Archive for Translation

September 19, 2025 @ 5:38 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Language and art, Language and religion, Translation

Sino-Platonic Papers is pleased to announce the publication of its three-hundred-and-sixty-eighth issue:

“Demetrios of Bactria as Deva Gobujo and Other Indo-Greek Myths of Japan,” by Lucas Christopoulos.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

September 17, 2025 @ 5:34 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Names, Politics of language, Translation

Mark Metcalf wrote:

Currently working my way through an excellent book on Jūnshì lúnlǐ wénhuà 军事伦理文化 (The culture of military ethics) and started noticing that the author ping-pongs between Zhōngguó 中国 and wǒguó 我国 when discussing various aspects of the PRC's history and alleged achievements. Are you aware of any general guidance regarding how the decision is made to use one term or the other? Topical? Polical? Tone? I'll keep digging and let you know if anything jumps out at me.

BTW, one UVA colleague described how he had to teach first year PRC students that "my country" was not an acceptable synonym for China when writing literature essays.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 25, 2025 @ 4:37 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Grammar, Translation

"Arabic Translations of the English Adjective 'Necessary': A Corpus-Driven Lexical Study." Alhedayani, Rukayah et al. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12, no. 1 (August 18, 2025): 1345.

Abstract

Modal adjectives of non-epistemic necessity are very common in language corpora. However, such adjectives are expected to behave differently in context, and thus differences between them should be highlighted in dictionaries. Nevertheless, there are a few studies that have examined modal adjectives with respect to their associated constructions and meanings in English. More importantly, studies on equivalent Arabic modal adjectives are scarce. Hence, the present study is quantitative and corpus-driven utilizing monolingual (i.e., the arTenTen18 and the enTenTen18) and parallel (i.e., Open Parallel Corpus or OPUS for short) corpora. Further, it is based on construction grammar and frame semantics to explore Arabic and English words of necessity.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 31, 2025 @ 5:06 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and travel, Signs, Translation

A sign just outside the driver's cab of a TRA (Taiwan Rail) aging diesel on the Pingxi Line that climbs along the edge of the Keelung River ravine, just outside Taipei.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 29, 2025 @ 6:31 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and food, Language and politics, Translation

On first blush, I thought perhaps the person pictured had a double chin, and by cropping the photo this way they were trying to hide it. On second blush, it was clear that they had misinterpreted the name of the famous 2nd c. statesman, general, and poet, Cao Cao 曹操 (ca. 155-220 AD).

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 13, 2025 @ 5:49 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Humor, Multilingualism, Pronunciation, Punctuation, Translation

A learned friend recently sent me a draft composition on medieval Chinese history in which he referred to "*" as an "asterix". This reminded me that ten years ago I wrote a post, "The many pronunciations of '*'" (12/17/15), on this subject and we had a lengthy, vigorous discussion about it.

Given that lately we've been talking a lot about Celts, Galatians, and so on, I think it is appropriate to write another post on Asterix the Gaul, that famous French comic book character, and how he got his name. Also inspired / prompted by Chris Button's latest comment.

I often hear "*" pronounced "asterix" or "asterick", and so on (e.g., "astrisk" [two syllables], esp. in rapid speech). It's hard even for me to pronounce "*" or type the symbol those ways, so ingrained is the pronunciation "as-ter-isk".

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 4, 2025 @ 8:00 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and literature, Multilingualism, Translation

What with all the talk about Taiwanese and Gaelic swirling around Language Log recently, I was serendipitously surprised to find this in my inbox last week:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 10, 2025 @ 7:47 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Grammar, Language and literature, Translation

Randy Alexander is not a professional Sinologist, but when it comes to reading Chinese poetry, he's as serious as one can be. The following poem is by Du Fu (712-770), said by some to be "China's greatest poet". In the presentation below, I will first give the text with its transcription, and then Randy's translation. After that we will delve deeply into the grammatical exegesis of one line of the poem, the last.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

May 21, 2025 @ 12:12 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and philosophy, Philosophy of Language, Translation

Blake Shedd called my attention to

…an article on philosophy / human rights and how a Chinese translation of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (available online from Philosophy Now, 118 [February-March, 2017], 9-11, and also available here from the website of one of the authors) raises some questions of hermeneutics.

