Old Ukrainian windmills and Old Sinitic reconstructions

« previous post | next post »

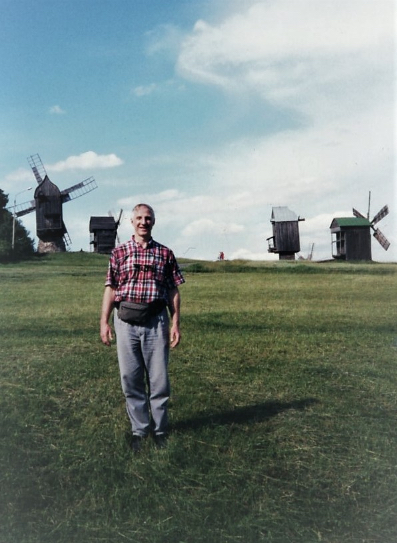

VHM somewhere in Ukraine, probably late summer 2002:

My sister sent the photo to me as a sort of birthday present. Since it came completely out of the blue, I felt a kind of dissociation, because the setting made me imagine that I was in Holland, but I couldn't remember standing in front of so many windmills in a field in Holland. As a matter of fact, I couldn't remember standing amidst so many windmills in a Ukrainian grassland.

I had always associated windmills with water — pumping it up from the ground, pumping it out from behind dikes and channels, which makes perfect sense for a place like Holland that is almost under water (remember the little Dutch boy who stuck his finger in a leaky dike and saved the Netherlands / Nederland). I just wasn't programmed to think of windmills being used for other purposes. To me, they were quintessentially Dutch — windmolen — but seeing the word written that way made me think of milling wheat, which we have posted about several times on Language Log (see "Selected readings").

More than three thousand years ago, the archaic character for "wheat" (mài 麥) was used to write the word for "come" (lái 來) because they sounded alike.* While we now know that the agricultural crop did come to East Asia from the west, it's an entirely different matter whether the Sinitic word itself was borrowed from a western source, which may or may not be the case. Nearly three decades ago, I wrote a very long and detailed proposal for considering the Sinitic word mài 麥 ("wheat") as having been derived from an Indo-European source. This is on pp. 36b-38a of "Language and Script: Biology, Archaeology, and (Pre)History," International Review of Chinese Linguistics, 1.1 (1996), 31a-41b.

*mài 麥 ("wheat")

lái 來 ("come")

One doesn't have to be a philologist to notice the resemblance between the shapes (only the top part of 麥 [the bottom part is likely for the purpose of distinguishing the derived form 麥 from the original form 來]) of the two characters (the vertical stalk, the spreading roots, and the dangling tassels / leaves / ears / spikes) and their sounds (respectively):

- (Baxter–Sagart): /*m-rˤək/

- (Zhengzhang): /*mrɯːɡ/

(source)

- (Baxter–Sagart): /*mə.rˤək/, /*mə.rˤək/

- (Zhengzhang): /*m·rɯːɡ/

(source)

The simpler glyph, 來, pictographically represented "wheat". When the need was felt for a glyph to represent the homonymous, abstract, verbal notion of "come", 來 was retained for that purpose, while 麥 was devised by the addition of the extra squiggle at the bottom for the nounal meaning of "wheat".

These reflections on sounds and shapes (phonetic and semantic resemblances) of 來 / 麥 long ago (at least four decades) led me to the conclusion that

- (Baxter–Sagart): /*m-rˤək/

- (Zhengzhang): /*mrɯːɡ/

- (Baxter–Sagart): /*mə.rˤək/, /*mə.rˤək/

- (Zhengzhang): /*m·rɯːɡ/

were related to Indo-European mele-.

To crush, grind; with derivatives referring to various ground or crumbling substances (such as flour) and to instruments for grinding or crushing (such as millstones). Oldest form *melh2‑.

Full-grade form *mel‑. meal1, from Old English melu, flour, meal, from Germanic suffixed form *mel-wa‑.

meunière, mill1, mola2, molar2, mole4, moulin; emolument, immolate, ormolu, Latin molere, to grind (grain), and its derivative mola, a millstone, mill, coarse meal customarily sprinkled on sacrificial animals;

possible suffixed form *mel-iyo‑. mealie, miliary, milium, millet; gromwell, from Latin milium, millet.

Zero-grade form *ml̥‑. amylum, mylonite, from Greek mulē, mulos, millstone, mill.

Possibly extended form *mlī‑. blini, blintz, from Old Russian blinŭ, pancake.

