The Origin(s) of Writing

« previous post | next post »

New article in the Wall Street Journal:

"‘The Greatest Invention’ Review: Written communication was a remarkable breakthrough, made in many different places and at different times." By Felipe Fernández-Armesto, WSJ (March 11, 2022)

There are a number of assumptions and speculations packed into just this title. When we look at the book itself, we find far more. In the wake of the sensationalism and hype over the recently published Kingdom of Characters, lauded in countless reviews, we need to take grand claims about the nature and purpose of writing with a great deal of caution and a pinch of salt. Fernández-Armesto's review is appropriately critical.

The review begins:

Theuth, the eager god, was proud of having invented writing. “It will,” he promised King Thamus, “make the Egyptians wiser and improve their memories.” Thamus, in Plato’s account of the myth, disagreed. “Your invention will make readers forgetful. They will stop trying to remember. They will absorb words without wisdom, data without learning, information without knowledge, and trivia without truth.”

The king’s criticisms eerily foreshadow current animadversions about the internet. Even when applied to writing, they were not entirely misplaced. Intellectuals should take them as a warning against overrating the scribe’s art. We tend to assume that the function of text is to perpetuate creativity, imagination and science. Really, however, writing began, in all the cases we know, by serving humdrum purposes: recording prices, inventories and tax returns. For most of the past, what was truly great was easily memorable: the epics, the myths, the revelations of the gods.

India constitutes a good case history of the rejection of writing by a highly advanced civilization that was aware of this technology but resisted its seductions for fear that it would dull the mind. The Vedas, the Upanishads, Mahabharata, Ramayana — all these monuments of thought and literature — were first composed and transmitted long before they were written down. Even the extremely terse propositions of Pāṇini's (ca. 5th c. BC) Aṣṭādhyāyī ("eight chapters"), arguably the world's first grammar, consisting of 3,959 verses on syntax, semantics, and other aspects of linguistics, were orally transmitted from the very beginning.

It is sort of like the samurai Giving up the Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879 (Noel Perrin's great book) or Middle Easterners rejecting the wheel in favor of their tried and true ship of the desert, the camel (see Richard Bulliet's seminal social history on that topic).

Here is an enigmatic object that has fascinated me for more than half a century:

One side of the ‘Phaistos Disk,’ a tablet containing hieroglyphic symbols from Crete, ca. 2000 B.C.

This is clearly meant to convey information, if not language. It even has divisions that break up the "text" into "words" or "phrases", and it is written with symbols that are echoed in other circum-Mediterranean "scripts". Does it represent language? As Chinese scholars are fond of saying when stumped by a philological problem, dàikǎo 待考 ("awaiting verification").

Selected readings

- "'The world's oldest in-use writing system'?" (5/12/12)

- "Writing: from complex symbols to abstract squiggles" (6/11/19)

- "Tel Lachish and the origin of the alphabet" (4/26/21)

- "Tel Lachish and the origin of the alphabet" (12/27/21)

- "Memorizing a thesaurus" (10/28/20)

- "The stupendous powers of memorization in the Indian tradition" (10/23/20)

- "What happened to the spelling bee this year?" (10/21/20)

- "Spelling Bee 2019" (5/31/10)

- "The worldly sport of spelling" (6/2/18)

- “Spelling bee champs” (6/1/14)

- “Spelling bees and character amnesia” (8/7/13)

- “Brain imaging and spelling champions” (8/7/15)

- “Spoken Sanskrit” (1/9/16)

- "Once more on the mystery of the national spelling bee" (5/27/16)

- "Spelling bees in the 1940s" (7/10/16)

- "Yet again on the mystery of the national spelling bee" (6/5/17)

- "Character Amnesia" (7/22/10)

- "Prehistoric notation systems in Peru, with Chinese parallels" (4/17/21)

[Thanks to June Teufel Dreyer, JJ Tkacik, and Mark Metcalf]

Arthur Baker said,

March 19, 2022 @ 3:00 pm

Surely the invention of language itself would necessarily be a greater invention than writing, and arguably humans' greatest of all? Somebody, way back, had this bright idea: look, we seem to be able to make a wide variety of noises, why don't we string some of these noises together and devise sequences to represent things and actions? Then we can communicate about times that aren't now, places that aren't here, people and phenomena we've never met, and all sorts of other stuff. Brilliant. If I could borrow Doctor Who's Tardis for a while, I'd like to go back to that moment when people invented spoken words and congratulate them. As for writing, yeah, OK, very good, but that was only an enhancement of something that already existed – langauge.

