The complexification of the Sinoglyphic writing system continues apace

« previous post | next post »

Many innocent observers have been snookered by the Chinese Character Simplification Scheme and the relatively small amount of characters that were reduced in the number of strokes with which they were written or were abolished outright. Indeed, celebrated professors of Chinese are calling for still more characters to be added to the humongous total (at least 100,000) that already exist (e.g., see here).

There were about 5,000 different characters on the oracle bones, the first stage of Chinese writing roughly 3,300 years ago, but only around 1,200 of them have been identified with any degree of confidence.

The first major dictionary of individual characters, Shuōwén jiězì 說文解字 (lit., "discussing writing and explaining characters" [there are different interpretations of the title]), completed in 100 AD, contained 9,353 glyphs.

The Kāngxī Zìdiǎn 康熙字典 (Compendium of standard characters from the Kangxi period), published in 1716, which was the most authoritative dictionary of Chinese characters from the 18th century through the early 20th century, had 47,035 glyphs.

Putting an enormous burden on users of the script, the number of characters has continued to balloon up till today. The nature of the Chinese writing system has not changed: it is still fundamentally open-ended, with a potentially infinite number of additions that could be made to it. These are verities that I have been bemoaning for the past half century and more. Except for a few comprehending colleagues, it has been pretty much a matter of vox clamantis in deserto.

Consequently, I was much relieved to come across this article by Piers Kelly, Charles Kemp, and James Winters:

The Conversation (December 14, 2022)

…

Over time, letters adapt to become simpler to write and easier to read. Cultural transmission theorists refer to this process as “compression” and it seems to kick in as soon as people start using a script and teaching it to others.

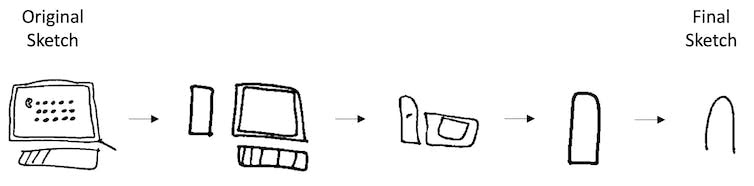

A delightful Pictionary-based experiment shows just how this might unfold in practice. A player who is asked to draw a computer monitor will sketch a detailed picture so the guesser has the best chance of success. But when those same two players are given the exact same clue again and again, the “monitor” might be reduced to a few rectangles and then a simple wavy line. As soon as a simpler convention is established it makes sense to cut corners.

Simplification occurs when players repeatedly sketch ‘Computer Monitor’ in the game of Pictionary. Image derived from Figure 11 of Garrod et al (2007).

But while English readers are only contending with 26 letters, readers of Chinese manage to process over 4,000 core characters, some made up of dozens of strokes.

The sign 麤 (cū, “to be rough with someone”), for example, is evidently much more complex than the alphabetic letter “o”. If Chinese writing is subject to similar pressures, why didn’t this sign simplify?

Our newly published research grapples with this very problem. We found the Chinese script has evolved towards greater visual complexity over the course of its 3,600 year history.

As early as the 1600s, European scholars began to compare archaeological inscriptions across different sites and historical periods.

They noticed signs that started out as pictures tended to become simpler and more abstract over time.

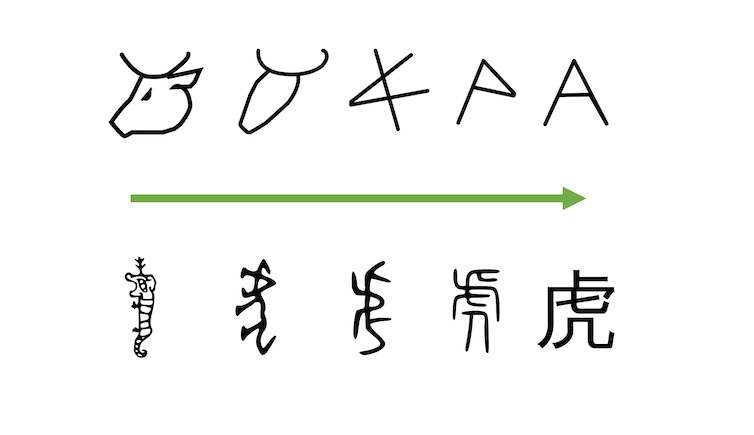

Some of these scholars assumed the Chinese writing system had been trudging along a similar evolutionary path. Just as a hieroglyphic representation of a fish may have simplified into the letter D, and an ox’s head simplified into the letter A, Chinese characters are thought to have condensed from pictures of things to simpler sets of strokes.

The evolution of A and 虎. Piers Kelly

…

Even contemporary sources make the claim that Chinese has been steadily simplifying across its history. But our research suggests the opposite is true: Chinese writing has become increasingly complex.

