Old Avestan lexicography

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Hiroshi Kumamoto]

The Last Words of Helmut Humbach (1921-2017)

1

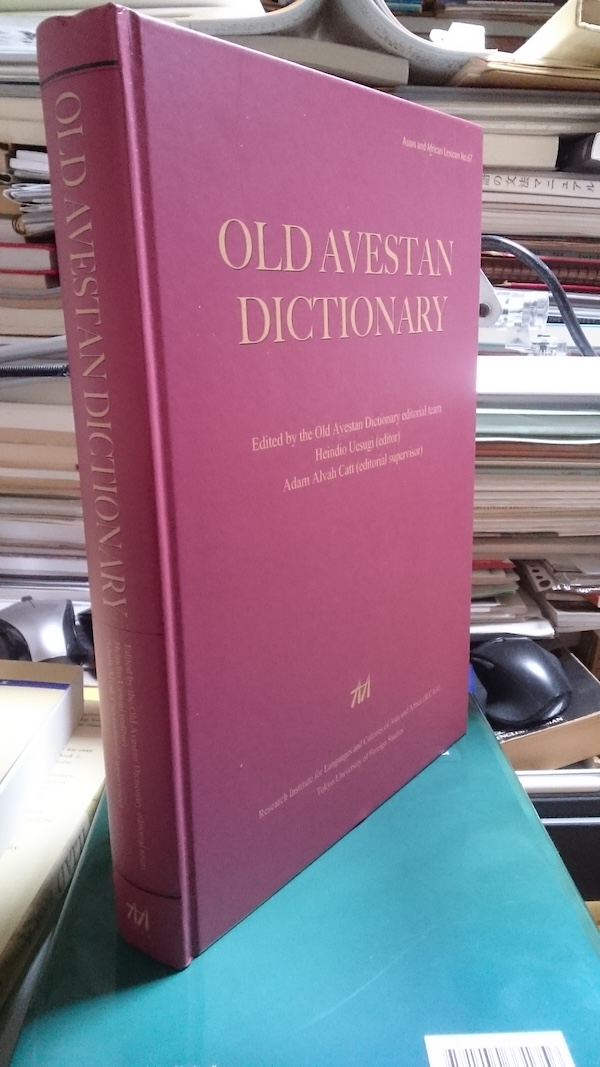

When an eminent classicist, the late Martin L. West published The Hymns of Zoroaster: A New Translation of the Most Ancient Sacred Texts of Iran, London: Tauris, 2010, Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst wrote (Review in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2011, p. 379),"This book (…) comes as something of a surprise, since scholars of the difficult texts in Old Avestan, the oldest known texts in Old Iranian, do not usually emerge out of the blue". Now another surprise is brought by Heindio Uesugi, who edited Old Avestan Dictionary, Tokyo : Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA), 2024 [became available in Feb. 2025] (XXVIII, 404 + VI, 116 pages). Although Adam Alvah Catt at Kyoto University, who is credited as editorial supervisor, is known from his works in Indo-Iranian and Tocharian linguistics, the name of the editor has been totally unknown in the field in Iranian linguistics.

Helmut Humbach (1921-2017) in his lifetime published the translation of the Gathas, the oldest text corpus of the Iranian languages, four times.

- Die Gathas des Zarathustra: Bd. 1: Einleitung; Text; Übersetzung; Paraphrase., Bd. 2: Kommentar, Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1959.

- The Gathas of Zarathustra and the Other Old Avestan Texts: Part 1. Introduction – Text and Translation. part 2, Commentary, Heidelberg:Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1991.

- The Heritage of Zarathushtra: A New Translation of His Gāthās (with Pallan Ichaporia). Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1994.

- Zarathushtra and His Antagonists: A Sociolinguistic Study with English and German Translations of His Gāthās (with Klaus Faiss),Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2010.

Uesugi describes the birth of the book as follows:

The project of creating a dictionary became explicit during the preparation of the aforementioned 1991 translation. However,various circumstances prevented him from completing this dictionary project.

