), I asked Paul Smith, who undertook decades of detailed research on the tea-and-horse trade during the Song period (960-1279) how it worked then. He told me the following:

I believe the Song situation mirrors that of the Tang and the Sogdians in this way: the horses in the tea-horse trade were primarily from the Qinghai grasslands (as Richard von Glahn, some students, and I saw in 2006). I imagine it this way: The region was controlled by the fractious offshoots of Juesiluo's tribal confederation based eventually in Qingtang/Xining. Merchants, most likely Tibetan, gathered the horses and convoyed them through the various chiefdoms to the Song government markets, where they traded them for tea and other commodities that they deployed back in the other direction. I'm sure all the local potentates were enriched along the way. But merchants were definitely in the middle of it, and it is they with whom the government officials dealt.

The tea-and-horse trade during the Song period was larger scaled and more heavily bureaucratized than the more ad hoc arrangements of the preceding Tang period. Still, it was a cooperative enterprise, with merchants and military men both playing essential roles.

So much for Sogdo-Turkic relationships as they pertain to horse trading with the Han peoples in medieval East Asia.

How did they (the Sogdians and the Turks) interact when it comes to language?

As I was reacting to the notion of a "Sogdian horse" and began to develop a Language Log post on the idea of "Turco-Sogdian", I remembered that Nicholas Sims-Williams and James Russell Hamilton had long ago collaborated on a book about Turco-Sogdian documents. I thought that their findings in that book would be a good place to embark on an investigation of the linguistic interaction between Sogdian and Turkic. So I asked Nicholas to say a few words describing the nature of the language of such documents, and maybe even give a fairly straightforward, simple example of such language?

The book is called Turco-Sogdian documents from 9th–10th century Dunhuang. It was first published in French as Documents turco-sogdiens du IXe–Xe siècle de Touen-houang on behalf of Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum by School of Oriental and African Studies, London, 1990 (WorldCat record). Nicholas explained to me:

It's hard to give a short description or a single example, as the term "Turco-Sogdian" covers a range of different combinations of the two languages, from the simple case of Turkish loanwords in a Sogdian text to the copying of syntactic features. The best study of the nature of the language is by Yutaka Yoshida in my [NS-W] Festschrift: “Turco-Sogdian features”, Exegisti monumenta. Festschrift in honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams (ed. W. Sundermann, A. Hintze, and F. de Blois), Wiesbaden, 2009, pp. 571-585, where you will find plenty of examples as well as excellent discussion of them.

Here are some selections from Yoshida's paper (pp. 571-572):

From the linguistic point of view, this material is quite unique in that the Sogdian dialect or variety found in it not only contains many Turkish names but also shows expressions based on Turkish idioms and constructions influenced by Turkish syntax. That is the reason why Sims-Williams and Hamilton called the language “turco-sogdien”. As a Sogdianist, I am absolutely certain that this unique variety of Sogdian written in horrible cursive script would not have been at all comprehensible without Sims-Williams’s profound insight and formidable competence in things Sogdian. In any case I greatly benefited from their results when I myself began to edit three Manichaean Sogdian letters (Letters A, B, and C) discovered at a ruined cave in Bäzäklik, Turfan.

While the idea that Uighur or Old Turkic influenced Sogdian was at that time quite new and astonishing, the opposite direction of influence had been taken for granted.2 Many Sogdian loanwords are found in Old Turkic and the long-standing symbiosis of the two peoples is widely attested in historical sources.3 Among other things, the so-called Uighur script is derived from the cursive variant of Sogdian script. Thus, the bulk of studies of the linguistic aspect of Sogdo-Turkish or Sogdo-Uighur language contact has been done by Turkologists rather than by Sogdianists.4 Here again Sims-Williams is an exception in that he made an important contribution to the elucidation of the process in which the Sogdian script was applied to the Uighur language, cf. Sims-Williams 1981.

Now that the influence in both directions has been recognized the time is ripe for the collaboration of Sogdianists and Turkologists to elucidate the realities of the linguistic contact between Sogdian and Old Turkic.5 In this paper I will confine myself to the analysis of the Turco-Sogdian texts, that is to say Sogdian texts showing strong Old Turkic influence, and try to collect and classify the features resulting from the contact. However, many of the features discussed in this paper have been noticed by Sims-Williams and Hamilton before and I shall just continue a little their groundbreaking researches.

In what follows I list those linguistic features which are most likely to represent Turco-Sogdian characteristics. However, we must always be prudent in our identification of such features as Turco-Sogdian, partly because our knowledge of Sogdian is still far from being sufficient to identify ‘genuine’ Sogdian. Moreover, it is also possible that several Turco-Sogdian features have been overlooked or not recognized as such by the present author, who is not a specialist of Old Turkic linguistics. In my discussion the Turco-Sogdian features are classified as follows:

(A) copying of idioms and collocations,

(B) copying of grammatical/functional morphemes,

(C) copying of non-finite constructions,

(D) code-switching and nonce loanwords, and

(E) pronunciation and spellings.