Philip Taylor said,

March 19, 2022 @ 4:36 pm

"Somebody, way back, had this bright idea: look, we seem to be able to make a wide variety of noises, why don't we string some of these noises together and devise sequences to represent things and actions? Then we can communicate about times that aren't now, places that aren't here, people and phenomena we've never met, and all sorts of other stuff".

But in order to have that "bright idea", language would already have had to be invented, would it not ? Had language not already have been invented, the idea would have been inexpressible and therefore unthinkable. N'est-ce pas ?

Ted McClure said,

March 19, 2022 @ 4:41 pm

See Yuval Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2011), Part I.

Scott P. said,

March 19, 2022 @ 4:41 pm

Here is an enigmatic object that has fascinated me for more than half a century:

I have a dirty little secret: I have a strong suspicion that the Phaistos Disc is a fake.

Gene Anderson said,

March 19, 2022 @ 4:42 pm

Language was evolved, not invented. Like your arms and legs. All these complex communication systems are genetically coded. Specific languages developed very slowly over time, but the language ability and verbal/gestural symbolic communication evolved as surely as bird songs. Plenty of evidence: all people everywhere have more or less equally complex languages, even people born with serious brain damage acquire it, and nobody seems to be able to change it radically (except simplification in "pidgin" languages). Then language changes are very slow and gradual, not sudden. Actually, when you look at it, even inventions were usually slow and gradual matters, the final key "invention" being usually developed independently by two or more people at one time, because the field was ready for it.

Polyspaston said,

March 19, 2022 @ 5:25 pm

As I go on, I become more and more impressed by how utterly unhelpful the story about Thoth and Thamus really is.

In Egypt, the earliest uses of writing appear to be to do with labelling things – either captions to images (as on the Narmer Palette), or actual objects/goods (the ivory tags from tomb U-j at Abydos). I'm extremely sceptical that *memory* had much to do with the early development of Egyptian writing, which seems more to relate to communicating what is not immediately self-evident, or perhaps to a level of social complexity where the value of an image can no longer be self-evident to all who see it. Presumably to begin with, the pictographic nature of the hieroglyphic script made reading it fairly straightforward, though this almost certainly didn't last long, given that the sign inventory of the First Dynasty was very large but also, if I recall correctly, rather variable, with each reign being accompanied by the development of new signs and the abandonment of old ones. If I recall this correctly, I would suggest this might point to the use of writing to *restrict* access, rather than to enhance communication.

The second and perhaps more important point is simply that writing was plainly not used as a method of recording material for *reading* until much later in Egypt. The first sentence in hieroglyphs doesn't appear until the reign of Peribsen (c. 2660-2650 BCE?) in the 2nd Dynasty, c. 250 years after the first attested writing from Egypt. The first lengthy, continuous monumental inscriptions don't appear until the late 4th Dynasty at the earliest (c. 2450 BCE?), and the first works of written literature, stricto sensu, don't appear until early in the 12th Dynasty (perhaps in the reign of Senusret I, c. 1920-1875 BCE). Its not until the later Middle Kingdom that we start having examples of things like compilations of medical texts on papyrus, which might have been intended for consultation. We do find compilations of funerary texts earlier on, for example, the walls of the pyramids of the 5th and 6th Dynasties, but the location, layout, and position of these in, e.g., burial chambers, make clear these were not intended for consultation. They may have been copied from papyrus copies, of course, but whether these were compiled especially for copying or as genuine "ritual books" is a bit more complex, as is the relationship between ritual book and performance (which is not necessarily at all straightforward – Taiwanese ritualists for instance, often appear to read ritual scrolls while actually reciting the text from memory -see Schipper in Journal of Asian Studies 45/1 (1985)).