Considering his advanced age, he in turn decided to pass on his stack of materials to me, to whom he entrusted the task of completing the work. Although the skeletal framework of the dictionary was already in place, when looking at the details and through our discussions it quickly became apparent that each entry would require a thorough (re)assessment, and that the project would necessitate considerable time.

Until shortly before his passing, racing against time, we worked relentlessly on the dictionary project, going over my revisions, and spending hours debating each detail. He strove to pass on the methodological approach and insight which would be necessary to complete the work after his passing. The memory of his dedication would keep fueling my determination to complete the project.

After his passing, I was left with a promise to fulfill, the promise to complete the work as best I could, and to publish it in the best way possible. It was an arduous journey. I was blessed to have the support of Adam Alvah Catt, who extended his hand to a traveler in need. He has kindly proofread and supervised the work in its final phase, contributing countless feedback and improvements on the respective drafts. His expertise and contribution have been truly decisive. (Part I, pp. XI-XII).

2

Humbach's 1959 book revolutionalized Gāthā studies. In the words of Jean Kellens,"Humbach had accomplished a Copernican revolution in the field by showing that the Gāthās were not sermons addressed to men, but hymns addressed to gods. That it had been possible to mistake the nature of a text in this way says much about the extent to which its language remained misunderstood". ("The Gāthās, Said to be of Zarathustra", Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, 2015, 44). In order to fully appreciate this "revolution", some background information would be in order.

It was Martin Haug who, in the middle of the 19th century when modern Indology and Iranian Studies were still in their infancy, first discovered that part of the Zoroastrian scriptures called Avesta preserved by the Parsis in West India was distinct in linguistic features from the rest of them, possibly centuries older, written in verse with a variety of meters. He assumed that this part, called Gāthās, represents the words of the prophet, Zarathustra himself, while the language of the rest of the text, which became known as Young (or Younger) Avestan, represents the development in the later stages of the Zoroastrian community. Haug also presented Zarathustra's religion as monotheism, a departure from older polytheistic religion with common Indo-Iranian roots. This view was welcomed by the Parsi community, especially by the reform-minded younger generations, as the Protestant-like rationalism appealed to them in India under British rule. Some of Haug's mistakes, inevitable at this early stage, such as equating Aŋra Mainyu (the Evil Spirit) with Vedic Aṅgiras, were later to be corrected.

Decades later, by the time when Christian Bartholomae (1855-1925) published the still incomparable Altiranisches Wörterbuch (1904) and the translation of the Gāthās (Die Gatha's des Awesta. Zarathustra's Verspredigten ("verse sermons") (1905)) based on it at the height of the Neogrammarian era, the personage of Zarathustra (Zoroaster) seemed well-established in general lines: He lived sometime before the major Achaemenid kings in the 6th century BCE (decades or centuries before according to different views of scholars) somewhere in an Eastern Iranian area (Khorasan, Khwarezmia, or in some minority opinions in Western Azerbaijan). His original milieu was the traditional Indo-Iranian polytheistic world, where he essayed a religious reform promoting monotheistic Ahura Mazdā worship and opposing animal sacrifice. Initially persecuted, and forced to flee from his homeland, he eventually found a patron in King Vištāspa. Under his aegis the Zoroastrian community gained a foothold, and gradually spread to other Iranian speaking areas. However, during the process of expansion the worship of old polytheistic deities crept in, a degeneration as witnessed by the Young Avestan hymns to these deities.

These general lines of Zoroastrian "history" (called by Kellens, ibid. "a tyrannical communis opinio"), were more or less taken for granted for a long time. Most scholarly works in the 20th century, even the acclaimed A History of Zoroastrianism (3 vols.) by Mary Boyce (1975-91), fall basically within this framework. Notable exceptions are the works of H. S. Nyberg (1889-1974) and Marijan Molé (1924-1963), but they did not influence the mainstream much.

3

Helmut Humbach started his work under Karl Hoffmann (1915-1996), "who opened the way to this approach to Zarathushtra's work", according to the dedication of Humbach's 1991 book. In fact, a student of Karl Hoffmann once heard the Master remark that the 1959 book of Humbach was almost as if he had dictated it. In the book of 1959 Humbach endeavored to show and largely succeeded in establishing the fundamental affinity of the Gāthās with the Rigvedic hymns. In spite of this success, if its influence was rather limited, it is perhaps because the translation was too difficult, almost unreadable even to German speakers, and had to be provided with a paraphrase for each verse. To P. O. Skjærvø (Wiley-Blackwell Companion, p. 59) it was "incomprehensible". The book of 1991, on the other hand, gives an incongruous impression. The text and commentary which are linguistic-philologically oriented are preceded by a lengthy introduction which focuses on the legends and myths on Zarathustra in Young Avestan, Zoroastrian Middle Persian (Pahlavi), and even Classical and Islamic sources. The information gathered from these later developments is in principle irrelevant for the understanding of the Gāthās. One has also to be aware that the presentation itself is highly selective. The Zoroastrian tradition actually depicts the prophet as a supernatural of miraculous birth, omniscient, omnipotent, wielding overwhelming power agaist adversaries, and advocating "xwedodah (next-of-kin marriage)". These aspects unsuitable for modern taste were tacitly overlooked.

Kellens (ibid.) laments that progress in grammatical analysis had not necessarily led to the modification of the accepted view that (the Gāthās are) "one of the great sacral expressions of humankind", and that Humbach "let himself be carried away" by this accepted view. Another scholar, the late Stanley Insler (1937-2019) of Yale, who also pursued vigorous comparison of the Gāthās with the Rigveda in The Gāthās of Zarathustra (Leiden: Brill, 1975), concluded his talk on the Gāthās at the South Asia Seminar at Penn not long after its publication by saying (to the effect) that the lofty moral and ethical values of these texts are still worth studying. The most recent translation by M. L. West also echoes similar sentiments. It is curiously reminiscent of the tendencies in the studies of Early Buddhism in the West in the 19th to early 20th century where more emphasis was laid on its moral values than its doctrinal intricacies.

4

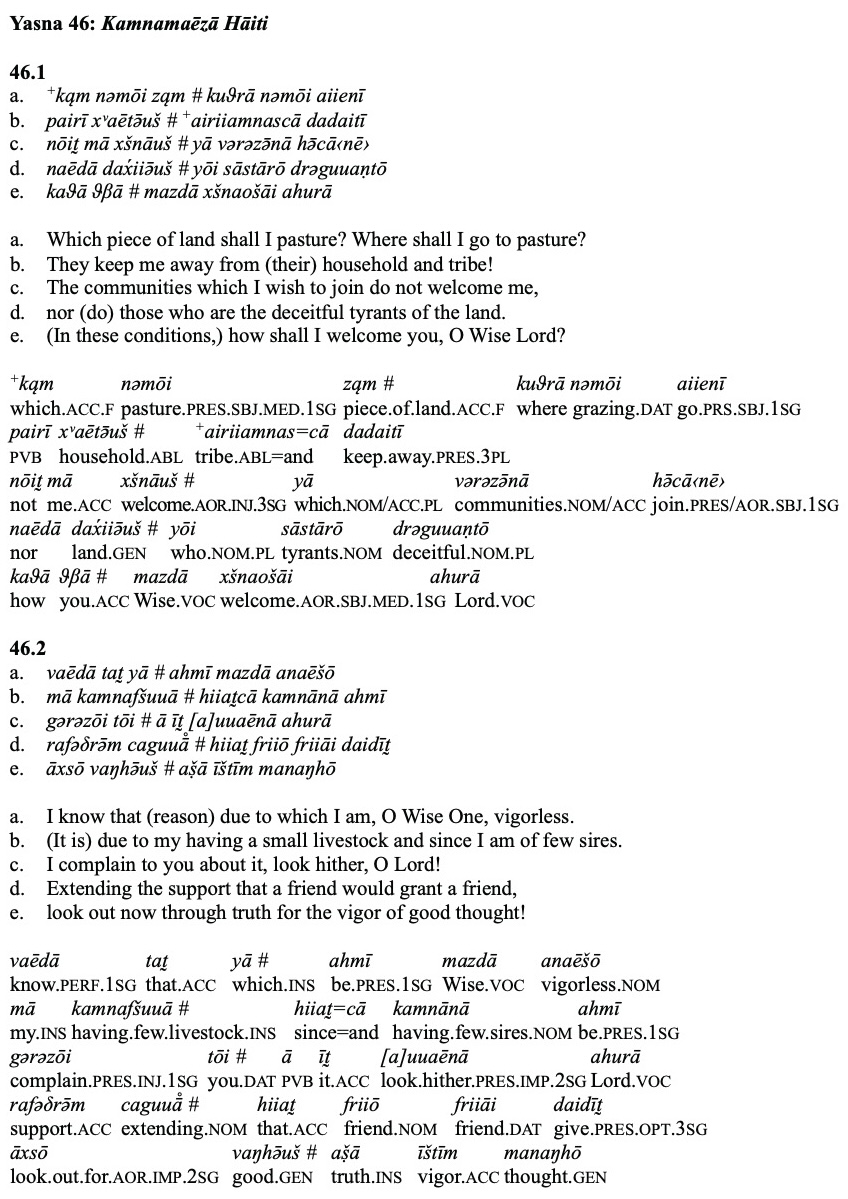

Let us now look at a passage, a line in a verse, to see how the Gāthic exegesis operates.

One novel feature to be most welcome in Part II of Old Avestan Dictionary is the glossed text accompanying the usual text with translation. It makes the author's intention explicit.

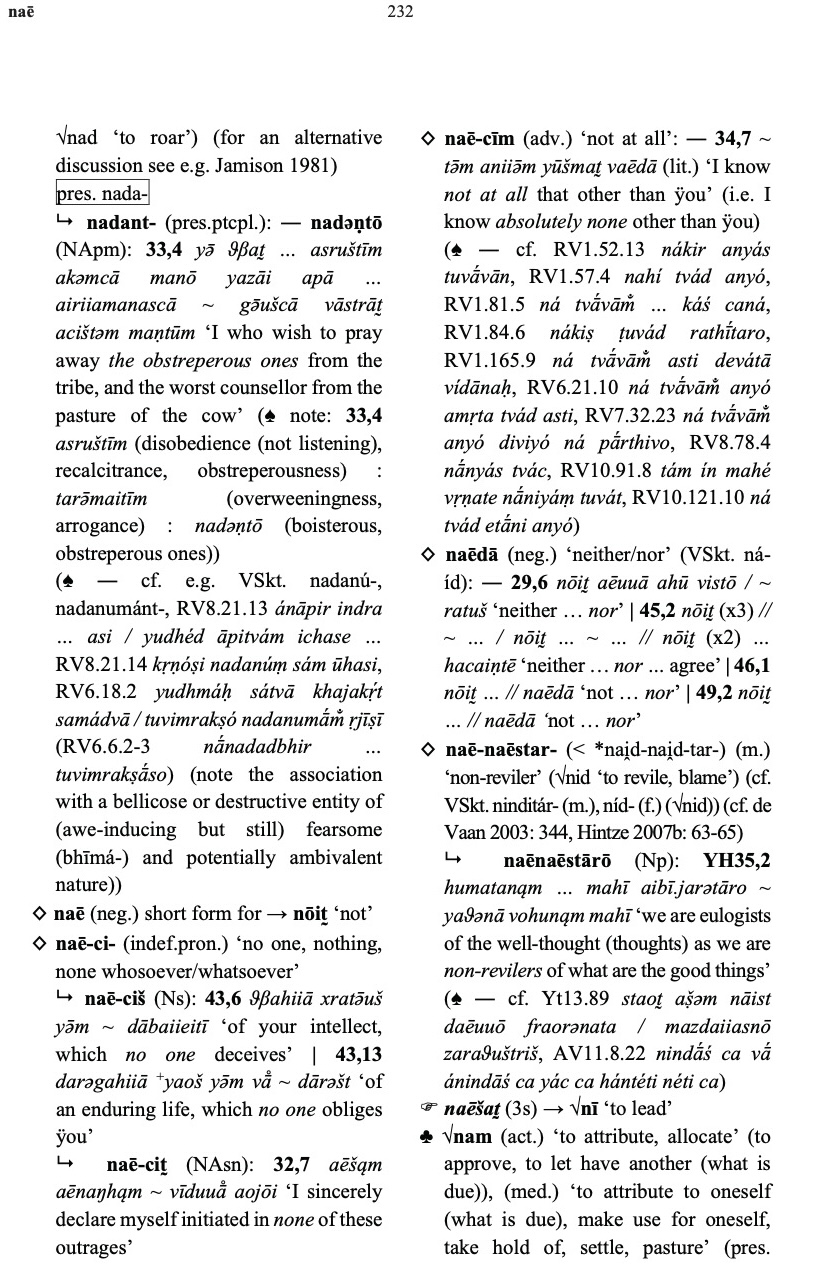

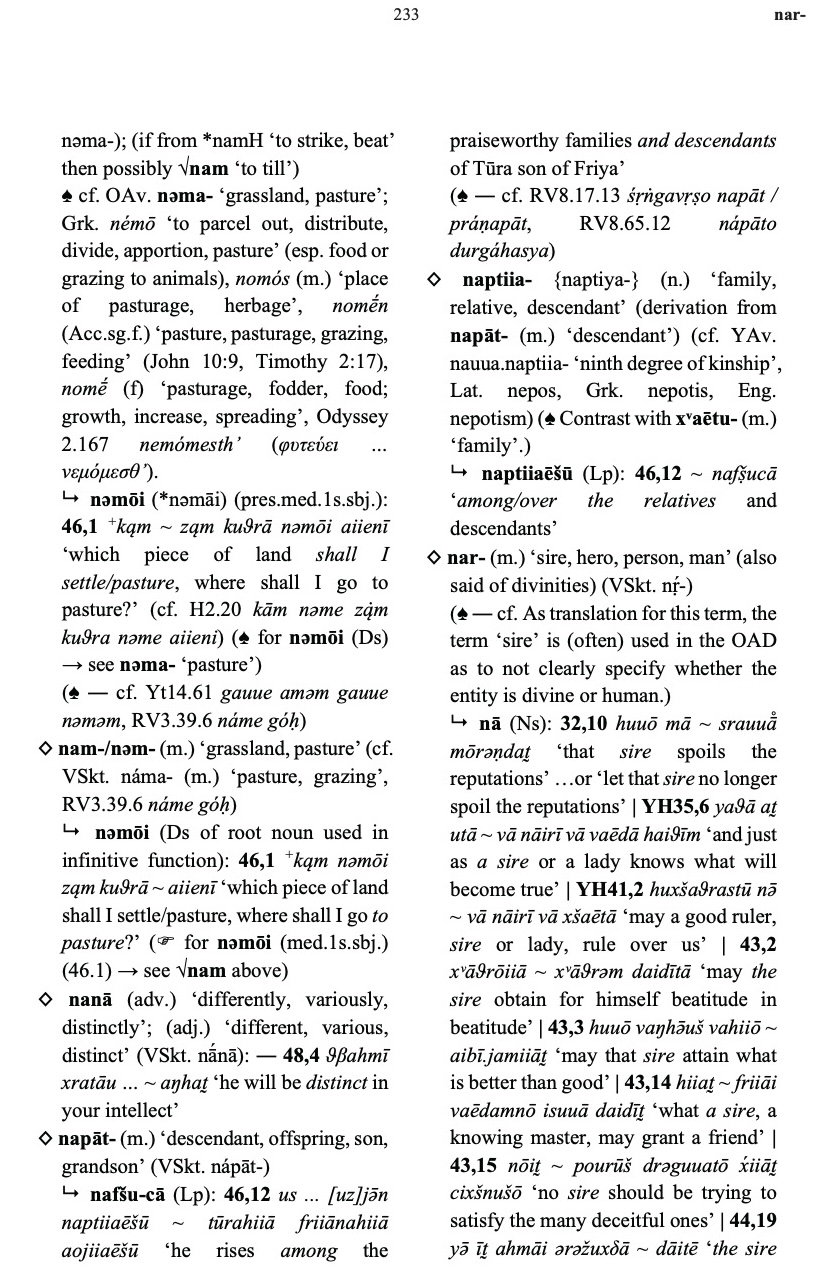

Yasna 46.1a is the key passage (and the sole source) for the Zarathustra legend telling that he was persecuted and forced to flee because of his attempted religious reform. Bartholomae's translation (1905) rendered faithfully in English by Maria Wilkins Smith (Studies in the Syntax of the Gathas of Zarathushtra, Philadelphia: Ling. Soc. of America, 1929, 121), reads: "To what land to flee, whither shall I go to flee?". This is based on the entry nəmōi (col. 1071) as an infinitive in the Altiranisches Wörterbuch. On this word, and on line Y 46.1a, Kellens wrote an article "Yasna 46,1 et un aspect de l'idéologie politique iranienne", Studia Iranica 12, 1983, 143-150 (available here), on which Humbach's 1991 book and this Dictionary remain strangely silent. Kellens demonstrates here that the verbal forms from the root nam– attested in Young Avestan (YAv) are all used with a preverb, apa-, vi- or fra-, and denote a motion ("going") in various ways defined by these preverbs, and that the meaning "to flee" for the simplex is impossible.

The Dictionary sees, on the other hand, the first nəmōi as a finite verb (pres. subj. 1sg, mid.) "to settle/pasture" and the second one a root noun "grassland/pasture" in dat. sg. Now, two homonymous PIE roots *nem– are known; one is "to allot" represented by Greek νέμω "to distribute" etc. and Gothic niman "to take", and the other "to incline to, bend" in numerous forms in Indo-Iranian and Tocharian (Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben, 2. Aufl. 2001, 453). Humbach since 1959 opted for the first root for Y 46.1a nəmōi referring to Gr. νέμομαι "inhabit (a land)", νομός "pasture". In the 1991 book he