[Pokorny 1. mel- 716]

(source) — listing relevant derivatives only

So what is the word for "windmill" in Ukrainian? According to Renata Holod, those structures in the photograph at the top of this post are called "mlyn", plural "mlyny", which is the word for "mill". The Ukrainian edition of Wikipedia tells us that "windmill" in Ukrainian is "vitryak [вітряк]" or vitryanyy mlyn [вітряний млин]", i.e., wind driven mill.

The first practical windmills were panemone windmills, which employed sails that rotated in a horizontal plane around a vertical axis and were used to grind grain or draw up water. They were acknowledged in the Middle East during the mid-7th century (based on a Persian source) and recorded in a Persian text of the 9th century as being used in Eastern Iran and Western Afghanistan.

Selected readings

- "Of shumai and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (7/19/16)

- "Words for cereals" (7/27/16)

- "Pulled noodles: Uyghur läghmän and Mandarin lāmiàn" (8/8/14)

[Thanks to Heidi Mair]

David Marjanović said,

March 27, 2022 @ 4:50 pm

That would have to be a very early loan to reflect the *h₂ [χ] as *k, quite a bit earlier than Proto-Tocharian.

But that's the only objection I can find. How has wheat been called in other languages around northern China?

Chris Button said,

March 27, 2022 @ 9:55 pm

Pulleyblank (1975) compares 磨 *mál "grind" with Proto-Indo-European *melh₂- "grind". The correspondence could be coincidental.

The uvular fricative for the laryngeal -h2 in *melh₂- does make things interesting since 來 originally ended in a voiced velar fricative -ɣ corresponding with the -k in 麥. Then again, that would fit better with the PIE -h3 laryngeal, although I would favor uvular -ʁ over -ɣ (as I would uvular -χ over velar -x for -h2).

I find Blažek‘s attempt to compare the Celtic form behind Old Irish mraich “malt” and other derivatives with 麥 to be very compelling. The phonology is more persuasive.

There’s also the Japanese reading mugi, which is tempting to associate as well.

Jens Østergaard Petersen said,

March 28, 2022 @ 3:50 am

On the (supposed) “squiggle”:

In the same issue of International Review of Chinese Linguistics that your own article appeared in, Pulleyblank has a note on 來/麥. I do not have access to the issue in question, but Pulleyblank refers to it in “Ji 姬 And Jiang 姜 – The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity,” Early China, Vol. 25 (2000), p. 23, n. 65. He writes:

“One indication that Shang writing as we know it must have had a prehistory is the relation between the graphs for lai 來 "come" and mai 麥 "wheat." The simpler graph for "come" is clearly based on a drawing of a plant while that for "wheat" has the addition of a graph for "foot." The obvious inference is that the simpler graph was originally created to write the word for "wheat" and was then borrowed, with the addition of the "foot" element, for the verb "come" because of similarity in pronunciation. But lai "come" was much more frequent than mai "wheat" so in the course of time the simpler graph was used for the verb and the more complex graph was used for the noun even though the "foot" signific was inappropriate. When, exceptionally, the graph 來 appears in the Shijing in a context that implies that it is a kind of grain, traditional commentary reads it as lai and interprets it as "a kind of wheat" (mai 麥) instead of recognizing it as the original graph for mai (“wheat”).

Jens Østergaard Petersen said,

March 28, 2022 @ 5:55 am

Another take on this: In early China, the idea that Heaven had bequeathed wheat on the Zhou was expressed in many places. Behind this may be the realization that wheat was not indigenous to China, wherefore wheat was called “what-has-come.”

For an elaboraiton of this interpretation, see Li Yu 李裕 – 《說文》來、麥之釋及其學術與文獻價值.武漢大學學報(哲學社會科學版)1995-02; against it, see Zhu Lanzhi 朱蘭芝 – 「來」「麥」之辨——兼及「麥自外來」說.山東行政學院學報2020-04.

AntC said,

March 28, 2022 @ 5:59 am

"Lewis assigns the date of the invention of the horizontal-wheeled mill to the Greek colony of Byzantium in the first half of the 3rd century BC, and that of the vertical-wheeled mill to Ptolemaic Alexandria around 240 BC." — that is, water-powered mills for grinding grain.

'Watermill' is ambiguous: a mill for pumping water/drainage? Or a mill for grinding, powered by water. (In C18/19th Britain, brick-built windmills and watermills with iron machinery were used for grinding all manner of stuff, including rock for cement and road surfaces.)

Blažek‘s attempt to compare the Celtic form behind Old Irish mraich …

"In recent years, a number of new archaeological finds has consecutively pushed back the date of the earliest tide mills, all of which were discovered on the Irish coast: A 6th century vertical-wheeled tide mill was located at Killoteran near Waterford."

(I became a windmill nerd after holidaying in Norfolk, where there are windmills for drainage all over the Fens and Broads. The technology was imported from the Holland.)

Kate Bunting said,

March 28, 2022 @ 11:54 am

As AntC says, most British people would associate windmills primarily with grinding grain, though I know they were widely used for pumping water in East Anglia. I've never heard of one of these being called a watermill; AFAIK the term is reserved for water-powered mills.

David Marjanović said,

March 28, 2022 @ 8:25 pm

…So this use of "-mill" for buildings that aren't mills is how wind power plants came to be called "windmills" in the US. I was wondering!

Chris Button said,

March 28, 2022 @ 9:08 pm

The Celtic origin of Old Irish mraich “malt” is apparently *mraki-

Old Japanese muᵑgi "wheat" would conventionally go back to munki. A 2013 article by Andrii Ryzhkov compares Proto Tungusic *murgi "barley".

Apparently there is Ryukyuan evidence that munki was monki, reflecting the merger of Proto-Japonic "o" with "u" (compare 瓜 uri from ori "melon"–presumably ultimately related to Old Chinese 瓜 *qraɣː from Arabic qar'a). Unfortunately that doesn't really help Ryzhkov's proposal.

He only comments that he can't at present find a suitable Indo-European comparison.

Philip Anderson said,

March 29, 2022 @ 2:44 am

Even in the Netherlands, I assume that windmills were used for milling originally, and only later used to drive pumps; the Dutch brought that technology to East Anglia, but windmills were in use in England before then.

Welsh ‘brag’ (malt) and its derivatives are cognate with Irish ‘mraich’, and not related to ’brew’.

Weituo said,

March 31, 2022 @ 10:46 am

I have grown used to VHM's dissections for Language log and appreciate the adding of bits here and there, as in 來 and 麥, but I have to say that the paragraph about "the first practical windmills" being "panemone" windmills sent me scurrying for the Shorter Oxford, because the word went against the grain, if you'll pardon the mixed metaphor. I don't possess a Lewis and Short, but, having been born in the shadow of the Tower of the Winds (Radcliffe Observatory), it seemed to me that panemone was a travesty, since it surely should have been pananemone, i.e. παν + ανεμοσ. Now where is Professor Mair to make the cut with his linguistic scalpel? The great god Pan would surely be displeased to be reduced to a mere 'p', but how can Zephyr or Boreas blow properly without that initial 'an' ?

Incidentally, for a Chinese imperial watermill in full working order, driven by a horizontal turbine, with transport, weighing, recording, sifting and grinding of the grain to the final soft peaks of flour, see the late tenth-century painting in the Shanghai Museum: Liu Heping "The Watermill and Northern Song Imperial Patronage of Art, Commerce and Science" The Art Bulletin (2002) 566-595.

AntC said,

March 31, 2022 @ 5:40 pm

Even in the Netherlands, I assume that windmills were used for milling originally, and only later used to drive pumps;

Yes, there's a technological reason: wind directions are unreliable (unlike the Mediterranean diurnal winds); you have to be able to turn the mill to face the wind. Until C17th this was achieved by including all the milling machinery in a housing with the sails, and balancing the whole lot on a post around which the miller turned it. I think those are all 'post mills' behind Victor in the photo — the fixed base/rotatable superstructure is particularly clear in the leftmost one. The post, supports, mill frame, sails were all made from wood — remarkable carpentry, derived from shipbuilding of course.

The water channels/pump are external to the mill: how to get a power drive out from a rotatable structure? The answer was to drill a hole vertically down through the post, then a drive shaft through that to gearing underneath that could lead to the pump — all of which had to be steel. So we're at the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Johannes said,

April 5, 2022 @ 4:31 am

Pretty probable that Japanese Kun'yomi reading mugi came from Old Chinese, as Cantonese still pronounce "麥" as [mAk] (rhymes with English 'muck').

Japanese On'yomi reading [baku].

One of those ooooold plants that came from the continent like bamboo 竹 [take] & [chiku]

Chris Button said,

April 6, 2022 @ 9:54 am

竹 “take” has been proposed as one of those pre-Sino Japanese early loans into Japanese as well. Although, the phonology seems more problematic than with 麥 “mugi”.

Chris Button said,

April 7, 2022 @ 11:06 am

On 竹, Old Chinese reconstructions with -uk tend to be the major issue, but they are misleading. A phonologically more accurate reconstruction (-uk could occur as one possibility of a surface realization) would be -əkʷ or -əq (the latter merging with the former). A correspondence of -əq with old Japanese -ak- is much easier to justify.