Archive for Writing systems

Phonology and orthography in Ming China

New book from Columbia University Press:

The Culture of Language in Ming China: Sound, Script, and the Redefinition of Boundaries of Knowledge

$35.00 £28.00

Publisher's description:

The scholarly culture of Ming dynasty China (1368–1644) is often seen as prioritizing philosophy over concrete textual study. Nathan Vedal uncovers the preoccupation among Ming thinkers with specialized linguistic learning, a field typically associated with the intellectual revolution of the eighteenth century. He explores the collaboration of Confucian classicists and Buddhist monks, opera librettists and cosmological theorists, who joined forces in the pursuit of a universal theory of language.

Read the rest of this entry »

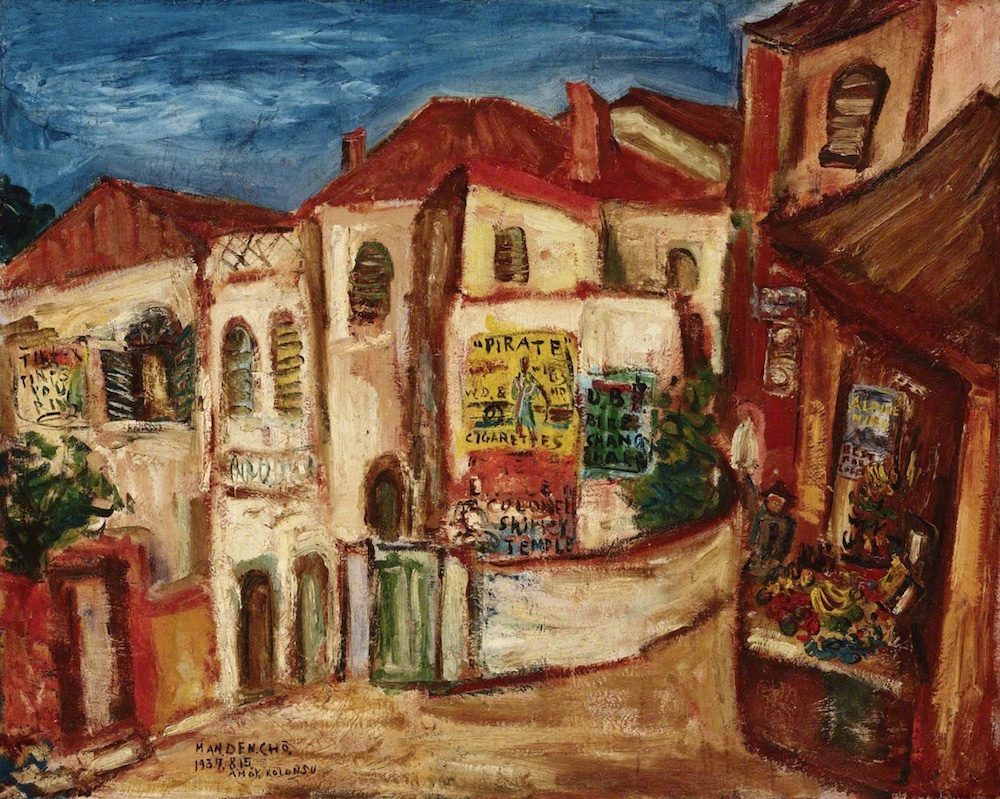

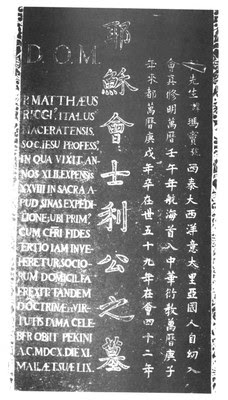

Matteo Ricci's tombstone

Epigraph on the Tombstone of Matteo Ricci in the Zhalan Cemetery in Beijing:

Inscription on the tomb of Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), black-and-white photograph, unknown photographer; source: with the kind permission of the Ricci Institute, University of San Francisco.

Read the rest of this entry »

Morphemes without Sinographs

Commenting on "Educated (and not so educated) guesses about how to read Sinographs" (11/16/21), Chris Button asked:

I’m curious what you mean by “pseudo explanation”? The expected reflex from Middle Chinese times is xù, but yǔ has become the accepted pronunciation based on people guessing at the pronunciation in more recent times. Isn’t that a reasonable explanation?

To which I replied:

It's such a gigantic can of worms that I'm prompted to write a separate post on this mentality. I'll probably do so within a few days, and it will be called something like "Morphemes without characters".

Stay tuned.

Read the rest of this entry »

"They're not learning how to write characters!"

So exclaimed a graduate student from the PRC. She was decrying the new teaching methods for Mandarin courses in the West that do not emphasize copying characters countless times by hand and taking dictation (tīngxiě 聽寫 / 听写) tests, but rather relying on Pinyin (alphabetical) inputting to write the characters via computers.

These are topics we have discussed numerous times on Language Log (see "Selected readings" below for a sample of some of the posts that touch on this subject. I told the student that this is indeed a fact of life, and that current teaching methods for Mandarin emphasize pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, sentence structure, etc., and that handwriting the characters is no longer a priority. Whereas in the past handwriting of the characters used to take up over half of a student's learning time, now copying characters is reduced to only a small fraction of that.

Read the rest of this entry »

Mixed Mandarin-Taiwanese-Japanese orthography

Writing Mandarin phrases with Roman letter acronyms

Since the vast majority of inputting in the PRC is done via Hanyu Pinyin, netizens are thoroughly familiar with the alphabet and use it regularly as part of the Chinese writing system.

One common usage for the alphabet in the PRC is acronymically to designate frequently encountered Mandarin phrases. In "The Chinese Internet Slang You Need to Know in 2021", CLI (10/19/21), Anias Stambolis-D'Agostino introduces six popular online acroyms:

1. yyds (永远的神)

永远的神 (yǒngyuǎn de shén; yyds) means “eternal God” and describes an outstanding person or thing. It's similar to the saying GOAT (Greatest of All Time) in English. The phrase is often used by fans to praise their idols or simply to describe something they are fond of.

For example:

-

- 桂林米粉太好吃了,桂林米粉就是yyds!

- Guìlín mǐfěn tài hàochī le, Guìlín mǐfěn jiùshì yyds.

- Guilin rice noodles are delicious, they’re just yyds!

Here's another example:

-

- 李小龙的中国功夫太厉害了,他就是yyds!

- Lǐxiǎolóng de Zhōngguó gōngfū tài lìhài le, tā jiùshì yyds

- Bruce Li’s kung fu skills are so good, he’s such a yyds!

Read the rest of this entry »

New expressions for karaoke: the phoneticization of Chinese

My first acquaintance with the word "karaoke" was back in the 1980s, when I was visiting my brother Denis, who was then a translator for Foreign Languages Press in Beijing. He lived in the old Russian-built Friendship Hotel, a very spartan place compared to today's luxury accommodations in big Chinese cities. There wasn't much unusual, interesting, or attractive about the place (though they had bidets in the bathrooms, as did many other Russian style accommodations in China at that time), but I was deeply intrigued by a small sign at the back of one of the buildings that led to a basement room. On it was written "kǎlā OK 卡拉OK". The best I could make of that novel expression was "card pull OK," and I thought that it might have something to do with documentation. I asked all my Chinese scholar friends what this mysterious sign meant, but not one of them knew (remember that this was back in the mid-80s). It was only when I returned to the United States that I realized kǎlā OK 卡拉OK was the Chinese transcription for Japanese karaoke. It took a lot more time and effort before I figured out that karaoke is the abbreviated Japanese translation-transliteration of English "empty orchestra," viz., kara (空) "empty" and ōkesutora (オーケストラ). When I reported this to my Chinese linguist friends (Zhou Youguang, Yin Binyong, and others) back in Beijing the next year, they were absolutely flabbergasted. They had been convinced that the OK was simply the English term meaning "all right," but they had no idea what to make of the kǎlā portion.

Read the rest of this entry »

Simplified characters defeat traditional characters in Ireland

Article by Colm Keena in The Irish Times (8/2/21):

"Decision on Mandarin Leaving Cert exam ‘outrages’ Chinese communities:

Exam subject that students can sit from 2022 will only allow for simplified Chinese script"

Here are the first four paragraphs of the article:

Chinese communities in Ireland are “outraged” by the decision of the Department of Education to use only a simplified script in the new Leaving Certificate exam in Mandarin Chinese, according to a group set up to campaign on the issue.