translated "shall I (go to) graze" for the first nəmōi, but in the commentary maintained the 1959 interpretation that it is "a root noun nam– used in inf. function". Now in the Dictionary the translation and grammatical analysis are finally aligned. However, a new problem arises. The present subjunctive middle 1sg. ending of a thematic verb is –āi (counting as 2 syll.) (Hoffmann-Forssman, Avestische Laut- und Flexionslehre, 2. Aufl., Innsbruck 2004, 195). For nəmōi to be 1sg. subjunctive middle, it would have to be athematic root present, which is unlikely (the Dictionary posits "pres. nəma-"). Skjærvø, who translates "To what earth/ground am I bending? Where shall I go to (find) a grass land? (The Spirit of Zoroastrianism, New Haven: Yale UP, 2011, 125) correctly indicates, in his Old Avestan Glossary (available online), that nəmōi is "Ind.1S Mid", not subjunctive. But the following aiienī "I shall go" being clearly subjunctive, one would, if it is a finite verb, expect a subjunctive 1sg. also.

The word for "pasture" in Avestan is either gaoiiaoiti– (Ved. gávyūti-) or vāstra– (W. Geiger, Ostīrānische Kultur im Altertum, Erlangen 1882, 344, n. 3). The first is attested only in YAv., but the second is also found in Old Avestan (Dictionary 338). This does not exclude another term for "pasture", as no language is without synonyms. But the Vedic form adduced in support of the claim that the second nəmōi means "pasture" is not quite a happy one. RV 3.39.6b náme góḥ is a problematic phrase with no convincing solution. Jamison / Brereton, The Rigveda, OUP 2014, has "in the 'bend of the cow'" without explanation. In fact Hermann Oldenberg, Noten I, 1909, 249, explicitly warned that to explain náme with Gr. νομός is highly risky ("höchst gewagt").