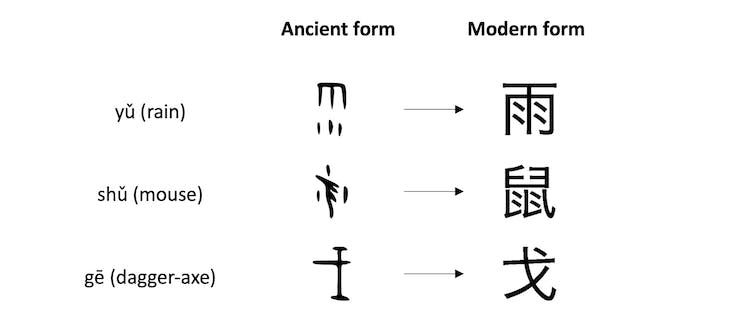

Many Chinese characters have become more complex over time, including the three examples shown here.

…

We wanted to know how intricate Chinese character writing was over time. We used a computational method to trace the perimeters of each letter. The longer the perimeter, the more complex the drawing.

We used this method to measure more than 750,000 images of Chinese characters across five historical phases, from 1600 BC to the present day. The historical trajectories of many of these characters can be visualised here. Far from simplifying or staying the same, on average Chinese characters have become more complex with time.

…

As the set of Chinese characters became larger and larger over the centuries, writers found it necessary to add extra bells and whistles to increase the contrast and tell each character apart. A reader of Chinese text can absorb the words with ease because of innumerable tweaks that keep the system at just the right level of complexity.

…

I often point out to my students how many common characters had their radicals added to them in medieval times, even though the morphosyllabograms originally used to write the words in question over a thousand years before were much simpler, e.g., húxū 鬍鬚 ("beard").

Provocative link from the quoted article

- "If you speak Mandarin, your brain is different" (2/24/15)

Selected reading

- "Writing: from complex symbols to abstract squiggles" (6/11/19)

- "Love those letters" (11/3/18)

- "Pinyin in practice" (10/13/11)

- "How many more Chinese characters are needed?" (10/25/16)

[Thanks to Jim Breen]

Taylor, Philip said,

December 16, 2022 @ 3:55 pm

Totally peripheral to the real theme of this thread, but I could not help but be amused at the speech bubbles that are immediately visible if one follows the link to "If you speak Mandarin, your brain is different".

On the very day that Lady Susan Hussey offered an personal apology to Ngozi Fulani for repeatedly asking the latter where she was from (a question which everyone to whom I have spoken believes was simply a sincere expression of interest), the third question in the right speech bubble reads — wait for it … — "Where are you from ?". As a native speaker of British English, this is a question I have asked many times, wanting to learn more about the person with whom I am speaking. And my wife, who is Vietnamese, is asked almost daily by clients at her hotel where she comes from — she, like I, regards such questions as genuine expressions of interest, and is not in the least offended by them.

Julian said,

December 16, 2022 @ 5:47 pm

From the record it appears that Lady Hussey asked her questions in a pushy, intrusive, repetitive way, refusing to accept the answers, that went far beyond the sort of innocent curiosity that you describe.

The kindest thing you can say is that possibly she is not totally compos mentis and losing judgement about social boundaries. I understand that can be a precursor to dementia.

Victor Mair said,

December 16, 2022 @ 5:50 pm

In the United States, we are sensitized against asking people where they are from. I guess it's because we are a nation of immigrants who have come together in a melting pot. At least it's that way with my family and all of our friends. It's considered bad manners, or worse, to ask people pointblank where they are from. Often, though I'm genuinely interested in learning where someone is from, whether it might be Idaho or Nepal or Russia, I refrain from asking them. Instead, I hope that in the course of our conversation, my interlocutor will volunteer that.

david said,

December 16, 2022 @ 9:26 pm

@VM I sometimes ask people “Where did you go to high school?”

When I started college in a new city, I naively told a night watchman I was from Baltimore. He replied “That’s a good place to be from.” Since then I don’t ask people where they are from.

Christian Horn said,

December 17, 2022 @ 2:06 am

Fascinating, I had never considered the trend could be towards more complex Kanji over time.

It makes perfectly sense though for them to get more complex, while making them easier for the reader to tell them apart. The burden of writing is done just one time, but the reading is done multiple times. Also, the burden of writing more complex Kanji is only felt when writing with pen or brush, but more and more writing is done on a smartphone or a computer. The complexity is then not relevant any more.

wanda from connecticut said,

December 17, 2022 @ 3:58 am

I would wager that Philip Taylor's wife is not bothered by the question, "Where are you from?" because she is in a space (a hotel) where basically everyone is from somewhere else. The question becomes offensive when it highlights that the speaker thinks the person asked must be from "somewhere else"; it highlights their "otherness." And it *really* hurts when the person asked really is from "here," because the question implies otherwise. This happens a lot with second-generation Asian people in the US. I've witnessed multiple conversations that go something like this: "Where are you from?" "Connecticut." "No, before that?" "No, I grew up in Connecticut." "No, where are you really from?" and the questioner wouldn't stop until they got the name of some country in Asia. This is offensive because not only is the questioner implying that the other person is a foreigner, they are also insisting the other person is a liar who is not really from where they said they were from! If that is what happened with Lady Hussey and Ngozi Fulani, I can completely understand why it would bother Ms. Fulani so much.

