Preventive Care for Local Languages

« previous post | next post »

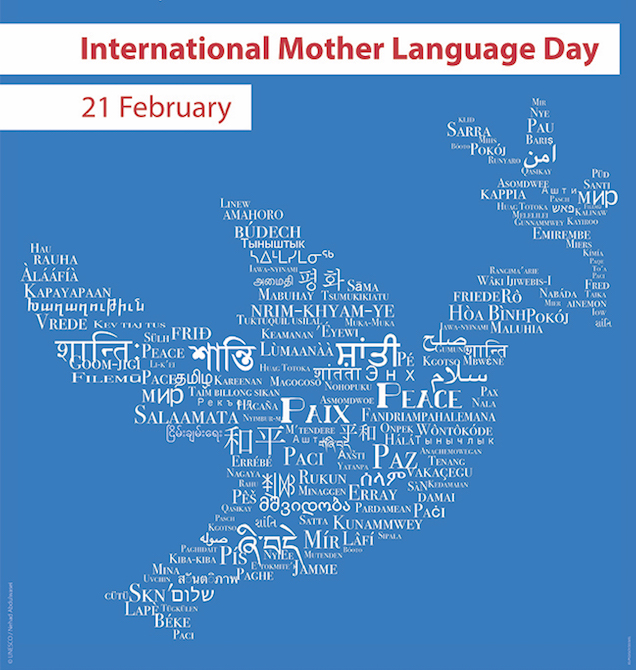

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

February 21st is International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1999 and celebrated every year since, aimed at promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism. In honor of the day, the following is a guest post by Alissa Stern, the founder of BASAbali, an initiative of “linguists, anthropologists, students, and laypeople, from within and outside of Bali, who are collaborating to keep Balinese strong and sustainable.” BASAbali won a 2019 UNESCO Award for Literacy and a 2018 International Linguapax Award.

We’re told “Don’t wait” to treat our bodies, secure our homes, or maintain our cars. We should do the same for local languages.

Despite all the years of language revitalization, we are still losing about one language every two to three weeks. In this century alone, the number of languages on the planet will be halved. A little preventive care would help.

There are many reasons to keep local languages strong. Local languages provide windows into different ways of thinking. UNESCO identifies local languages as an integral part of human rights. Local languages hold deep cultural knowledge, provide a bridge to traditions, and allow community to identify and value itself in the modern world. They are the soul of a people.

We need early-proactive engagement — from the local community and from the rest of the world –to prevent a local language from reaching the brink of extinction. And not just to keep the language alive in a narrow sense, but the larger ecosystem in which it operates – the way we need to change not just vitamins to improve our overall health, but also our lifestyle, diet, and exercise.

At BASAbali, a collaboration of scholars, artists and advocates fueled by passionate millennials, we’re trying to change public behavior and attitudes toward local languages. We’re focusing on Balinese, one of Indonesia’s 700 local languages that still has a strong base, but like the vast majority of local languages, is threatened (note that a study by Ravindranath and Cohn showed how even a language like Javanese, with over 80 million speakers, can be at risk. Balinese has something closer to 1-3 million speakers, measurement being another difficult issue).

We engage the public in strengthening the local language and culture through a multimedia, multilingual wiki dictionary and virtual library which invites the public to help shape the platform and add original local language content while also trying to inspire people to use Balinese in other ways, in more places, more of the time.

We think that even getting tens of thousands of people to participate in a language revitalization program isn’t enough to sustain a language into future generations. So although close to 1 million people have used the wiki, contributing 16,000 words to the dictionary side of the wiki and over 4000 videos of people using those words in context, what we’re really concerned about is how people are using, valuing, and encouraging others to use the language, not how many people are using, adding to or even shaping the platform.

