Archive for Writing

How to learn Chinese and Japanese

Some years ago (in 2008, as a matter of fact), I wrote a post entitled "How to learn to read Chinese". The current post is intended as a followup and supplement to that post.

Read the rest of this entry »

More on Bokmål

[During the last week or so of December, we had a vigorous, extended discussion on "Cantonese as Mother Tongue, with a note on Norwegian Bokmål". The following is a guest post by Håvard Hjulstad that takes up many of the issues that were raised in that earlier post and and attempts to situate them in a more systematic and comprehensive framework.]

It isn’t simple to explain the Norwegian language situation in a few words, but I shall try.

The word “mål” means “tongue” (or “language”; it also means “voice”) in the case of “bokmål”. It is very close to synonymous with “språk”, and it is used both for spoken and written languages. The word “mål” = “goal” and “measure” is a homograph. So “bokmål” could be translated as “book language”.

Read the rest of this entry »

Cantonese as Mother Tongue, with a note on Norwegian Bokmål

I just received this note from a colleague:

I found a document on the Hong Kong Education Bureau's website that says: "Xiānggǎng de qíngkuàng shì yǐ Zhōngwén wéi mǔyǔ 香港的情況是以中文為母語" ("The situation in Hong Kong takes Chinese as the Mother Tongue").

Zhōngwén 中文 ("Chinese") is a rather curious, ambiguous, and imprecise term since it can essentially mean just about any kind of Chinese. I think using it to refer to a person's so-called mother tongue is especially dubious and sneaky.

Read the rest of this entry »

Sneeze, hiccup, cough

Exceedingly few people (almost none) can write the Chinese characters for the Mandarin word for "sneeze" (dǎ pēntì). I suspect that most people would also get one or both of the characters for "cough" (késou) wrong, though it's not as hard as dǎ pēntì.

I mentioned this surmise to several colleagues and encouraged them to test themselves, their friends, and their students to see whether they could write késou correctly, or even at all. I cautioned them that it should not be permitted to use any electronic device or reference material (dictionaries, etc.) to remind those being tested how to write the two characters for késou. They must simply be written out directly on paper by hand.

Read the rest of this entry »

Manchu loans in northeast Mandarin

Wei Shao, who hails from Liaoning Province in northeast China (formerly called Manchuria), rattled off the following sentence in her local language and asked me if I understood it:

Wǒ dǎ cīliū huá'r de shíhou bǎ bōlénggài'r kǎ tūlu pí'r le.

I could only sort of understand the following parts: Wǒ dǎ … huá'r de shíhou bǎ …'r kǎ (?) … pí'r le ("When I was … slipping [?], I scraped [?] … the skin of…"). But it was all so fragmentary — mainly just the rough grammatical structure and three or four disconnected content words — that I really didn't know what was going on. Wei said not to worry, since no one from outside the area where she lives could understand it either.

Read the rest of this entry »

Poetry as "Word Temple" — NOT

Andrew Shields encountered the idea — on Facebook and vigorously promoted on this blog — that the Chinese character for poetry, shī 诗, consists of two parts meaning "word" and "temple". Furthermore, it is claimed that this is a particularly apt way to represent the notion of poetry, one that is conspicuously missing in Western culture.

Such a facile interpretation commits several fallacies, the chief of which is to misunderstand the history and nature of the character in question. After a careful examination of the evidence, it seems far more likely that shī 诗 has to do with the ritual performance of the odes by eunuchs, i.e., by reciters or singers who were castrati, than that it means "word" + "temple".

Read the rest of this entry »

Signifying the Local

I just found out about this new book on local languages in China. Judging from the abstract and table of contents, it looks very interesting and promising: Signifying the Local: Media Productions Rendered in Local Languages in Mainland China in the New Millennium. The publisher's blurb:

In Signifying the Local, Jin Liu examines contemporary cultural productions rendered in local languages and dialects (fangyan) in the fields of television, cinema, music, and literature in Mainland China. This ground-breaking interdisciplinary research provides an account of the ways in which local-language media have become a platform for the articulation of multivocal, complex, and marginal identities in post-socialist China. Viewed from the uniquely revealing perspective of local languages, the mediascape of China is no longer reducible to a unified, homogeneous, and coherent national culture, and thus renders any monolithic account of the Chinese language, Chineseness, and China impossible.