Here's the article:

Hens, Ducks, & Human Rights in China: Vittorio Bufacchi & Xiao Ouyang discuss some philosophical & linguistic difficulties

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

May 7, 2025 @ 7:27 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and politics, Translation

From Mok Ling:

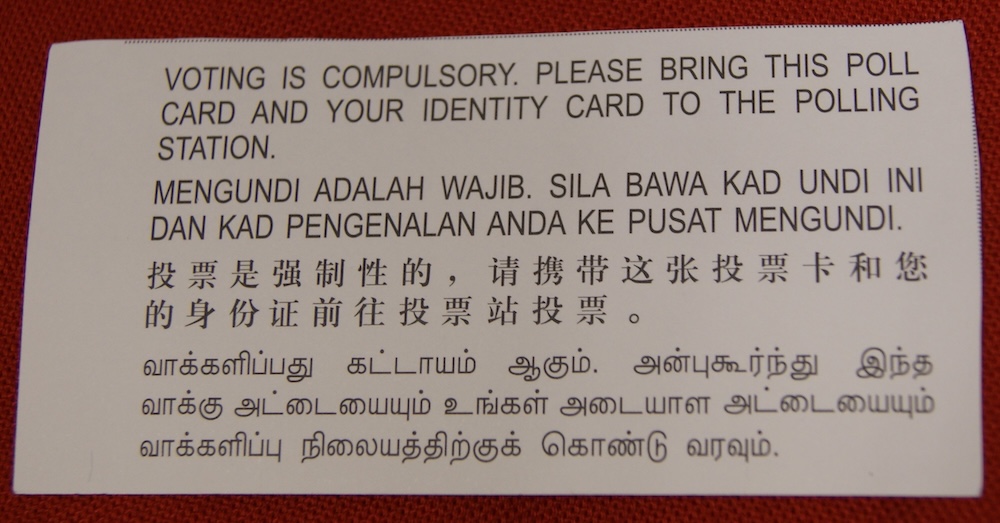

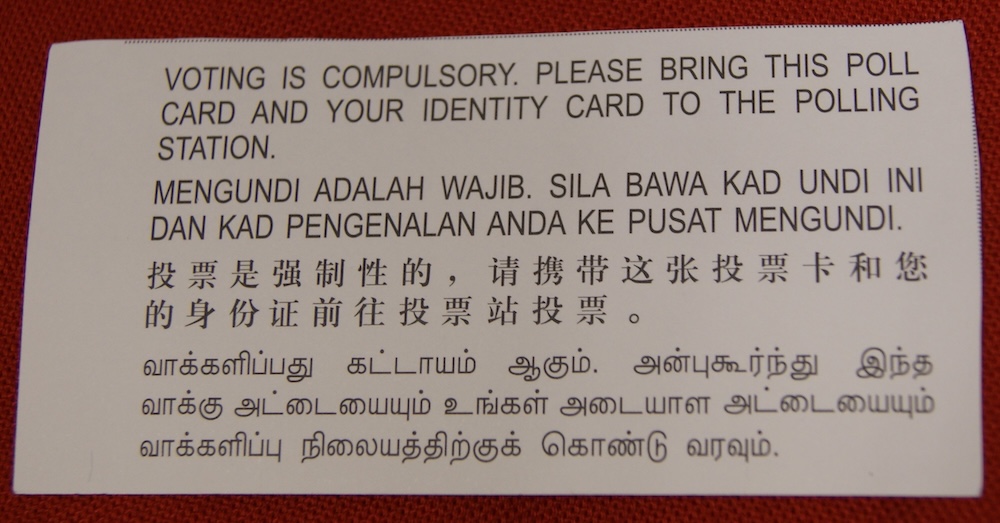

As I'm writing this (evening of 3 May), my friends across the Strait of Malacca in Singapore are eagerly awaiting the results of their most recent general elections. As I've found out, in Singapore, voting in elections is not only a civic duty but mandatory by law!

I happened to come across this image showing the reverse of a poll card issued to all voters:

The reverse of a poll card issued for the Singaporean presidential election, 2011.

The polling station in question was at the void deck of Block 115 Clementi Street 13

in the Holland-Bukit Timah Group Representation Constituency. (source)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 23, 2025 @ 6:52 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Announcements, Books, Language and literature, Translation

Two days ago, I received a big package with three heavy books inside. They were three copies of the following tome:

Routledge Handbook of Traditional Chinese Literature, ed. Victor H. Mair and Zhenjun Zhang (London: Routledge, 2025), 742 pages.

It came as a surprise for, even though we had been working on the handbook for years, I had lost track of when it would actually be published.

Holding the printed and bound work in my hands, the sheer magnitude of what its pages contained began to sink in.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 2, 2025 @ 7:34 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Language and culture, Transcription, Translation, Writing systems

The Japanese writing system consists of three major components — kanji (sinographs), hiragana (cursive syllabary), and katakana (block syllabary). I would argue that rōmaji (roman letters) are a fourth component. We have rehearsed and rehashed their different lexical, morphological, and grammatical functions so often that I don't want to waste time going over them again now. Since we are focusing on katakana in this post, I will merely mention that their main roles are the following:

- transcription of foreign-language words into Japanese

- the writing of loan words (collectively gairaigo)

- emphasis; to represent onomatopoeia

- for technical and scientific terms

- for names of plants, animals, minerals

- often for the names of Japanese companies

(Wikipedia)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink