Kana, not kanji, for names

« previous post | next post »

From Greg Ralph:

Greg explains:

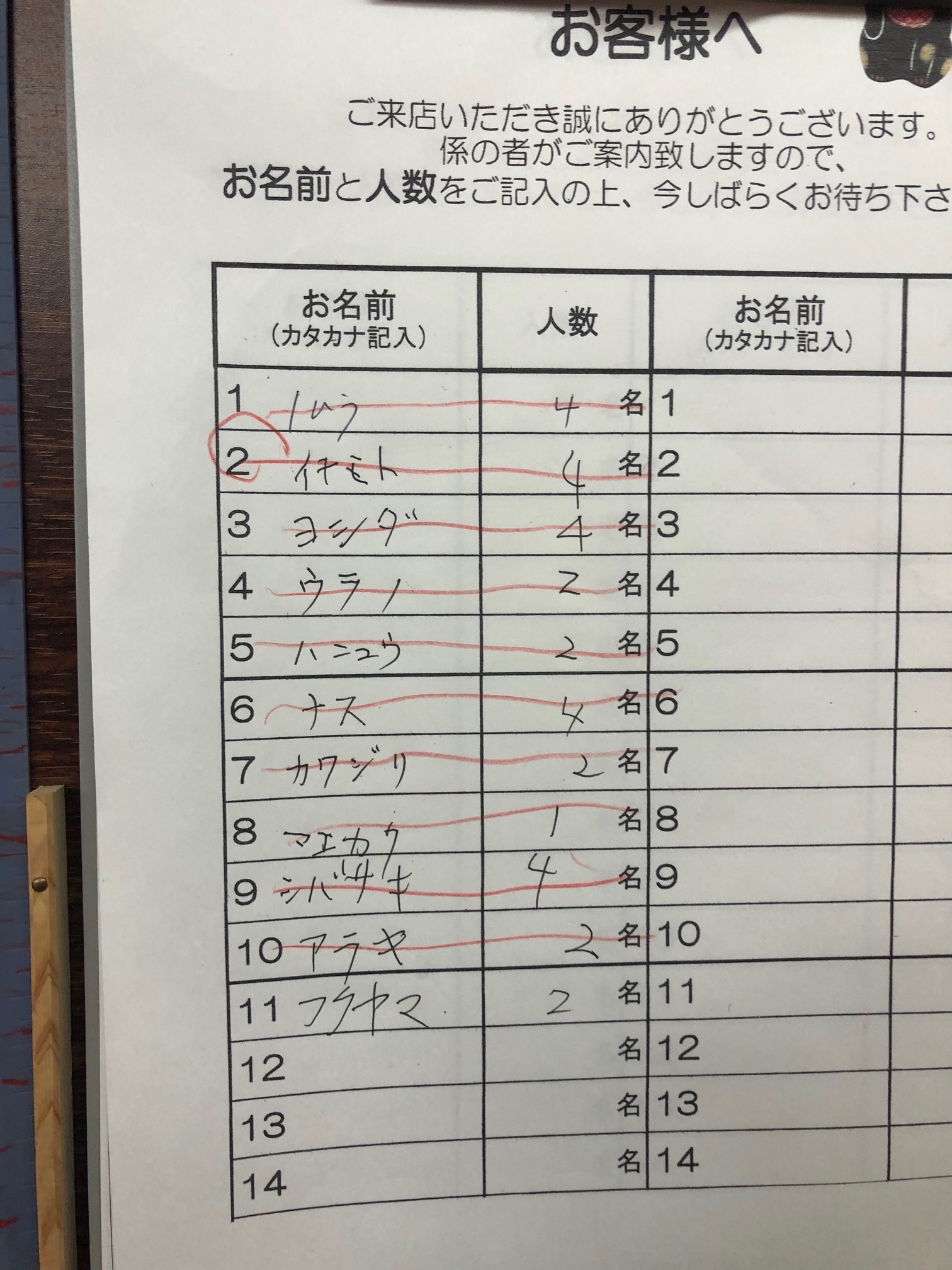

I thought you might be amused by this. Obeying the Japanese custom of eating toshikoshi soba 年越しそば*, soba for the New Year, we queued at our favourite local restaurant. It’s popular and at busy times like New Year you have to write your name, then wait near the door so that the staff can call you when there is a table.

On several successive pages name after name in katakana only. After all – if someone wrote their name in kanji, the staff might have no idea how to pronounce it, the vagaries of Japanese nanori** readings being what they are. Image of one page above.

Notes

*Toshikoshi soba (年越し蕎麦), "year-crossing noodle", is Japanese traditional noodle bowl dish eaten on New Year's Eve (31 December). This custom lets go of hardship of the year because soba noodles are easily cut while eating.

(source)

**Nanori (名乗り, "to say or give one's own name"; also, by extension "self-introduction") are kanji character readings (pronunciations) found almost exclusively in Japanese names.

In the Japanese language, many Japanese names are constructed from common characters with standard pronunciations. However, names may also contain characters which only occur as parts of names. Some standard characters also have special pronunciations when used in names. For example, the character 希, meaning "hope" or "rare", usually has the pronunciation ki (or sometimes ke or mare). However, as a female name it can be pronounced Nozomi.

In compounds, nanori readings can be used in conjunction with other readings, such as in the name Iida (飯田). Here, the special nanori reading of 飯 (いい, ii) and a standard kun'yomi reading of 田 (だ, da) are combined. Often (as in the previous example), the nanori reading is related to the general meaning of the kanji, as it is frequently an old fashioned way to read the character that has since fallen into disuse.

(source)

As I mentioned in a post several years ago, one of the hardest parts of my training as a Sinologist was learning how to Romanize Japanese proper nouns correctly. I've also several times mentioned that, over the years since I began travelling to Japan, katakana are increasingly used with a higher proportion in relation to kanji, even for personal names (as on plaques for one's house or office) and other proper nouns. And I've noted that one of the first acts of a new session of the Japanese diet, so I am told, is to make sure that everyone knows how each other's name is pronounced.

Selected readings

- "Japanese readings of Sinographic names" (9/26/18)

- "Sino-Japanese" (7/2/16)

- "More katakana, fewer kanji" (4/4/16)

- "Japanese survey on forgetting how to write kanji" (9/24/12)

- "Japanesespanishmackerel " (11/13/13)

- Victor H. Mair, ed., ABC Dictionary of Sino-Japanese Readings; Series: ABC Chinese Dictionary Series (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2016).

Neil said,

January 3, 2021 @ 5:01 pm

I thought katakana was used to transcribe foreign words. Why wouldn’t everyone have written their names in hiragana? I don’t know too much about Japanese, so please excuse what might be a facile question.

david said,

January 3, 2021 @ 5:10 pm

@Neil

At the top of the column it says to use katakana カタカナ

I guess that helps the staff for international names.

Brian said,

January 3, 2021 @ 6:18 pm

Regarding the use of katakana rather than hiragana, that is fairly standard on things such as wait lists for restaurants. Likewise, on any official documentation or forms in which you need to write your name in furigana above the kanji form, you will be instructed to write the furigana in katakana as often as in hiragana (in fact thinking about it now, I would say things like bank forms or governmental forms more frequently request katakana than hiragana). This is of course different to furigana in a book or magazine in which furigana is almost always in hiragana for native Japanese words.

Krogerfoot said,

January 3, 2021 @ 9:05 pm

Seconding david and Brian, this is a completely standard practice in Japan, so people might write their names on the list in katakana even if not explicitly instructed to do so at the top of the column.

What amuses me is that I've internalized the modern Japanese taboo about revealing "personal information." In a lot of contexts, taking a photograph of any document with other people's information on it is treated like an outrageous invasion of privacy and might result in a scolding from shop staff or other customers, as though a photo of a scrawled ヤマダ on a restaurant waiting list could lead to the Yamada family having their identities stolen and being jailed for crimes committed in their names. I think this taboo is well-meaning but silly, but I still jumped a bit when I saw the picture at the top of the post.

Twill said,

January 4, 2021 @ 12:43 am

I have always found placenames to be the most treacherous part of the Japanese writing systems, but that might have more to do with the subject matter than the difficulty of readings per se. Either way, needing several different voluminous dictionaries simply to be able to read words that appear in everyday contexts is an absurd state of affairs. The katakana is indeed explicitly solicited so is not necessarily representative of how people would write their names in similar contexts unprompted, but there's certainly nothing unusual about it.

Katakana has a much wider range of uses outside of foreign words, even if the first and most obvious use is loanwords full of sokuons and chuuons: onomatopoeia, vocables, animal and plant names, some given names, simply for effect, etc. etc.

Andreas Johansson said,

January 4, 2021 @ 2:22 am

Do people have official kana versions of their names, or are they essentially noting down pronunciation guides?

Krogerfoot said,

January 4, 2021 @ 8:23 pm

There's not much variation in which kana to use to represent Japanese words, including names. People who came of age in the last 25 years or so probably think of it in terms of computer entry; e.g., the sequence of keystrokes needed to get 鈴木 is s-u-z-u-k-i すずき + enter. I've never heard of anyone who decided to stylize their name as the homophonous s-u-d-u-k-i すづき, but if they did that they'd end up having to reprogram their devices to generate the correct kanji for that. So, in a sense people are writing the "official" kana version of their names.

People learn to write their names in kana before they learn kanji in school, so they wouldn't imagine it as being a pronunciation guide or some kind of stand-in for their name. It's just their name.

Andreas Johansson said,

January 5, 2021 @ 12:51 am

@Krogerfoot: Thank you.

Renzo Alves said,

January 5, 2021 @ 1:07 am

As above, if staff are going to call people by name they need to know how to say the name. Kanji have multiple pronunciations and people aren't limited to recommended kanji pronunciations. Therefore kana. Why katakana rather than hiragana? My guess, katakana less marked for biological gender, hiragana more associated with maruteki (or mangateki) young female uses, and of course as furigana.

Joseph said,

January 5, 2021 @ 5:25 am

I checked on chiebukuro.

Replies said katakana are easy to read and write. Often hiragana can be written in such a way that they can easily be mistaken. Also foreign waitstaff may appreciate the simplest way.

B.Ma said,

January 7, 2021 @ 3:52 pm

@Andreas Johansson

Wouldn't you consider Andreas and ANDREAS to both be a representation of your name? My surname is 馬 but it is also Ma. Depending on your relationship to me, I may or may not be offended if you call me Mr. Horse.

Andreas Johansson said,

January 9, 2021 @ 2:32 pm

@B.Ma:

Andreas and ANDREAS would both be official, in the sense I meant, versions of my family name.

But un-DRAY-us is not, for all that I might use it if I need to tell an anglophone the approximate pronunciation in writing.