Archive for Translation

Translated abstracts and titles

There are many different subfields in Chinese Studies: religion (Buddhism, Daoism, Islam…), art history, archeology, anthropology, language, literature, linguistics, esthetics, philosophy, economics, ethnology, and so forth. Each of these subfields requires specialized knowledge and command of the requisite terminology. One cannot expect a generalist to be adequately equipped to deal with all of them.

Read the rest of this entry »

"…direction…"

The word direction is common in the English versions of the "operational updates" from the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine . For example, from the August 6 update:

In the direction of Bakhmut, the enemy from tanks, barrel and jet artillery shelled the areas of the settlements of Bakhmutske, Toretsk, Bilohorivka, Krasnopolivka, Pivnichne and Vershyna.

It led offensive battles in the direction of Yakovlivka-Vershyna and Kodema-Zaitseve, it was unsuccessful and left.

Leads an offensive in the direction of Bakhmut, hostilities continue.

It led an offensive in the direction of Lozove-Nevelske, was unsuccessful, withdrew.

Read the rest of this entry »

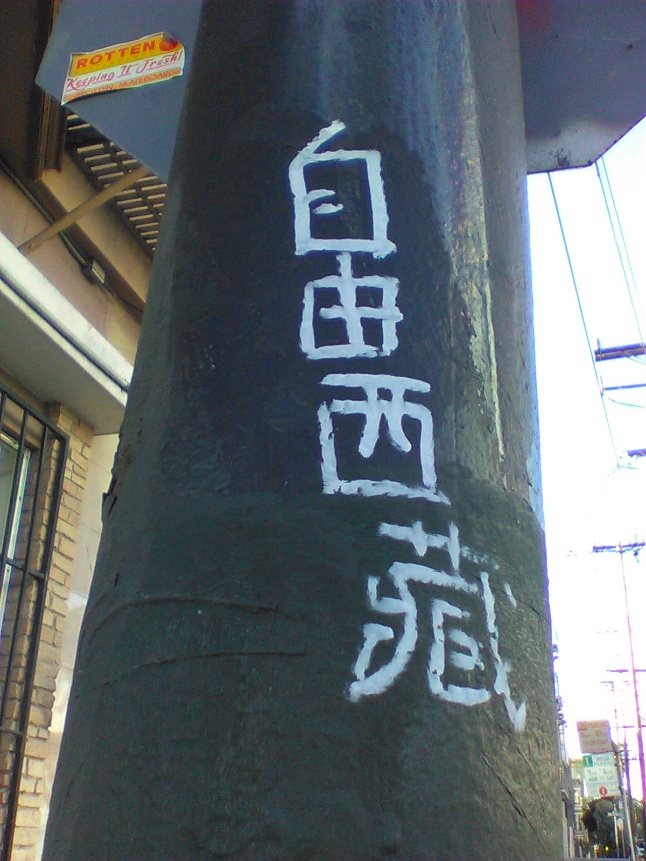

Free Tibet!/?

From Charles Belov: seen on a street-sign pole in the Mission District of San Francisco:

Read the rest of this entry »