To that end, we’re really excited that the wiki inspired the public to create an artists’ directory, a people’s history, a virtual meeting place for environmental groups to share resources, local language crossword puzzles, and most recently, a multilingual environmental teen superhero who speaks with the public via her own social media handles. The superhero’s adventures were just used by a program sponsored by the US State Department to teach creative writing to Balinese teachers using local language materials. We’ve also seen a visible increase in the number of people posting and texting in Balinese, there are now websites and social media groups in Balinese, memes in Balinese abound, the Governor of Bali has declared that once a week, Balinese will be used in schools and offices, and young people are making waves by writing essays, short stories and novels in modern Balinese, together creating something of a public movement to keep Balinese strong.

From the wiki experience, we’ve learned that to sustain languages, we need to think holistically by also promoting a joy of reading (as a separate matter from literacy) and by encouraging young people to text, post, sing, and take pride in local languages among themselves and as a behavioral model for their younger peers. We learned that we need to teach basic internet skills to those who aren’t yet digitally literate so that they can participate in online initiatives, that we have to be open to thinking in cyclical, oral, stratified, performative ways of other cultures, and that we need to raise up the value of local languages in the eyes of the international community in addition to focusing on changing behavior and attitudes locally.

February hosts International Mother Language Day and in the same month, two more languages will disappear from the planet. It's time we treat languages and their ecosystems with preventative medicine and give them a fighting chance to survive.

Michael M said,

February 21, 2020 @ 1:49 am

I know international typography is difficult, but when language organisations make those kinds of mistakes it's really offputting. The Thai still has the unicode placeholder circles, and sāma and paċi have lowercase in a different font because they didn't have the small-caps characters for those. And is sāma supposed to be Pali in Latin script? They clearly just took all the words from this page (http://www.columbia.edu/~fdc/pace/) and did no double checking. Points for getting a Yi font, I guess?

Philip Taylor said,

February 21, 2020 @ 6:36 am

I am intrigued to know why Luh Ayu Manik Mas is a "superhero" and not a "superheroine". Has the latter now joined the list of "no longer felt to be relevant / appropriate / whatever" terms such as "actress", "waitress" and so on ? Or is it simply an error in translation ? The Japanese certainly seem to have no problem with the term "superheroine", given the number of video titles in which the word appears [1].

[1] Hyperlink added and then removed, since all returned hits were to sites of "dubious moral value".

David Morris said,

February 21, 2020 @ 7:14 am

My eye was caught by 'Fred' on the stalk just above the bird's beak. The internet quickly told me that it's Danish/Norwegian/Swedish, with cognates in Germanic languages, eg Friede, Frieden in German.

Say PEACE in all languages (http://www.columbia.edu/~fdc/pace/) might be of interest. They state they've listed 314 languages. That's not *all*.

Phillip Helbig said,

February 21, 2020 @ 8:45 am

Is is still true (or was it ever) that most languages are in New Guinea?

J.W. Brewer said,

February 21, 2020 @ 9:46 am

Showing diversity by hundreds of different versions of a single "word" is an unfortunate example of the "language as a bag of words" misconception. Having a few hundred versions of the same phrase or sentence is better, because it will show the considerable range of morphosyntactic variation. Sometimes one sees pious compilations of hundreds of different versions of the Lord's Prayer or parts thereof, but instead of merely "peace" maybe they could do hundreds of different versions of the second half of Matthew 10:34 ("I came not to send peace, but a sword.")? (This would of course need to bracket the issue that many languages have multiple Bible translations that tend to demonstrate that there can be quite a large number of sentences in any given target language that are defensible versions of the Greek original.) In Balinese it's apparently "Tekan Gurune dongja ngaba dame, nanging ngaba cerah."

Alissa Stern said,

February 21, 2020 @ 11:26 am

Thank you for raising this issue, Philip.

We have native english speakers translating from Balinese into currently accepted English, which presents challenges since our translators are from Australia, the UK and the US. But all felt that most native English speaking teens use the word "superheroine" to refer to a drug not a hero. :)

Philip Taylor said,

February 21, 2020 @ 11:52 am

Or perhaps even of Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος — a very devout Greek Orthodox friend assures me that there is far far more to λόγος than is, or can be, ever captured in our simple word "word".

Scott P. said,

February 21, 2020 @ 12:36 pm

Has anyone attempted to produce an estimate for the number of languages created per century, or whatever interval? Obviously new ones appear, or we'd all be speaking Nostratic.

Philip Taylor said,

February 21, 2020 @ 1:05 pm

I don't know the answer to your question, Scott, nor do I know when the most recent (natural) language was created. But creation of itself is less important, it seems to me, than whether or not (a) the language gains reasonably widespread adoption, and (b) does not disappear again within a relatively short space of time. My guess is that fewer than one language (meeting both of these criteria) is created per century.

Chester Draws said,

February 21, 2020 @ 2:49 pm

Local languages provide windows into different ways of thinking. [citation required]

This is basically Sapir-Wharf, and I'm not having a bar of it.

Small local languages prevent communication between people, and that is not a good thing. That's why they are dying — because they don't give people what they need, which is access to the modern world. If you live in a big city, then speaking the tongue of your local valley just is an impediment — no-one else does, so who would you talk to? Whereas learning a language like English, Tagalog, Hindi etc gives you access to a much greater world.

If small local languages are to be kept, then we need to prevent their speakers from moving to places they would prefer to be, and keep them from using much more powerful languages that allow them to communicate with more people. It's basically putting them in a museum because someone else wants them to keep something. Hell, why not keep them in grass skirts and without sanitation while we are at it!

Losing those languages is a shame, but it is better than the alternatives.

Chester Draws said,

February 21, 2020 @ 2:50 pm

Sapir-Whorf. I hate autocorrect.

Scott P. said,

February 21, 2020 @ 3:49 pm

Philip,

It's interesting, because a) they have apparently tried to calculate the rate languages are disappearing, but I have never heard of the reverse, which ought to also be interesting, and b) if we have a rate of appearance and a rate of disappearance, we can model how many languages will be around, say 100 years from now. I agree that one would want to model number of speakers, since for one the 'death rate' would presumably relate to the number of present speakers in inverse proportion.

… Though does that also occur as new languages emerge? We conceive of languages dying out bit by bit until there is a smaller and smaller population, and then the last native speaker dies. But presumably languages aren't born the same way. How much research has been done on this? Is there a good analogy with the emergence and extinction of biological species.

Philip Taylor said,

February 21, 2020 @ 5:03 pm

For a language to be created (other than by an individual or committee for essentially academic reasons), there would have to be enormous motivation, since there is probably not a person alive who was born and raised in a place where language does not exist. And once a person has a language, there is little incentive to create another, unless there is a very good reason for doing so — for example, a desire to keep one's thoughts secret (not necessarily secret to oneself, but secret from a group). Indeed, I read not long ago (unfortunately I forget both where I read it and about where it concerned) that a prison population had deliberately created a secret language, and that new inmates were virtually forced to learn it if they wished to avoid very serious trouble. History tells us of the emergence of Cockney rhyming slang, Romanies have their own secret language and so on, but I do not recall reading of any language being created solely for the purposes of normal communication as opposed to communication with secrecy. Languages evolve, obviously, but that is very different to being created,

Doug said,

February 21, 2020 @ 5:25 pm

Scott P. wrote:

" if we have a rate of appearance and a rate of disappearance, we can model how many languages will be around, say 100 years from now."

I would say that to model that, all we need is (an estimate of) the rate of disappearance. The annual rate of language creation/emergence is clearly small in comparison — surely smaller than the uncertainty in any estimate of language loss.

So, for purposes of predicting the future language count, the rate of language creation is zero, within rounding.

Philip Anderson said,

February 21, 2020 @ 5:36 pm

I have never seen ‘superheroine’. Nowadays, my experience is that gendered terms like ‘actress’ and ‘heroine’ are only used when gender is significant, e.g. when talking about a female actor playing a female character, or the main female character in a novel, who probably marries the (not necessarily heroic) hero.

