Just out, a stimulating new book from Brill (2020):

Mareshi Saito. Kanbunmyaku: The Literary Sinitic Context and the Birth of Modern Japanese Language and Literature. Series: Language, Writing and Literary Culture in the Sinographic Cosmopolis, Volume: 2. Editors: Ross King and Christina Laffin; translators: Alexey Lushchenko, Mattieu Felt, Si Nae Park, and Sean Bussell

From the author's Introduction, p. 1:

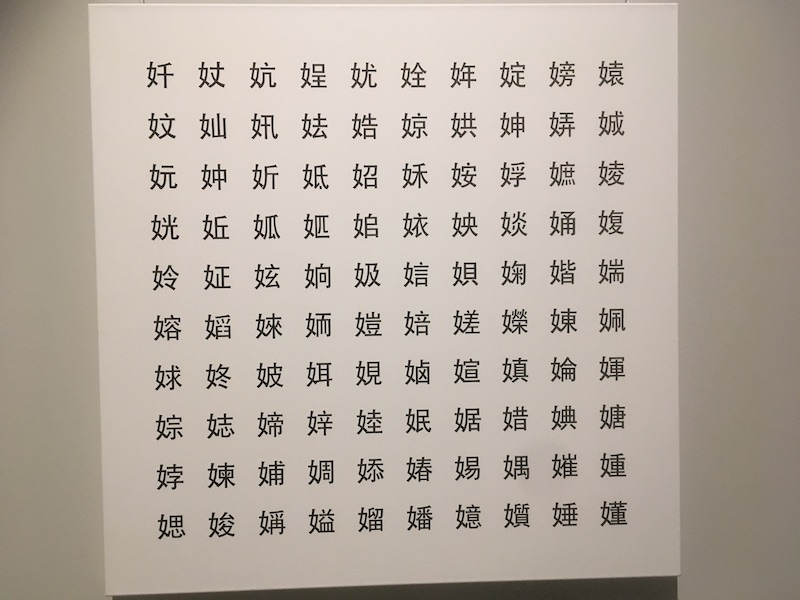

The chief aim of this book is to consider the language space of modern Japan from the perspective of what I am calling kanbunmyaku 漢文脈 in Japanese, translated here as “Literary Sinitic Context.” I use the term “Literary Sinitic”* to designate what is often referred to as “Classical Chinese” or “Literary Chinese” in English, wenyan 文言 in Mandarin Chinese, kanbun 漢文 in Japanese (sometimes referred to as “Sino-Japanese” in English), and hanmun 漢文 in Korean. The Context in Literary Sinitic Context translates the -myaku of kanbunmyaku, and usually implies a pulse, vein, flow, or path, but is also the second constituent element of the Sino-Japanese term bunmyaku 文脈 meaning “(textual, literary) context.” I use the term Literary Sinitic Context to encompass both Literary Sinitic proper, as well as orthographic and literary styles (buntai 文体) derived from Literary Sinitic, such as glossed reading (kundoku 訓読) or Literary Japanese (bungobun 文語文), which mix sinographs (kanji 漢字, i.e., “Chinese” characters) and katakana. In addition to styles I also consider Literary Sinitic thought and sensibility at the core of which lie Literary Sinitic poetry (kanshi 漢詩) and prose (kanbun 漢文), collectively termed kanshibun 漢詩文.

*For the term “Literary Sinitic,” see Victor H. Mair, “Buddhism and the Rise of the Written Vernacular,” Journal of Asian Studies, 53.3 (August, 1994), 707-751.

Read the rest of this entry »