Archive for Language and food

August 29, 2022 @ 3:29 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and food, Lost in translation

Fantastic collection of Chinglish examples from WeChat.

There are 18 examples all together. I've already done 2 or 3 of them (see under "Selected readings" below), and a couple of them are not so great. That leaves around a dozen that are previously unknown and quite hilarious. I'll do them in two or three batches.

1.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 21, 2022 @ 11:36 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Animal communication, Etymology, Language and animals, Language and food, Language and history, Language and medicine, Onomatopoeia

A couple of days ago, we had occasion to come to grips with the word "garble": "Please do not feel confused" (8/19/22). This led Kent McKeever to write as follows:

Your recent use of "garble" has prompted me to pass on something I recently stumbled on. I have been poking at the digital files of the Newspapers of Eighteenth Century English newspapers and ran across a reference to the London city government position of "Garbler of Spices." From the context, it seems to be an inspector, perhaps processor, of spice imports. Totally new to me.

Totally new to me too.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 20, 2022 @ 12:43 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and archeology, Language and biology, Language and food, Names, Neologisms

A new kind of cabbage for me:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 1, 2022 @ 11:38 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and culture, Language and food

Many of us first learned about the Balkan red pepper sauce / relish / spread called "ajvar" in this post: "Bosnian menu" (7/28/22). Simplicissimus contributed a nice comment in which it was averred that the BCS (Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian) "word ‘ajvar’ and the English word ‘caviar’ both derive from the same etymon, the Ottoman Turkish word ‘havyar’ (which, in turn, derives from the Persian ‘xâvyâr’) — now that I think about it, it’s not unimaginable to me that ‘ajvar’ got its name on account of a vague resemblance to red caviar."

Since I was one of those who had not previously heard of ajvar but was quite familiar with caviar, Simplicissimus' remark really piqued my fancy because neither did the two food items in question resemble each other very much (fish roe vs. red pepper sauce), nor was the phonological resemblance that great (thinking especially of the "c" at the beginning of "caviar" and its absence from "ajvar"). So I decided to dig more deeply into the relationship between ajvar and caviar. Turns out to a fascinating linguistic, cultural, and culinary story.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