But for the occupation, ‘actor’, ‘hero’ or ‘superhero’. In the past there were actresses and (pagan) priestesses, but I don’t think even the most conservative speakers call today’s women priests ‘priestesses’. If an older active mind can still learn new words, I don’t see why it can’t learn new usages and idioms.

Philip Anderson said,

February 21, 2020 @ 5:44 pm

Regarding language creation, while languages are occasionally invented (e.g. Esperanto), most languages are created by divergence (all the Romance languages from Latin). Multiple Englishes are diverging nowadays, although not (yet) different languages. How many Arabic languages are there?

Doug said,

February 21, 2020 @ 6:05 pm

I think "heroine" has been on the way out for a long time, partly because it sounds like "heroin," and partly because it wan;t really semantically parallel to "hero" in the first place. The "heroine" of a book or movie is often not a woman who does heroic things, but a woman romantically linked to or rescued by the hero.

I presume you've encountered the coined word "she-ro" to mean female hero.

The fact that someone felt compelled to coin that seems like a clear indication that "heroine" didn't seem to convey the right idea.

Philip Taylor said,

February 21, 2020 @ 6:43 pm

Well, I confess I have never previously heard of a "she-ro" (with or without hyphen). However, the Google n-grams viewer shews "superheroine" emerging in 1944, and after a somewhat shaky start, rising steadily from 1986 onwards.

Ben Zimmer said,

February 21, 2020 @ 6:50 pm

Here's a Wall Street Journal column I wrote about "shero" in 2017 (link).

With the Help of Barbie, the Term ‘Shero’ Gets New Fans

From an 1851 humor piece to marketing by Mattel

By Ben Zimmer

Nov. 24, 2017 10:12 am ET

Mattel recently unveiled the first Barbie doll to wear a hijab, modeled on U.S. Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad. It’s the latest in a series of Barbie dolls dubbed “Sheroes”—“female heroes who inspire girls by breaking boundaries and expanding possibilities for women everywhere,” in Mattel’s words. Other dolls in the “Sheroes” line are modeled on gymnast Gabby Douglas, director Ava DuVernay and ballet dancer Misty Copeland.

The word “shero,” blending “she” and “hero,” has been circulating since the 19th century to refer to women worthy of admiration. Early on, however, it was mostly used as a jokey name for a female companion of a male hero.

In a bit of dialect humor that appeared in the newspaper Spirit of the Times in 1851, a writer identified as “Curnill Jinks” tells of the founding of Satartia, a town in Yazoo County, Miss., by “the illustrious hero an [sic] the shero, his wife.” An 1880 item in the National Police Gazette was titled, “A Love Drama in One Act: In Which the Hero, Shero, Two Small Boys, and a Dozen of Hen Fruit Play Leading Roles.” And in an 1897 essay, Ambrose Bierce imagines a novel where “my assistant hero learns that the hero-in-chief has supplanted him in the affections of the shero.”

The women’s liberation movement of the 1970s put a more empowering spin on the word, at a time when feminists were taking a critical look at language, transforming “history,” for instance, into “herstory.” Two prominent African-American women were the first to embrace “shero” as a term of pride. The poet and author Maya Angelou spoke of “heroes and sheroes” in a 1977 lecture. And Johnnetta B. Cole, an anthropologist who would go on to serve as president of Spelman College, helped propel the word with her saying, “For every hero in this world, there’s at least one shero.”

Both Ms. Angelou and Ms. Cole served as inspirations for Varla Ventura when she wrote her book, “Sheroes: Bold, Brash, and Absolutely Unabashed Superwomen from Susan B. Anthony to Xena,” published in 1998. At the time, she noted, “television’s supreme shero,” Oprah Winfrey, had “adopted the word into her public vocabulary.”