However, this classification is only for the sake of convenience and no consistency is claimed here. It must also be understood that due to the limited space available I have to confine myself to listing only one or two typical examples under each category.

What follows are the categories of Turco-Sogdian features that I [VHM] have extracted from pp. 573-581 of Yoshida's masterful article. Naturally, under each category he gives examples and analyses.

A-1 Idiomatic expressions

A-2 Epistolary formulae

A-3 Hendiadys and alliterative pairs

A-4 Copying of polysemy

B-1 x’t as a marker of the subjunctive

B-2 Enclitic pronouns placed after nouns

B-3 m’xt and šm’xt

B-4 Adpositions

C-1 Past participles

C-2 Absolutives

C-3 Others: -y forms, -’mnty βw-, and present infinitives

C-4 Isomorphism or metatypy

p. 572n4 Since virtually every Uighur text contains Sogdian loanwords, it is simply impossible to list all the publications discussing Sogdian elements in Uighur.

Yoshida's conclusion (p. 582) is especially telling:

Remarking on the Turco-Sogdian variety, Sims-Williams 1992, p. 56 states: “… the writers, even though they wrote in Sogdian, were more accustomed to thinking in Turkish”. R.M. Dawkins 1916, p. 198 describes the modern Greek language influenced by Turkish in a very similar way: “… the body has remained Greek, but the soul has become Turkish”. The description of the bilingual Sogdians living in Balāsāγān by Maḥmūd al-Kāšγarī in the 11th century is also very similar: “… They are from Soγd which is between Bukhara and Samarqand, but their dress and manner is that of Turks”, cf. Dankoff/Kelly, vol. I, p. 352. Apparently, those bilingual Sogdians resident in Balāsāγān were more accustomed to thinking and behaving in Turkish ways, just as the souls of some Greeks in modern Turkey became Turkish. The Turco-Sogdian texts discussed in this paper seem to betray the language of the Turkicized Sogdians living in the West Uighur Kingdom.30

Here we have linguistic interactions between languages of different families in the trenches. Not only is it clear that it actually happens, with scholars of the caliber of Nicholas Sims-Williams, James Russell Hamilton, and Yutaka Yoshida, it is proven beyond the shadow of a doubt.

Selected readings

- "Hellenism in East Asia" (12/4/22)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 7" (1/11/21) — with lengthy bibliography of pertinent works

- "Horses, soma, riddles, magi, and animal style art in southern China" (11/11/19) — details how the akinakes and other attributes of Saka / Scythian culture penetrated to the far south of what is now China; excessive sacrifices of horses in the south and in Shandong

- "Revelation: Scythians and Shang" (6/4/23) — has much to do with horse and human sacrifice and burials.

- "Of jackal and hide and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/16/18)

- "Horse culture comes east" (11/15/20)

[Thanks to Nicholas Sims-Williams; Xiuqin Zhou; June Teufel Dreyer; Sanping Chen; Gail Brownrigg; Katheryn Linduff; Paul Smith; Robert Harrist; Judith Lerner; Xinyi Ye]

Ron Irving said,

October 28, 2024 @ 1:48 pm

Crazily enough, I was at the Penn Museum two Fridays ago for the first time in close to 50 years and I was so taken by this horse relief that I took a photo of it. What fun to see it ten days later as the subject of your post.

Lucas Christopoulos said,

October 28, 2024 @ 9:11 pm

For the Horses of Eucratides (Εὐκρατίδης 172/171–145 BC), it s still the symbol of the Bank of Afghanistan today (Pashto: د افغانستان بان), with even the text ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ remaining there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Da_Afghanistan_Bank

bukwyrm said,

October 29, 2024 @ 3:07 am

marshal prowess = martial prowess?

Philip Taylor said,

October 29, 2024 @ 3:15 am

Or even "marital prowess" ?!

Victor Mair said,

October 29, 2024 @ 9:17 am

@Philip Taylor

That's ridiculous / silly.

Philip Taylor said,

October 29, 2024 @ 11:31 am

Agreed — it was intended as nothing more.

Pamela said,

October 29, 2024 @ 4:05 pm

Stupendous post. I'm not sure I'd turn a hair at the idea of a "Sogdian horse," since the Sogdians may have been descended from Skythian populations. Here the references seem to be the Sogdians on the western flank of the Turkic Khaghanate, but they may also have been conduits of Nisean horses, as with so many other aspects of Iranian culture and economy. But speaking of the horses, the names here are confusing. If I'm remembering right, the tag in the Penn museum says (or said) that the horse was "Snowcup," whatever that would be. I could see some possible identity with this "Autumn Dew," but is this among the names listed here for the six noble steeds?

Julian said,

October 29, 2024 @ 5:57 pm

Somewhat surprised by this statement:

'R.M. Dawkins 1916, p. 198 describes the modern Greek language influenced by Turkish in a very similar way: “… the body has remained Greek, but the soul has become Turkish"

But with a bit of googling found that he was actually talking about dialects of Cappadocia.