Archive for Multilingualism

Multilingual Utica confronts COVID-19

From Brenton Recht:

I live in a city with a large immigrant population in general and a large Bosnian population in particular (Utica, NY [VHM: population around 60,000; between Syracuse and Schenectady]). As such, I see "BiH" bumper stickers once in a while on the road. Most of the Bosnian population either came during the breakup of Yugoslavia or are children of those immigrants, so they are probably following the American trend of putting round stickers on your car for things you like or identify with, rather than the European usage of using them to identify country of origin.

Read the rest of this entry »

Cantonese: good news and bad news

The good news is that it's a language.

The bad news is that you can't speak it.

"China’s version of TikTok suspends users for speaking Cantonese: ByteDance’s short video app Douyin has been urging live streamers to switch to the country’s official language", Abacus via SCMP (4/3/20)

I've been hearing similar reports concerning the use of Cantonese on other social media: it is definitely discouraged or even forbidden. At least, though, the Abacus article does not miscall Cantonese a dialect, but affords it the dignity of referring to it as a language.

Read the rest of this entry »

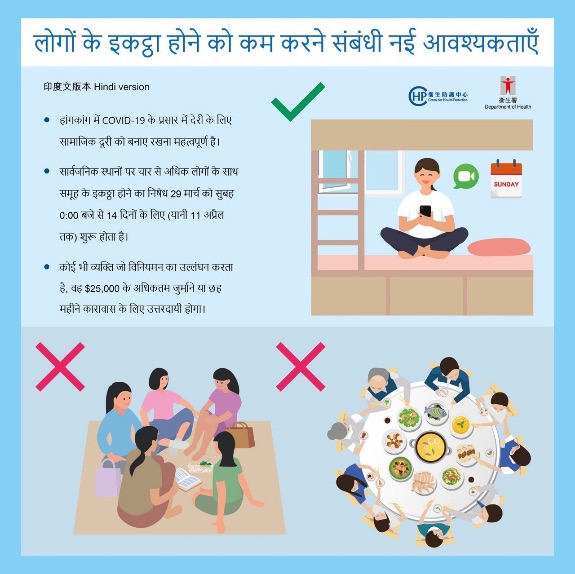

Social distance posters in various Asian scripts

At first I thought these might have come from Singapore or some other Southeast Asian country, but upon closer inspection, I see that they are from the Hong Kong Department of Health, which was confirmed by Fraser Howie, who sent them to me. They are respectively in Hindi, Indonesian, Thai, Nepali, Bengali, Sinhala, Urdu, Vietnamese, and Tagalog. Upon further reflection, it is clear that the content of the posters is directed at the foreign domestic helpers who comprise five percent of Hong Kong's population. One of their favorite activities when they have time off from their jobs is to gather in groups in public places, sitting on the ground or on benches to chat and often to enjoy what to me seems like a picnic.

Read the rest of this entry »

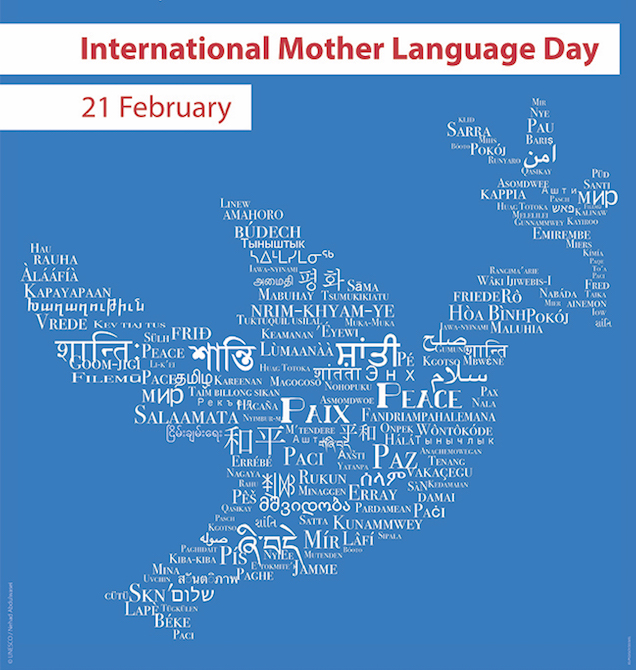

Preventive Care for Local Languages

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

We’re told “Don’t wait” to treat our bodies, secure our homes, or maintain our cars. We should do the same for local languages.

Despite all the years of language revitalization, we are still losing about one language every two to three weeks. In this century alone, the number of languages on the planet will be halved. A little preventive care would help.

Read the rest of this entry »

A Sino-Mongolian tale in three languages and five scripts

"Silk Road Tales: A Look at a Mongolian-Chinese Storybook"

By Bruce Humes, published

"Add oil," Kongish!

Speakers of Kongish have three ways to write their equivalent of English "Go!": 1. "ga yao" (Cantonese Romanization of the wildly popular term), 2. 加油 (the Sinographic form of the Cantonese expression), 3. "add oil" (Chinglishy equivalent of the former two forms).

See this excellent article by Lisa Lim for a brief introduction to Kongish:

"Do you speak Kongish? Hong Kong protesters harness unique language code to empower and communicate: The mixed code of romanised Cantonese and English has helped popularise phrases such as ‘add oil’, from Cantonese ‘ga yau’", SCMP (30 Aug, 2019). [VHM: Includes a nice summary of Romanization efforts for Sinitic topolects from the late 16th century (Matteo Ricci) to the present.]

Illustration from the article:

Read the rest of this entry »

Green box deep male shrine

Photograph taken by Yuanfei Wang in Baihou Town 百侯镇, Tai Po 大埔, Guangdong Province:

Read the rest of this entry »

Can a person have more than one native language?, part 2

Based on these two tweets, this 85-year-old Swedish woman has at least two native tongues:

https://twitter.com/yanxiang1967/status/1122325028396126209

Read the rest of this entry »

Can a person have more than one native language?

The following paragraph began as a comment to this post: "How to maintain first and second language skills" (4/25/19)

How can a person acquire not just one, but two or more native languages? Now in China, some parents aspire to help their children learn both Chinese and English as their native languages. But, considering the drastic differences between the two languages, it seems to be quite a difficult goal to achieve, to use both languages equally well. A very interesting case I met is a 6th grader from an international school, a Chinese boy who spoke fluent English but stammering Chinese. He had to stop to organize his Chinese when trying to express complicated ideas. His parents are both native Chinese, and they sent him to an international primary school. There are undoubtedly many other students like him, since China has so many international primary and secondary schools. Their parents must have taken great effort making English the first language of their children. But why? And in the almost monolingual Chinese environment, I wonder if English as their first language could be as equally efficient as that of a real native speaker.

Read the rest of this entry »

Mayor Pete's multilingualism

Sure, you may have heard that Pete Buttigieg, now on the presidential campaign trail, can speak a surprising number of languages. Now the Washington Post compiles the evidence in one video, under the appropriate headline, "Mayor Pete speaks a lot of languages, even when he's not fluent." In the video, Polyglot Pete shows off his varying skills in French, Arabic, Spanish, Italian, Farsi (aka Iranian Persian), Dari (aka Afghan Persian), and Norwegian. Oddly, there's no footage of him speaking Maltese, which is likely the foreign language in which he has the most fluency, given that his father is from Malta.

Read the rest of this entry »