A feature difficult to justify in the Dictionary is that the entry for the verbal root nam– is given the definition ‘to attribute, allocate’ (to approve, to let have another (what is due), (med.) ‘to attribute to oneself (what is due), make use for oneself, take hold of, settle, pasture’ , as if all of these meanings are found in the text passages, while the only example quoted under it is the first nəmōi as discussed above. It looks as if the list of meanings were simply lifted from other sources such as Frisk's Griechisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch (under νέμω, "aus-, zuteilen, sich aneignen, besitzen, bebauen, weiden, abweiden, verzehren").

Practically every line of the Gāthās contains uncertainties. The Gāthā interpretation resembles completing a jigsaw puzzle where each piece is uncertain but not impossible. That is the reason no seriously attempted translations agree with one another.

5

The beautiful hardcover book of Old Avestan Dictionary can be obtained free of charge within Japan from the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa for scholarly (that is, non-commercial) purposes. It does not circulate in the book market, and will not appear on Amazon or ABE books or any such sites unless someone sells it second-hand. I don't know the overseas shipping policy of the Institute. Either writing directly to them (in Japanese) or contacting Prof. Adam Catt at Kyoto University is recommended.

The pdf copy is freely available for download here. Click the file name below the preview window (the book itself and an errata sheet). It has been announced that the errata will be renewed. Check the site from time to time.

Selected readings

- "Old Avestan Dictionary", languagehat (2/20/25) — lengthy, lively, learned discussion

- "An Avestan manuscript with Gujarati translation" (5/18/14)

- "So spoke Zoroaster: camels and ancient Sinitic reconstructions" (1/13/21)

- "Indo-European religion, Scythian philosophy, and the date of Zoroaster: a linguistic quibble" (10/9/20) — with an extensive bibliography

Martin Schwartz said,

March 11, 2025 @ 9:42 pm

As someone for whom the understanding of the Gathas

has become an obsession, I thank Professor Kumamoto for this most interesting post.

Martin Schwartz

Andreas Johansson said,

March 12, 2025 @ 2:12 am

Now I know very little about Zoroastrism, but one might have thought the Parsis themselves would have known if the gathas were sermons or hymns?

Stephen Goranson said,

March 12, 2025 @ 7:47 am

I also know little about Zoroastrianism, but read that the meaning of parts of the liturgy had been lost, without being thought to reduce its sacredness, which reminds me of another memory: when an old composer was asked how a listener could understand when a choir was singing multiple texts at once, the reply was that God understands.

Rodger C said,

March 12, 2025 @ 11:55 am

My first question when reading this: What sort of Japanese name is Heindio?

Chris Button said,

March 13, 2025 @ 8:15 am

Is the use of cursive ϑ for θ standard practice? I note Cheung also uses ϑ in his "Etymological Dictionary of the Iranian Verb".

Nelson Goering said,

March 13, 2025 @ 11:27 am

"Is the use of cursive ϑ for θ standard practice?"

Yes, this is very common. You'll find it in Bartholomae's classic dictionary, in Hoffmann & Forssman's excellent grammar, in Kellens' Liste du verb avestique, Hintze's edition of the Yasna Haptaŋhāiti, and any number of other places. It's not universal, and you'll certainly see a normal θ even in works primarily on Avestan, but that seems less standard.

I really don't know why, though. Maybe it's just that the cursive ϑ just seems to fit the aesthetic of the (very beautiful) Avestan script so well?

Chris Button said,

March 14, 2025 @ 11:48 am

ϑ is a lot nicer!

Sean said,

March 23, 2025 @ 10:24 pm

German publishers such as Teubner tend to prefer fonts with different forms of kappa and theta than Anglo publishers. Since Avestan scholarship in Europe was founded by Germans, maybe its still customary to use fonts that a German publisher would accept?

IIRC Rüdiger Schmitt's dictionary of Old Persian uses a theta that could be drawn without lifting your pen from the paper.