Taylor, Philip said,

December 17, 2022 @ 5:07 am

Worth noting, perhaps, that in lesson two of Kan Qian's Colloquial Chinese, Fāng Chūn (a young Chinese man) asks Amy (a young American, though he does not know that at the time) 你是哪国人? (Nǐ shì nǎ ɡuó rén ?/ Which country do you come from ?). After a little verbal sparring, Amy concedes that she is an American and asks Fāng Chūn in turn 你是哪裡人小方 (Nǐ shì nǎlǐ rén, Xiǎo Fāng / Whereabouts do you come from ?)

T'ung and Pollard's earlier work with the same title has the interlocutor ask 他們是哪國華僑 (Tāmen shì něi guó huáqiáo / Which country are they from ?), also in chapter two.

Philip Anderson said,

December 17, 2022 @ 6:04 am

I think it’s normal for a language’s vocabulary to increase over time, with borrowings and inventions. With a phonemic script, be it an alphabet, abjad or syllabary, it’s pretty easy to write a new word (even if different spellings compete), but it seems that the Chinese are more likely to create a new character by modifying an existing one? And if a character is simplified, both forms exist?

London being multicultural, people can be sensitive too, but it’s not rude to ask where someone is from; not accepting the answer or asking where they are really from, that is unacceptable.

Mark S. said,

December 17, 2022 @ 10:36 am

@Philip Anderson

I'm glad you brought things back on topic with your question about whether both forms exist if a character is simplified. That's something I'd been wanting to mention.

The answer, of course, is yes, especially if we're referring to decades or even centuries rather than millennia. One of the effects of so-called character simplification is that since the 1950s relatively educated people in China and some other places need to learn even more characters than before, as they must still learn traditional forms on top of the "simplified" versions. Sometimes that's no big deal, as in the standardized left-size element in 話 and 话. And sometimes it was a good idea, such as in dropping particularly complex forms in favor of ones that had already existed in common use for a long while (e.g., 臺 and 台; even plenty of Taiwanese can't write the strokier version without help). But in many other cases, the transformation is trickier and thus more difficult to remember.

For the most part, the character "simplification" in the 1950s PRC was a waste of time and effort, and something that was ultimately used as an excuse to put off what would have been a much more important and effective reform: romanization.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 17, 2022 @ 12:50 pm

Interesting paper. Yeah with Chinese one looks at modern transcriptions of 2000-year old inscriptions and thinks 'Martian gobbledygook' then looks at the original and feels 'ah thanks for the dumb version' — so this result makes complete sense.

Jerry Packard said,

December 17, 2022 @ 2:35 pm

Of course characters increased in complexity from the oracle to the bronze to the seal characters. But they decreased in complexity from the seal characters to the traditional (繁体字) set and from the traditional to the simplified (简体字) set, as the authors clearly demonstrate.

As the authors state in their original research study, "… as expected our results for both handwritten and printed characters confirm that simplified forms are less complex than traditional forms…". So, putting scare quotes around the words "simplified" and "simplification" when referring to the present-day simplified character set is disingenuous.

Jerry Packard said,

December 17, 2022 @ 3:49 pm

And, of course, the character 麤 (cū, “rough, crude") is no longer used — the character 粗, with many fewer strokes, is used in its place. So they should've picked a better example for the point they were trying to make.

Jonathan Smith said,

December 17, 2022 @ 5:41 pm

To be clear, the paper (see esp. Fig. 2) shows a "complexity" peak at Seal Script — this doesn't affect the point that modern forms (both simplified and traditional) appear to be more "complex" than early inscriptions on bone/bronze (and certainly also than early bamboo/wood brush writing, though such forms aren't considered.)

And if we turn to current font faces as opposed to handwriting, note the peaks are instead in the modern period…

Although questions could be raised re: the assessment of "complexity" such that this is the above is case (that is, it may not be interesting that digitized character forms have smaller areas relative to perimeters ratios and thus emerge as more "complex" than handwritten forms by the authors' methodology.)

Chris Button said,

December 18, 2022 @ 7:42 am

I have only read the o.p. here rather than the paper itself, but at first glance this seems to be missing the fundamental point that the script has simplified and regularized around a set of 30-odd strokes, which could in a sense be compared to the letters (i.e. strokes) of an alphabet. There is no such regularity (i.e. simplicity) in the earliest inscriptions.