There's also a fundamental problem that reading is still a matter of using the memory. At a basic level, it requires a knowledge of the correspondence of signs to the things they represent (e.g., of letter-forms to the phonetic sounds they represent in an alphabet). For "deep" orthographies, such as English, in practice it often means knowing the correspondence between the visual form of the whole word and its verbal pronunciation, or at least of a vast inventory of highly contextualised potential pronunciations and of sign-groups with corresponding sounds. Given that the earliest writing systems both had large sign inventories and a highly pictographic form, I'm dubious it would have saved the memory much, even if they had been used to actually store information for retrieval in the way this idea implies.

Has the oral-memorial transmission of the Upanishads, Vedas, etc, been actually tested, or is this something which has been asserted by the tradition, and taken at face-value? Given, to take one example, the findings of Parry and Lord on oral performance, I would suggest it's perhaps worth asking at least what sort of transmission we are actually talking about.

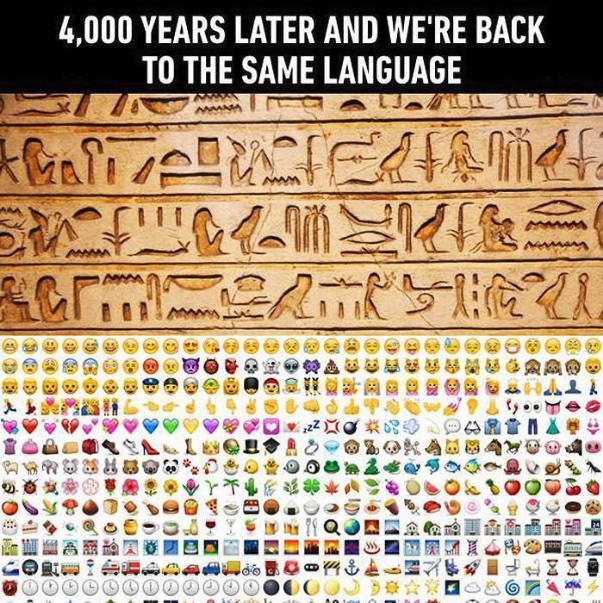

Finally, I don't really see why we have to keep insulting the complexity and subtlety of the hieroglyphic system by comparing it to emoji.

Victor Mair said,

March 19, 2022 @ 7:35 pm

@Polyspaston

I quite agree with you about the false analogy between hieroglyphics and emoji. One of the reasons I put that lame meme at the end of the post was in hopes that someone would shoot it down, for which thank you. Another reason is that at least one prominent professor of Chinese literature has been drawing parallels between Sinographs and emoji, and seems unable to see the fundamental differences between the two. So this has to be brought to the surface and straightened out.

Terry Hunt said,

March 19, 2022 @ 11:11 pm

Scott P. – Any number of people have suggested this, but (having delved into the subject), I disagree.

* The disc was reportedly discovered in a datable context by a recognised (if minor) archeologist, so to begin with, he would have had to have been committing a hoax – for what reason?

* Since the discovery of the disc, other artifacts from the same era have been discovered with some of the same signs, so (some of) the disc's signs are not a modern invention, nor can they have been copied from then-undiscovered genuine artifacts.

Among those artefacts, some (e.g. a set of earrings) also arrange their signs into a spiral, confirming that this was a motif of the era.

I have my own conjectures about the disc. Since I am an armchair amateur they are likely worth nothing, but they include:

* The disc is a discarded trial piece, perhaps by an apprentice or similar (else it would be better produced – clay is, after all, cheap and plentiful, and we know the signs were impressed using reusable dies, a form of moveable-type printing).

* The disc is an aide memoire for a (presumably important) story, rather than a full text.

* Some of the symbols common at "sentence beginnings" signify social ranks (perhaps followed by names) of persons, culturally equivalent to something like "Sir" (i.e. a knight or warrior), "Lady", "Squire" (or other servant), "Merchant", "Slave".

* The "pedestrian" sign signifies an action rather than a person.

Peter Grubtal said,

March 20, 2022 @ 1:02 am

Terry Hunt

But why do the authorities responsible refuse to allow a thermoluminescence test?

Arthur Baker said,

March 20, 2022 @ 4:12 am

Philip Taylor, as Gene Anderson says, language wasn't invented whole, as we know it now, it evolved. Of course. But there must have been a moment when, for the first time, a person strung together some arbitrary non-onomatopoeic sounds, thus making a word, and pointed to something to suggest "the string of sounds I'm making now represents the thing I'm pointing to".

It might have been a rock, a bird, an animal, a place, a body part. We'll never know. But in that moment of the production of the first word in human existence, was the seed of language. It was the invention point. Thence, language needed expansion to what we know now, and it continues to grow and change and evolve. But that has to have been the moment of invention.

Philip Taylor said,

March 20, 2022 @ 4:53 am

« For "deep" orthographies, such as English, in practice it often means knowing the correspondence between the visual form of the whole word and its verbal pronunciation, or at least of a vast inventory of highly contextualised potential pronunciations and of sign-groups with corresponding sounds » — is this necessarily true ? Do congenitally profoundly deaf people make any use of verbal pronunciations, highly contextualised potential pronunciations or corresponding sounds when reading, or do they map directly from visual appearance to concept without passing through sound at all ? And if the latter, is it not possible that at least some persons with normal hearing might (be able to) do likewise ? I am thinking in particular of those highly skilled at speed-reading : might they too go directly from visual appearance to concept without passing through sound ?

David Marjanović said,

March 20, 2022 @ 5:51 am

In addition to what Terry Hunt said, the symbols are pretty clearly continuous with "Cretan hieroglyphics" and the Linears, they're just less stylized.

What do you mean? They are being learned in oral-memorial transmission right now. And they're not learned like epics; precisely correct pronunciation is believed to be essential to their function as prayers/hymns/rituals.

That's why the texts are practically devoid of variants, very much unlike the New Testament for example.

One thing that makes learning the Vedas easier than the same amount of Iliad or Odyssey is that the tune of the Vedas is entirely determined by the positions of the word stresses. Which words can go where is constrained not only by the meter, but also by the tune of each verse which most people probably learn more easily than the words themselves.

(Too bad the tunes of the Iliad and the Odyssey were lost at some point after the 9th century. But given what we do know about Ancient Greek music, the tunes were probably not completely determined by the stresses.)

The low number of distinct signs strongly suggests a syllabary. That doesn't mean there can't be any logograms at all on the disc – there are some in Linear B – but they clearly don't make up the bulk of the text. Given that, and again Linear B, I don't expect logograms for verbs.

I offer the Viennese Theory of Everything: "because they're stupid".

I'm not sure about that. Writing was probably unknown in India before contact with the Persian empire. Pāṇini almost certainly knew about writing (in Aramaic and perhaps Greek), and preferred to continue the tradition rather than write India's first book; but the composers of the scriptures did not, and those of the epics may not have either.

Pre-Roman Gaul could be a better case. All the way into Switzerland, the druids knew the Greek letters and used them for mundane purposes, but the really important stuff was instead learned by heart (aided by various tricks, e.g. everything seems to have come in threes). Part of the motivation was to preserve the status of the druids as keepers of secret knowledge.

David Marjanović said,

March 20, 2022 @ 6:23 am

A glimpse of Indian methods of exact memorization of scarily long texts without any writing.

in other words Hanlon's Razor.

Trogluddite said,

March 20, 2022 @ 7:30 am

@Philip Taylor: "…map directly from visual appearance to concept without passing through sound at all ? […] is it not possible that at least some persons with normal hearing might (be able to) do likewise ?"

Many autistic people categorise themselves as "picture thinkers", completely lacking any kind of "inner voice" as a medium for reasoning. My impression is that, as with the autism "spectrum" itself, we each (autistic or not) occupy our own place within a multi-dimensional space bounded by "word thinking", "picture thinking", etc. and even "aphantasic thinking" (requiring no "imagined medium" at all). One's place within this space likely changes with the task at hand; in particular the task of arranging thoughts which we need to communicate to others – "picture thinkers" often speak of a laborious process of "translation" between mind's-eye and words.

"Picture thinking" is extremely baffling and fascinating to me, as I have what is sometimes called the "hyperlexic" form of autism. My over-reliance on "word thinking" has its own downsides; my lack of a mind's eye and difficulty conceptualising physical gestures are such that I often have to insist that people "tell don't show" – much to the frustration of my PE teachers and Boys Brigade drill instructor!

Victor Mair said,

March 20, 2022 @ 8:24 am

@Troggludite

Cf. "Aphantasia — absence of the mind's eye" (3/24/17)

Victor Mair said,

March 20, 2022 @ 9:03 am

@suburbanbanshee

I think they are what Dr. Dzwiza calls them: "magic signs".

Philip Taylor said,

March 20, 2022 @ 9:54 am

As the aphantasia thread is now closed for comments, perhaps I might add a short one here, in answer to the gedankenexperiment> posed therein : "Imagine the table where you've eaten the most meals. Form a mental picture of its size, texture, and color. Easy, right? But when you summoned the table in your mind's eye, did you really see it? Or did you assume we've been speaking metaphorically?".

I saw it, in my mind's eye — the contour at the edges of the top, the colour, the (stained) wood, the legs, even how the legs are joined to the top. Basically I saw this, but with the two hinged leaves folded down and with no chairs.

Scott P. said,

March 20, 2022 @ 10:03 am

* Since the discovery of the disc, other artifacts from the same era have been discovered with some of the same signs, so (some of) the disc's signs are not a modern invention, nor can they have been copied from then-undiscovered genuine artifacts.

None with stamped signs, right? The whole point of developing such a system (which is incredibly precocious — I don't know of any other attempt at something approaching 'moveable type' for thousands of years) would be to produce rapid, standardized, duplicate texts. There would be a time savings only if thousands, maybe tens of thousands, of texts were produced with the stamps. And we only found one?

* The disc is a discarded trial piece, perhaps by an apprentice or similar

Anything is possible, of course, but if the disc were the only one of its kind produced, the chances of us finding it, let alone complete, would be vanishingly small. The chance of its preservation must be at best one in a million. So the chance of it being a forgery has only to be two in a million for that to be the most likely explanation.

Jim Unger said,

March 20, 2022 @ 10:44 am

I would remind readers of John DeFrancis's distinction between partial and full writing systems. Human beings improvise and use ad hoc visual signs even today. A collection of such ad hoc signs that two people share can be called a writing system but only a partial one because it can only represent the ad hoc collection of words or phrases the users have agreed upon. A full writing system, on the other hand, can in principle represent any word or phrase of the language it was designed for: it is full because it is coextensive with the possible output of speakers of the language.

DeFrancis argued that full writing systems appear to have come into existence ab ovo only three times in human history: once in Mesopotamia; once in China; and once in Meso-America. All other full writing systems have been developed by people who had one of those models to copy from. (I have lately seen claims of a very early Egyptian script predating Sumerian: if they are valid, that would raise the total to four.) From this perspective, the statement at the head of this article is just wrong.

Victor Mair said,

March 20, 2022 @ 1:42 pm

Below is a recent article on the Phaistos Disk. Some of the symbols have been found on pottery.

https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2021/11/phaistos-disk

If you're interested in the Phaistos Disk, this is a must read.

AntC said,

March 20, 2022 @ 8:26 pm

I have a strong suspicion that the Phaistos Disc is a fake.

A better candidate for fakery would be the Antikythos mechanism, about 87 BC "works with similar complexity did not appear again until … the fourteenth century." [wp]

If it was a navigational aid, surely every Greek ship carrying valuable cargo would have come equipped with one, and we'd find similar in other wrecks.

"it must have had undiscovered predecessors" [wp again] — where are they? where are gears and axles to that level of accuracy? They must have been made of metal; something of them should have survived.

John Swindle said,

March 21, 2022 @ 3:35 am

Regarding suburbanbanshee's question about a Roman magic gem, yes, they're just magical symbols, but some of them could be seen as Chinese. For example, forms of 日、曰、干、一、丁、口、目、夫、中、卅、入、米。Some could also be from Greek or Roman alphabets; the sequence "EZ" stands out. I imagine the magician making up symbols and asking his mother, "Mommy, what does this say? Now what does it say?"

Victor Mair said,

March 21, 2022 @ 7:49 am

From Jane Hickman:

I have seen the Phaistos Disk many times in the Heraklion Museum in Crete. Although some still think it is a forgery, more archaeologists , including a friend of mine who does Linear B, now think it is real. It is an amazing artifact, in perfect condition. Wish another object, with at least a few of the same symbols, could be found.

/df said,

March 21, 2022 @ 10:12 am

"A better candidate for fakery would be the Antikythos mechanism…"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antikythera_mechanism#Similar_devices_in_ancient_literature

A good explanation for the lack of replicas is that such a device was far too precious and expensive to put on a ship, except, say, as part of a treasure haul for a triumph.

Surely the emoji gag would have been even more accurate with Chinese characters rather Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were at least partially a phonetic script?

Andrew Usher said,

March 21, 2022 @ 9:24 pm

Actually, the Antikythera mechanism is a very unlikely candidate for being forged as it is so unlikely anyone with access would have the knowledge required, and maybe no one at all today would. The Phaistos Disc is a much more reasonable thing for an archaeologist to fake, but I have no opinion about that and defer to the consensus.

I have never doubted that writing is indeed 'the greatest invention', even if its anonymous inventors never dreamed of the uses to which it would eventually be put. Any fears that writing would dull the mind were very badly misplaced, and it rather enhances the mind by freeing it from excessive memorisation. And India is actually a good example of this – where did their continuance of an elaborate oral tradition get them? Quite nowhere, and it has crippled the minds they have that might have been great. There is hardly a more obvious contrast between the fact that Indians educated in India have achieved basically nothing, while Indians educated in America or England have produced a decent share of the world's intelligence.

Though I haven't particularly studied the question, I find it incredible that Panini was composed without writing, even if it was converted into oral form. Written information is an absolute essential for scholarship, and not only for cultural reasons.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com

Peter Grubtal said,

March 22, 2022 @ 1:16 am

Andrew Usher –

a well-needed dash of cold reason to counter Thamus' objection.

I don't think you're being fair to India, ancient or modern, though: in modern times in maths and science there have been major contributions from India-educated individuals: Bose and Raman spring to mind without even trying. And of course we owe much to early Indian mathematics, zero, Arabic numerals (called Indian numerals in Arabic), a lot of trigonometry.

You could compare with Islamic countries where it was prestigious to learn the Koran by heart. But can one say it was totally negative? : there were serious contributions to science by Islamic scholars in the medieval period.

Terry Hunt said,

March 25, 2022 @ 4:40 am

Belatedly further to the discussions of human language development above, my copy of this week's New Scientist magazine has just dropped on the mat, and the cover article is billed as "How humans learned to speak: The accidental origins of our greatest innovation".

The actual article is 'Playing with words' by Morten H. Christiansen and Nick Chater (New Scientist 26 March 2022 Vol. 253 No.3379, pp38–41 — presumably it's also accessible online).

I haven't started reading it yet, but it will doubtless be of some interest to many here. It's appearance is linked to their new book The Language Game.