Read the rest of this entry »

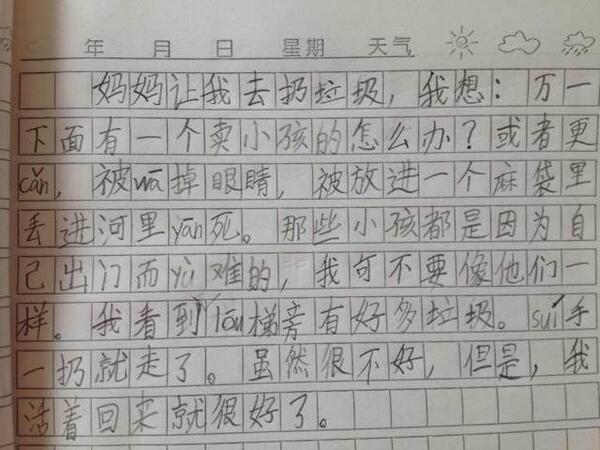

Sayable but not writable

The distinguished Chinese linguist, Y. R. Chao, developed the concept of "sayable Chinese" and wrote a series of books illustrating what he meant by it. Basically, what Chao intended by "sayable Chinese" were texts that could be understood when read aloud. This may sound like a somewhat ludicrous proposition for most languages where what is written on the page may be easily understood when read aloud slowly and clearly. For Chinese, this is not the case, especially when texts are riddled with Classical terms, sentences, and whole passages that are divorced from spoken language. But even parts of supposedly pure Mandarin texts may not be intelligible to someone who hears them read aloud, since the semantic carrying capacity of the morphosyllabic characters is greater than their sounds alone. That is why, when people tell others their names or when someone is giving a lecture or reading a text, auditors will frequently ask the speaker to write down the intended characters for terms that cannot be understood merely by hearing. Thus, there are many instances where things are writable in Chinese but not sayable.

Read the rest of this entry »

Stupid FBI threat scam email

I recently heard of another friend-of-a-friend case in which people were taken in by one of the false email help-I'm-stranded scams, and actually sent money overseas in what they thought was a rescue for a relative who had been mugged in Spain. People really do respond to these scam emails, and they lose money, bigtime. Today I received the first Nigerian spam I have seen in which I am (purportedly) threatened by the FBI and Patriot Act government if I don't get in touch and hand over personal details that will permit the FBI to release my $3,500,000.

I wish there was more that people with basic common sense could do to spread the word about scamming detection to those who are somewhat lacking in it. The best I have been able to do is to write occasional Language Log posts pointing out the almost unbelievable degree of grammatical and orthographic incompetence in most scam emails. Sure, everyone makes the odd spelling mistake (childrens' for children's and the like), but it is simply astonishing that literate people do not notice the implausibility of customs officials or bank officers or police employees being as inarticulate as the typical scam email.

The one I just received is almost beyond belief (though see my afterthought at the end of this post). The worst thing I can think of to do to the senders is to publish the message here on Language Log, to warn the unwary, and perhaps permit those who are interested to track the culprit down. I reproduce the full content of the message source below, with nothing expurgated except for the x-ing out of my email address and local server names. I mark in red font the major errors in grammar and punctuation, plus a few nonlinguistic suspicious features.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off

Of toads, modernization, and simplified characters

Considering the fact that we've had a lot of traffic on spelling bees, character amnesia, simplified characters, and whatnot on Language Log recently, it's not surprising that the following article by Dan Kedmey would appear in Time yesterday (Aug. 15, 2013), though without any mention of Language Log: "What the Word 'Toad' Can Tell You About China’s Modernization".

At first I was going to just write a short note about this article and add it as a comment to this post from a week ago. But the more I read through the article, the more annoyed I became by how riddled with errors it is. So I've decided to write this post listing some of the more egregious mistakes, lest innocent readers be led astray. After all, Time still commands a substantial readership, so the magazine needs to be held accountable for the accuracy of its statements, even when writing about something so supposedly quaint as Chinese — which, by now, certainly should no longer be viewed as exotic at all, since China has become very much a part of the global economy.

Read the rest of this entry »

More on Juola's stylometry

Worth reading if you were interested in the computational stylometric analysis by Patrick Juola that helped to unmask J. K. Rowling as the author of The Cuckoo's Calling: an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education about Juola's work.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink Comments off