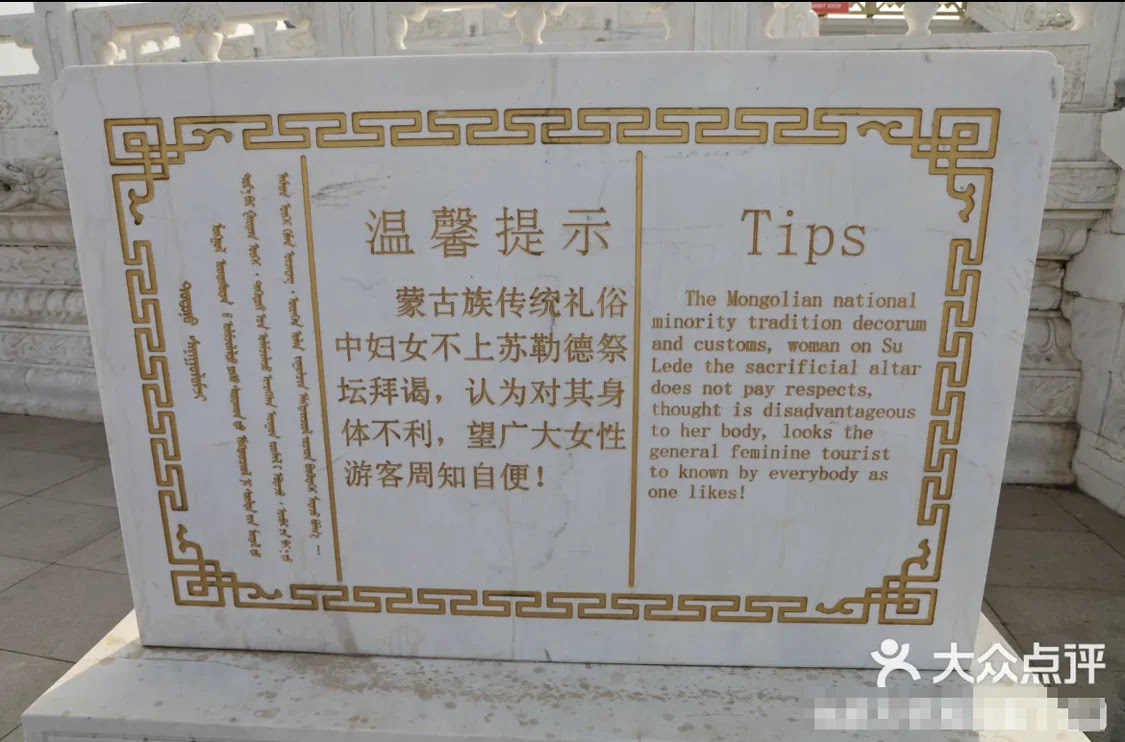

Gentle reminder for women who approach the cenotaph of Genghis Khan

Trilingual tablet at the altar of Genghis Khan (ca. 1162-1227) in Kandehuo Enclosure in the town of Xinjie, in the Ejin Horo Banner in the Ordos Prefecture of Inner Mongolia:

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »

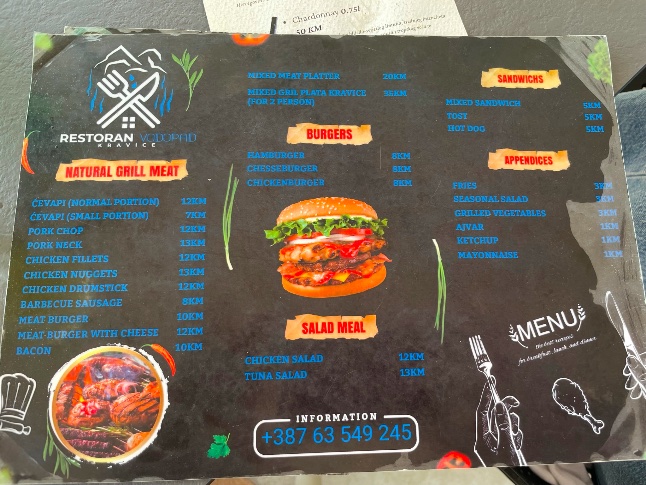

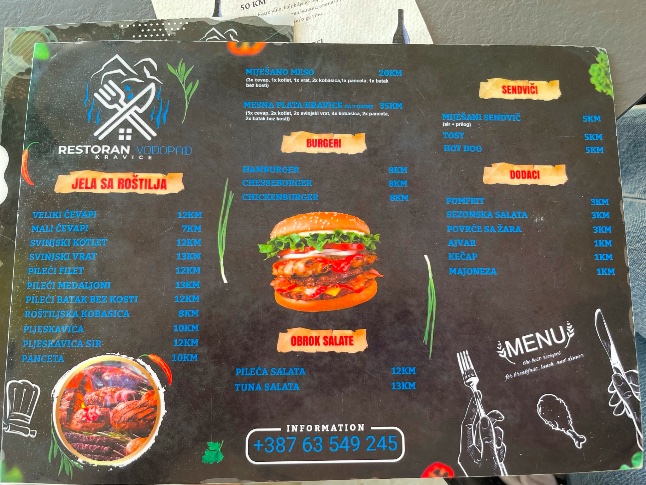

Bosnian menu

Nick Tursi sent in this Bosnian menu from a cafe near Kravica waterfalls in Herzegovina:

Read the rest of this entry »

Test-taking mentality and class society

Latest article in SupChina:

"‘Small-town test taker’ — phrase of the week"

A “small-town test taker” is a self-deprecating — or slightly insulting — phrase to describe a country bumpkin who works their butt off in pursuit of success.

Andrew Methven (7/22/22)

One would not expect a strongly class consciousness and behavior in a presumably classless communist society, but that seems to be the case in the PRC, especially in the entertainment sector, of all places.

Our phrase of the week is: small-town test taker (小镇做题家 xiǎo zhèn zuò tí jiā).

Context

Chinese pop singer Jackson Yee (易烊千玺 Yì Yángqiānxǐ) and two other celebrities are facing controversy after the National Theatre of China (国家话剧院 guójiā dà jùyuàn) hired them as staff performers, sparking calls on social media for more transparency amid concerns that they gained privileged access.

Read the rest of this entry »

Translation of multiple languages in a single novel

New York Times book review by Sophie Pinkham (6/21/22):

The Thorny Politics of Translating a Belarusian Novel

How did the translators of “Alindarka’s Children,” by Alhierd Bacharevic, preserve the power dynamics between the book’s original languages?