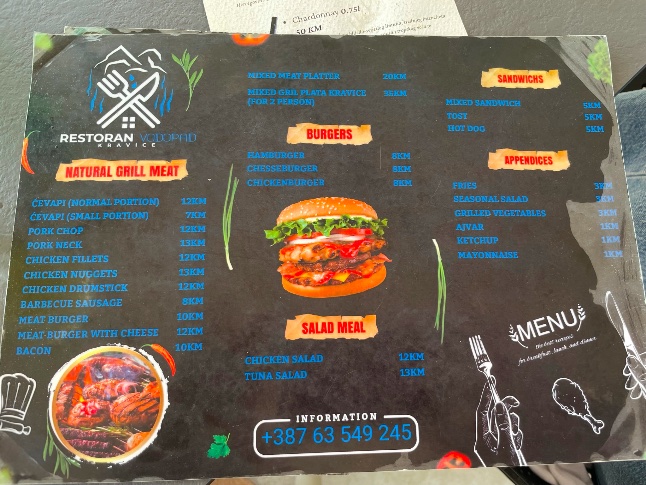

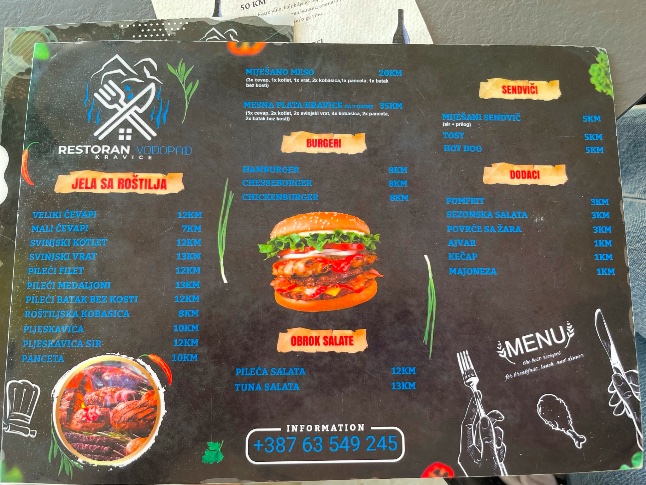

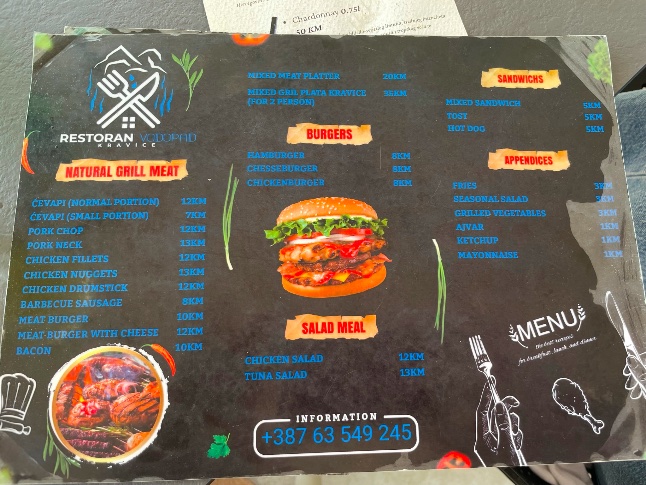

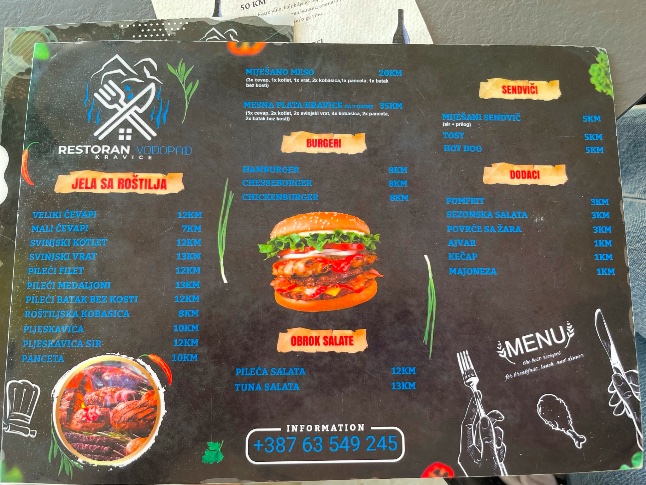

July 28, 2022 @ 12:06 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and food, Translation

Nick Tursi sent in this Bosnian menu from a cafe near Kravica waterfalls in Herzegovina:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

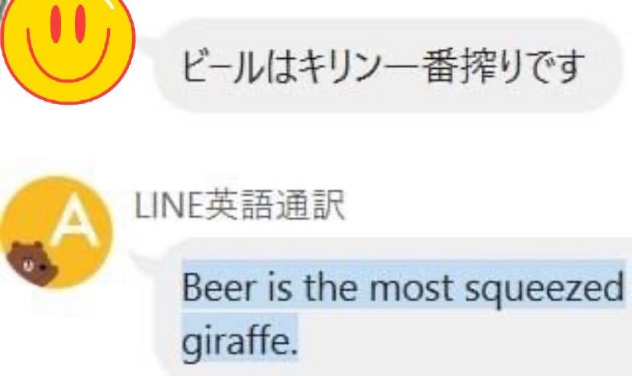

July 17, 2022 @ 8:39 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and advertising, Language and food, Lost in translation

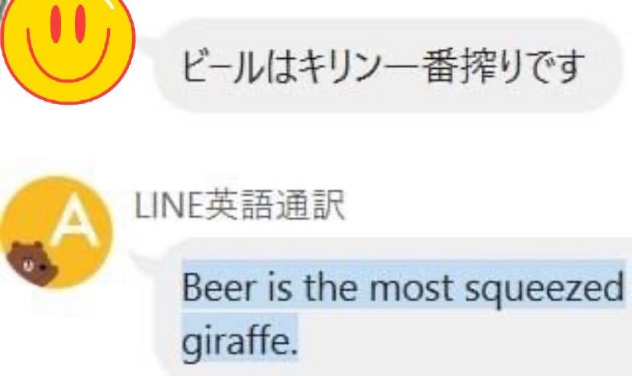

[This is a guest post by Nathan Hopson]

Today I bring you this cringey translation from the social networking app Line (developed in South Korea, very popular in Japan):

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 27, 2022 @ 9:48 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and culture, Language and food, Usage

Chopsticks: in cookery, designates:

a pair of thin sticks, of ivory, wood, etc, used as eating utensils by the Chinese, Japanese, and other people of East Asia

[C17: from pidgin English, from chop quick, of Chinese dialect origin + stick1]

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014

That's for the English word, now for the Chinese:

The Old Chinese words for "chopsticks" were zhù 箸 (OC *das) and jiā 梜 (OC *keːb). Zhù 箸 is preserved in almost all Min dialects (Taiwanese tī, tū; Fuzhou dê̤ṳ) and some other dialects, especially those in some contact with Min; it is also preserved in loans to other languages, e.g., Korean 젓가락 (jeotgarak), Vietnamese đũa and Zhuang dawh. Starting from the Ming Dynasty, the change to kuàizi 筷子 occurred in Mandarin, Wu, and some Cantonese dialects. The 15th century book Shuyuan Miscellanies (《菽園雜記》) by Lu Rong (陸容) mentioned this change:

-

-

- As the mariners feared 住 (“to stay”) […], they called zhù 箸 (“chopsticks”) kuàier 快兒 (lit. "quick + diminutive suffix"). [VHM: alt. "As the mariners had a taboo against "lingering / staying", they called zhù 箸 (“chopsticks”) kuàier 快兒 (lit. "quick + diminutive suffix").

