The etiology of a self-inflicted earworm

I am prone / prey to earworms. Sometimes when I'm seriously affected / infected by one, it takes me weeks to get rid of the scourge, and I have to resort to all sorts of devices and deceptions to disinfect them from the space between my ears and the auditory cortex inside the lateral sulcus of the temporal lobe). (N.B.: I realize that there is at least one person on this list who detests slashes, but I find them useful for conveying a range of related meanings, among many other applications).

Unfortunately, in certain cases all it takes is to hear the name of or a line from an infectious song to trigger the ear worm, e.g., "Karma Chameleon" by Culture Club (for about the first hundred times I heard this song, I thought Boy George was saying "cama-cama-cama chameleon" and I had no idea what it meant [I thought it was just ladi-ladi-ladi-da sounds like Janis Joplin in "Me and Bobby McGee"] (uh-oh, just entered a danger zone by saying that). And now practically every time I turn on the radio, I hear Taylor Swift's "Karma", so I quickly get into double earworm territory.

Read the rest of this entry »

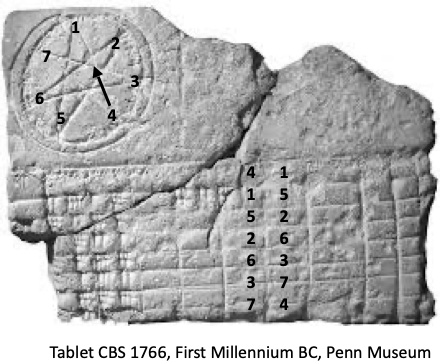

Calendars, old and new, are based on astronomical cycles: the yearly cycle of the sun; the monthly cycle of the moon. But there is one unit of time that doesn’t adhere to any celestial rhythm: the seven-day week.

Calendars, old and new, are based on astronomical cycles: the yearly cycle of the sun; the monthly cycle of the moon. But there is one unit of time that doesn’t adhere to any celestial rhythm: the seven-day week.