A prickly dilemma for a translator if ever there were one. Faced with a novel that is written in more than one language, how does one convey to the reader the existence and essence of those multiple languages? Because of the linguistic intricacies posed by the original novel and the complicated solutions to them devised by the translators, which are described in considerable detail and critically assessed by Pinkham, I will quote lengthy passages from the review (which may not be readily available to many Language Log readers), focusing almost entirely on language and translation issues.

Every bilingual country is bilingual in its own way. The principal languages in Belarus, which was part of the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union, and which remains in Russia’s grip, are Russian and Belarusian. Russian is the language of power, cities and empire; Belarusian is the language of the countryside, the home, the nation. In neighboring Ukraine, whose history in some ways resembles that of Belarus, Ukrainian is now the primary language. Belarusian, meanwhile, is classified by UNESCO as “vulnerable.”

Translators of novels written for bilingual readers thus face a daunting challenge: how to transplant a text clinging fast to its country of origin while preserving the threads of history and power between its original languages.

Read the rest of this entry »

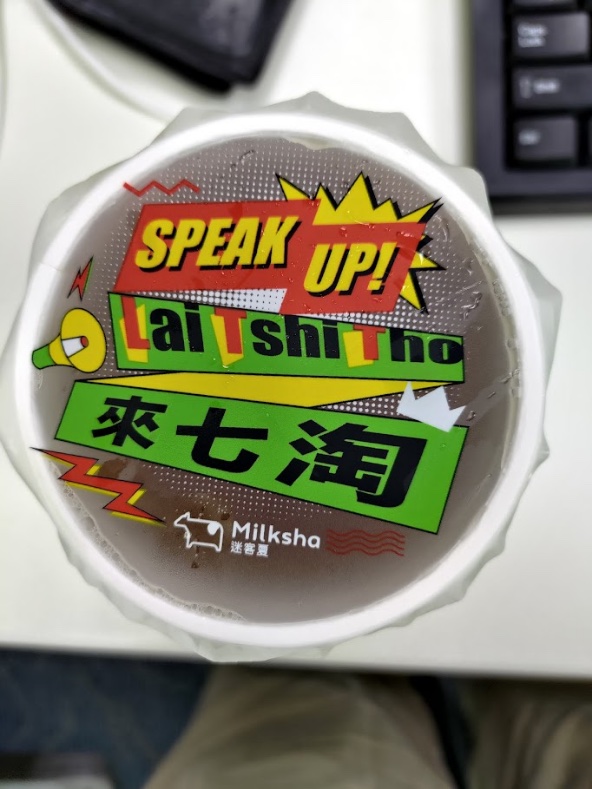

"You bear lost person": writing Taiwanese

From Mark Swofford, a cup of bubble tea with Taiwanese on it (romanized, Hanzified, and translated).

Read the rest of this entry »

Orthographic-crosslingual pun

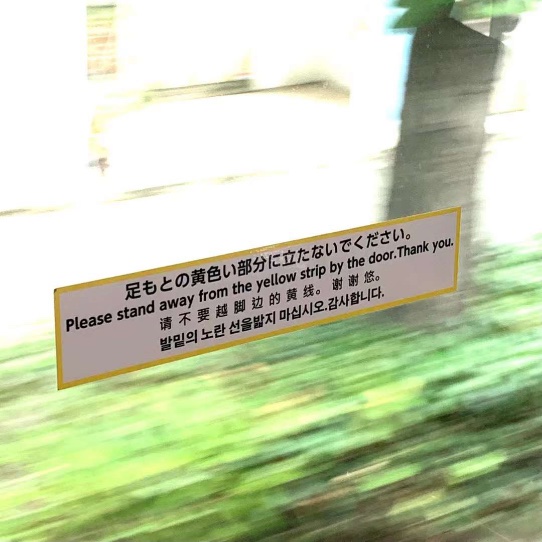

Xiaowan Cai received this picture from a friend of hers who is on exchange from Oxford University at Kyoto University. Everything in all four languages on the sign looks pretty normal, except that there is a not easily detectable, extraordinary gaffe — or ingenious tour de force — in the Chinese.

Read the rest of this entry »

Of cream puffs and shoe polish

Martin Delson sent in this interesting puzzler:

I'm participating in an international virtual book-club where all participants are bilingual in German and English. For some reason, the book that the group chose to read is Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori.

Wikipedia tells me the Japanese title is "Konbini ningen (コンビニ人間)".

A pair of sentences, not far into the book, reads as follows in the English translation

"The first at the cash register was the same little old lady who had been the first through the door. I stood at the till, mentally running through the manual as she put her basket containing a choux crème, a sandwich, and several rice balls down on the counter."

Read the rest of this entry »

Mi experiencia como Team Leader de compras vecinales

[This is a guest post by Conal Boyce]

[VHM: watch as much or as little of this 24-minute video as you wish; the most pertinent portion runs from 2:17 to 3:40]

Read the rest of this entry »