The bamboo radical (zhu [the sound is not relevant here 竹) was later added to kuài 快 to form kuài 筷.

(source, with some additions by VHM)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 23, 2022 @ 8:27 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and food, Language and literature, Translation

Martin Delson sent in this interesting puzzler:

I'm participating in an international virtual book-club where all participants are bilingual in German and English. For some reason, the book that the group chose to read is Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori.

Wikipedia tells me the Japanese title is "Konbini ningen (コンビニ人間)".

A pair of sentences, not far into the book, reads as follows in the English translation

"The first at the cash register was the same little old lady who had been the first through the door. I stood at the till, mentally running through the manual as she put her basket containing a choux crème, a sandwich, and several rice balls down on the counter."

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 22, 2022 @ 6:10 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and food, Morphology

We've had two consecutive posts on oil-related words (see "Selected readings" below). julie lee made this comment on the first of the two:

Old Chinese/Old Sinitic *lew is similar in sound and meaning to Welsh OLEW "oil".

[From Middle Welsh olew, form Old Welsh oleu, from Proto-Brythonic *olew, from Vulgar Latin *olevum, from Latin oleum (“oil”).] (source)

julie's observation inspired me to ask Doug Adams whether there were any Tocharian words for oil. He replied:

There are two (sort of), There are both ṣalype and ṣmare. The first is 'oil (particularly sesame oil); salve, ointment' (also oil in a lamp), the second is, as a noun, 'oil' (as in a lamp) and, as an adjective, 'smooth, even, slippery.' The first is etymologically connected to English salve and the second to English smear.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 21, 2022 @ 4:47 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and culture, Language and food, Language and sports, Language and the law

In the previous post ("Oil: a partial paradigm" [6/19/22)]), we have been discussing the origins and ramifications of the derivation of the word "oil" from the ancient Greek word for olive. The last comment (before I wrote this post), by Coby, states: "Spanish also has the word óleo, which can mean either oil paint or the oil used in church rituals." Reading Coby's reference to óleo immediately sparked fond childhood memories of the Mair family ritual of mixing margarine.

We were a large and not well off family, so we seldom could afford real butter. Consequently, we used oleomargarine to spread on our bread rather than butter. We referred to it as "oleo" instead of "margarine", since the latter seemed too fancy-fussy in our household, and "oleomargarine" would have taken too much time to pronounce and would have been considered archly pedantic among us rural Ohio folk.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 19, 2022 @ 3:20 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Etymology, Language and food, Language and science

Oil is one of the most important substances used by human beings. It can be an essential food for consumption, a medium for cooking and frying, a lubricant, a material for the transmission of pressure through closed channels, a soothing substance for the skin, a substance to burn for propulsion and illumination, a polishing agent, and so forth. It can even be used metaphorically and literally to signify a calming agent:

The figurative expression pour oil upon the waters "appease strife or disturbance" is by 1840, from an ancient trick of sailors.

Another historical illustration which involves monolayers, was when sailors poured oil on the sea in order to calm 'troubled waters' and so protect their ship. This worked by wave damping or, more precisely, by preventing small ripples from forming in the first place so that the wind could have no effect on them. [J. Lyklema, "Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science," Academic Press, 2000]

The phenomenon depends on what are called Marangoni effects; Benjamin Franklin experimented with it in 1765.*

(source)

[*What did not excite the curiosity of the founder of the University of Pennsylvania?]

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 17, 2022 @ 7:47 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Animal behavior, Animal communication, Language and food, Language and medicine

[This is a guest post by Nathan Hopson]

If you’re Japanese, chances are it’s the latter.

Nekojita (猫舌 lit. “cat’s tongue”) is a phrase in Japanese most commonly used to describe people who can’t or don’t like to eat or drink hot things. The word means both the actual tongue itself and, by extension, a person with a cat’s tongue. In other words, it is a synecdoche.

The term is common in Japan, reflecting the fact that many people consider themselves to be/have cat tongues; in a 2018 survey of 10,000 Japanese of all ages, about half described themselves as nekojita. The results are summed up in the accompanying image, in which pink indicates those who answered yes to the question, “Are you nekojita?” As you can see, more than half of 10-49-year-olds consider themselves to have heat-sensitive tongues.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 11, 2022 @ 11:47 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and food, Language and literature, Proverbs

Received from Nathan Hopson:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink