New article in the Wall Street Journal:

"‘The Greatest Invention’ Review: Written communication was a remarkable breakthrough, made in many different places and at different times." By Felipe Fernández-Armesto, WSJ (March 11, 2022)

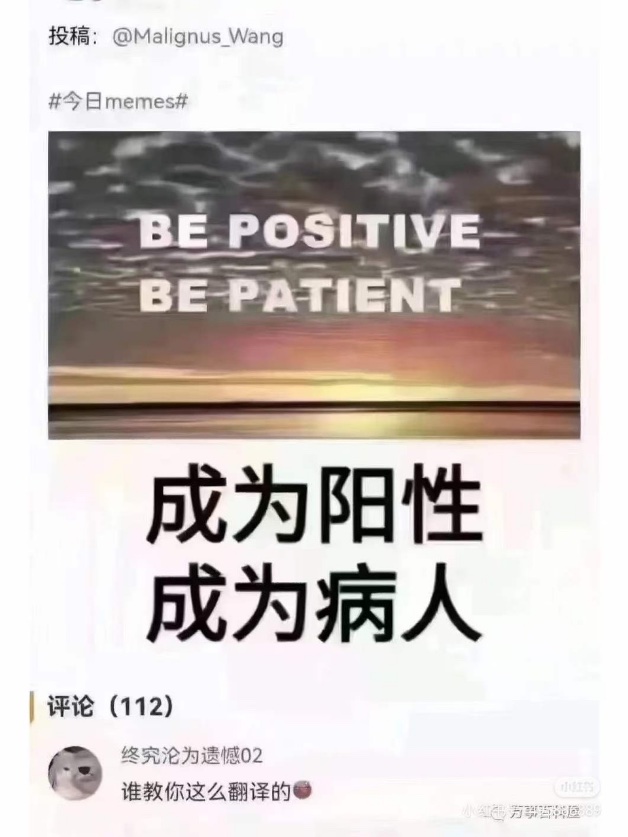

There are a number of assumptions and speculations packed into just this title. When we look at the book itself, we find far more. In the wake of the sensationalism and hype over the recently published Kingdom of Characters, lauded in countless reviews, we need to take grand claims about the nature and purpose of writing with a great deal of caution and a pinch of salt. Fernández-Armesto's review is appropriately critical.

The review begins:

Theuth, the eager god, was proud of having invented writing. “It will,” he promised King Thamus, “make the Egyptians wiser and improve their memories.” Thamus, in Plato’s account of the myth, disagreed. “Your invention will make readers forgetful. They will stop trying to remember. They will absorb words without wisdom, data without learning, information without knowledge, and trivia without truth.”

The king’s criticisms eerily foreshadow current animadversions about the internet. Even when applied to writing, they were not entirely misplaced. Intellectuals should take them as a warning against overrating the scribe’s art. We tend to assume that the function of text is to perpetuate creativity, imagination and science. Really, however, writing began, in all the cases we know, by serving humdrum purposes: recording prices, inventories and tax returns. For most of the past, what was truly great was easily memorable: the epics, the myths, the revelations of the gods.

Read the rest of this entry »