But Ms. Ventura wanted to go further, writing, “Let’s get ‘shero’ into Webster’s Dictionary, Scrabble, the collective consciousness, and, most importantly, the common parlance!” She even included a form letter in the back of the book that readers could fill out, addressed to Merriam-Webster. A press release for her letter-writing campaign argued that “the word ‘hero’ reeks of masculine overtones while the feminine form—‘heroine’—sounds like the name of a narcotic drug.”

Merriam-Webster sent replies to those who wrote in, explaining that “at this point, the evidence we’ve accumulated for ‘shero’ is not enough to justify its inclusion” in the company’s Collegiate dictionary. But that evidence eventually won out, and the word was added to the Collegiate in 2008, 10 years after Ms. Ventura launched her campaign. And now “shero” has achieved the ultimate online success: becoming a popular Twitter hashtag.

James Parkin said,

February 21, 2020 @ 7:09 pm

@Chester Draws "Kill the Indian, save the Man."

Peter Grubtal said,

February 22, 2020 @ 2:08 am

Chester Draws had the moral courage to make a point which is bound to attract cheap shots, as from Mr. Parkin.

The problem came to my attention recently with a report on a UNICEF programme in Peru to make school material available in local indigenous languages for kids, who partly because of the remoteness of where they live, and partly because they only speak, for example, Quechua, are missing out on serious education.

It all seemed very praiseworthy, but towards the end of the report it became clear that to give every kid the same chance they'd have to provide the material not just in Quechua but also in several other indigenous languages used in Peru. And I can imagine that in a country with the size and geography of Peru, Quechua exists in several strongly differing dialects.

To get on in higher education and participate on equal terms in Peruvian society, these children are in the end going to have to learn Spanish, and if they move on to University education, probably English as well.

Perhaps for primary level education, the programme (if they can get sufficient resources to do it properly) might be a good thing for these kids, but moving on beyond that level, as Chester Draws points out, are you doing them a favour if they don't become fully competent in Spanish?

The disappearance of languages is regrettable but it seems inevitable.

Alissa said,

February 22, 2020 @ 9:20 am

We are strong believers in multilingualism

That is why the wiki dictionary and virtual library — and all the superhero books — are in the local language (Balinese), national language (Indonesian) and an international language (English).

We think that local languages can be relevant and valuable in the modern age and that we also need to be fully competent in national and international languages to communicate with and access information from the rest of the world.

James Parkin said,

February 22, 2020 @ 11:37 am

Firstly, I'd say the real cheap shot is blithely dressing up old arguments for genocide in new clothing, because (1) Nobody said that efforts to sustain and promote heritage languages must exclude learning dominant languages as well (being that multilingualism has been a human norm for thousands of years), and (2) People who surrender their heritage languages/cultures may well join the wider society, only to discover they remain 2nd class citizens, subject to pervasive discrimination and violence at the hand of state agents while also facing the trauma of culture loss, and (3) Research and anecdote both support the idea that retention of language/culture is strongly associated with good outcomes, educationally and economically, and (4) My own experience working in Native American language revitalization has shown me beyond doubt that a fostering a strong cultural identity and good knowledge of ones heritage language brings nothing but good to those who involved.

Ellen K. said,

February 22, 2020 @ 11:38 am

@Chester Draws

Speaking a small local language only impedes participation in the larger world if it is instead of knowing a national or world language (or other lingua franca), rather than in addition.

I do think it's certainly wrong for English speakers/writers to be wanting the preservation of languages with few speakers without combining that with support for multi-lingualism. No, we have no right to tell others they shouldn't speak a world language. That pretty much would be people in a place of power saying others can't join them. But supporting preservation of such languages along with speaking another language, that's a good thing, as long as it's supporting the speakers of those languages, and giving them power and space to be themselves, rather than trying to control them.

cliff arroyo said,

February 22, 2020 @ 11:59 am

"instead of knowing a national or world language (or other lingua franca), rather than in addition"

I'm not sure about Chester or Peter's background but there is a persistent idea of language knowledge as a zero sum game in the English speaking countries. That is the idea seems to be that knowledge of one language precludes knowledge of another – with monolingualism in the language of highest prestige as the most appropriate goal for minority communities.