The new exam subject, which students can sit from 2022, will not allow for the use of the traditional or heritage Chinese script, which is used by most people from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other, mostly non-mainland-China locations.

The decision by the department is a “discrimination against the heritage Chinese learners in Ireland,” according to Isabella Jackson, an assistant professor of Chinese history in Trinity College, Dublin, who is a member of the Leaving Cert Mandarin Chinese Group.

“It is wrong for our Irish Government to deny children of a Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau background the right to sit an examination using the Chinese script that is part of their heritage.”

Read the rest of this entry »

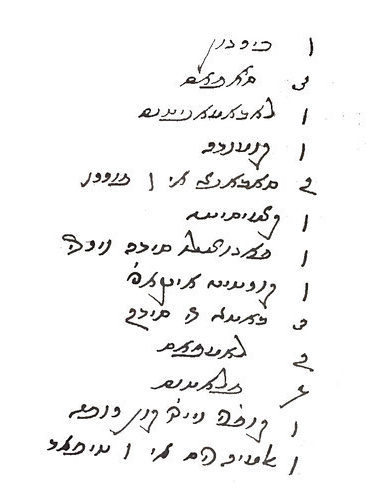

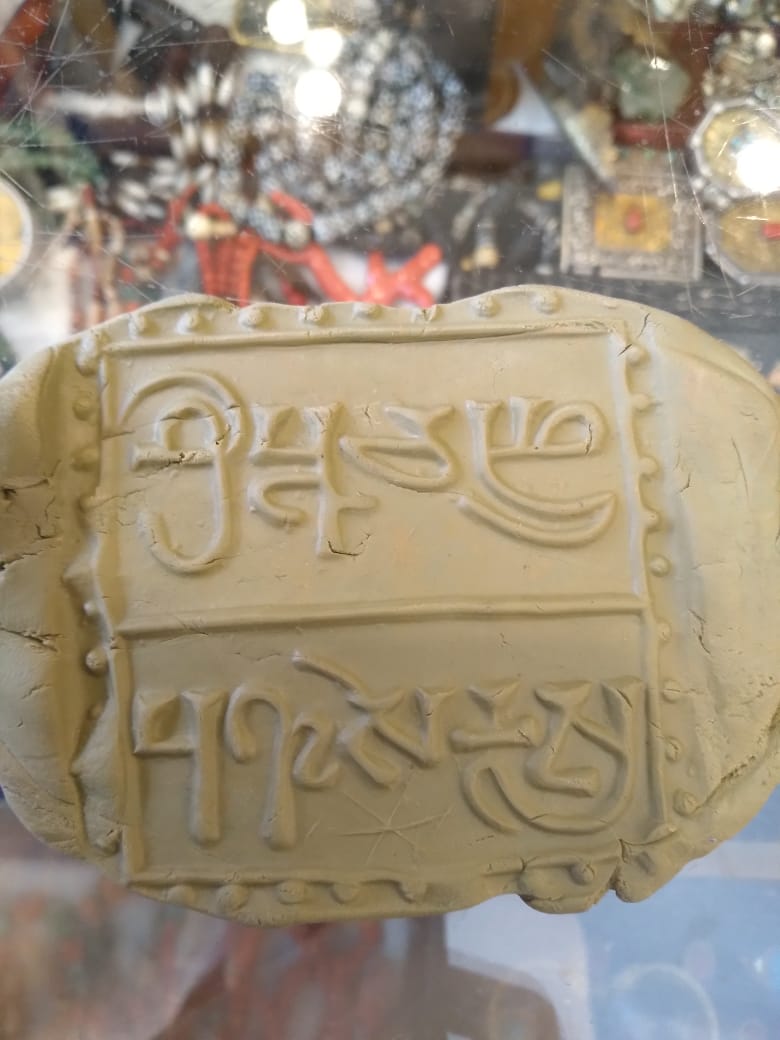

Unusual Sarada inscription

The following are photographs of a supposedly Śāradā / Sarada / Sharada inscription, sent to me by an anonymous correspondent:

Read the rest of this entry »