It's kind of nonsense. Learning enough English, Russian or Spanish or Chinese to participate in the local mainstream does not require giving up other languages.

At the same time it's not super easy to create or maintain bilingual societies. Surely the best people to decide on the relative costs and benefits are the people who speak minority languages themselves, preferably with a broad idea of said costs and benefits and not just a few glib slogans repeated by well-meaning outsiders.

D.O. said,

February 22, 2020 @ 1:24 pm

With modern means of communication, communities of speakers can stay in touch and not split their language even when there is no face to face contacts. So it'shard to say what happens these days, but if we assume not unreasonable rate of language split as every 300 years then with 6000 languages it is 20 new languages a year. One every two-three weeks.

Doug said,

February 22, 2020 @ 2:36 pm

D.O.:

" if we assume not unreasonable rate of language split as every 300 years "

Hmm, assuming very conservatively that there was only one language 10,000 years ago, and it (and its descendants) split 2-for-1 every 300 years, there's been time for 33 splits, so we should have 2^33 languages. That's 8.6 billion languages. Either that's a large overestimate of the language split rate, or else there was a nearly offsetting rate of language death, even long before the European expansion and subsequent globalization.

Philip Taylor said,

February 22, 2020 @ 3:35 pm

If we assume that divergence ("splitting") rather than creation is the norm for languages, and has been for perhaps a few thousand years (is this a reasonable assumption), then what is the most recent split for which there is reliable evidence ?

D.O. said,

February 22, 2020 @ 3:52 pm

" or else there was a nearly offsetting rate of language death, even long before the European expansion and subsequent globalization."

Yes.

I am not sure about 10000 years figure, but anyway, unless there is a huge population explosion (as was in the last 200 years) or discovery of new large uninhibited (by humans) lands, the number of spoken languages should reach some form of steady state.

Doug said,

February 23, 2020 @ 9:01 am

Philip Taylor said:

". . . what is the most recent split for which there is reliable evidence ?"

I'm totally unqualified to address this question, but in spite of that:

It's likely that the rate of language split/emergence has been low in recent times, for the same reasons that the rate of language death has been high. If I told you that X became a new language this year, you'd naturally ask, "Then what was X last year, if not yet a new language?" The only sensible answer would be "it was a highly divergent dialect of Y, but not quite a distinct language on my estimation." And highly divergent dialects of large languages seem to be dying out just as minor languages are.

Haitian Creole, I'm told, emerged in the 18th century, and I gather that many other creole languages did as well. Afrikaans comes from the same time period.

Michif emerged in the 19th century.

Twentieth century candidates are harder to come by. I'm told that in light of political events on the Balkans, some linguists are more likely to speak of Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian languages rather than one Serbo-Croatian language, even though linguistically not much has changed.

Rose Eneri said,

February 23, 2020 @ 10:08 am

I'll repeat a story I've told many times.

My grandmother was 1st generation American whose parents were from Poland. The family lived in a Polish section of Philadelphia. My grandmother never heard English until her first day of school. She got an education and learned to speak perfect English without an accent and without any special training.

Her mother, my great-grandmother never learned English, my grandmother was fully bi-lingual and my father was totally mono-lingual in English. My husband's family was the same way. His grandparents spoke Yiddish, his parents were bi-lingual and he's mono-lingual. That's how immigrants to the US did it back then.

Not speaking the relevant lingue franca is a huge disadvantage, but learning it should not mean abandoning one's native language.

chris said,

February 24, 2020 @ 11:20 pm

Not speaking the relevant lingue franca is a huge disadvantage, but learning it should not mean abandoning one's native language.

Would you say that your father abandoned his native language? It doesn't seem that way to me. He just has a different native language than his mother and grandmother.

Hypothetically if your family were the last Poles on Earth, then the language would die with your grandmother, but your family would obviously go on, so I admit I have a hard time seeing the tragedy in that, and it's certainly not comparable to genocide.