Womanless

« previous post | next post »

Photograph of a work of art in a Berlin gallery, taken by Johan Elverskog:

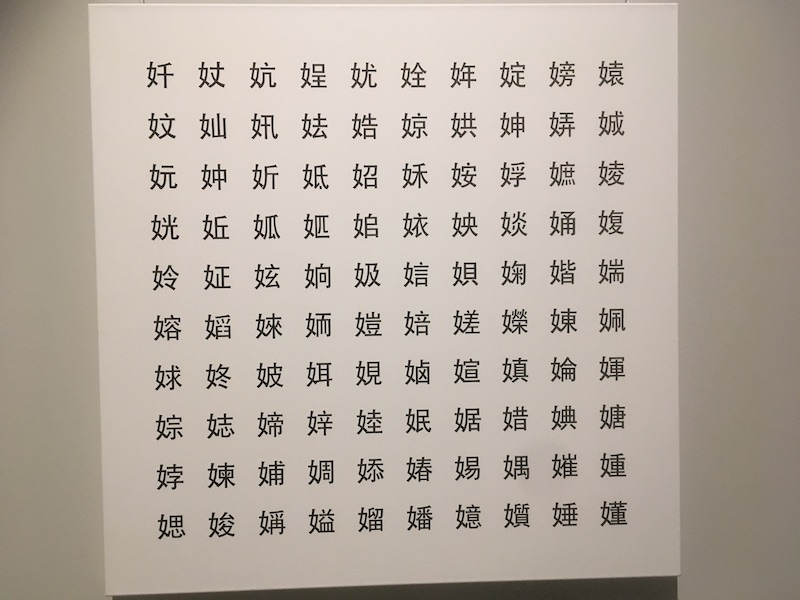

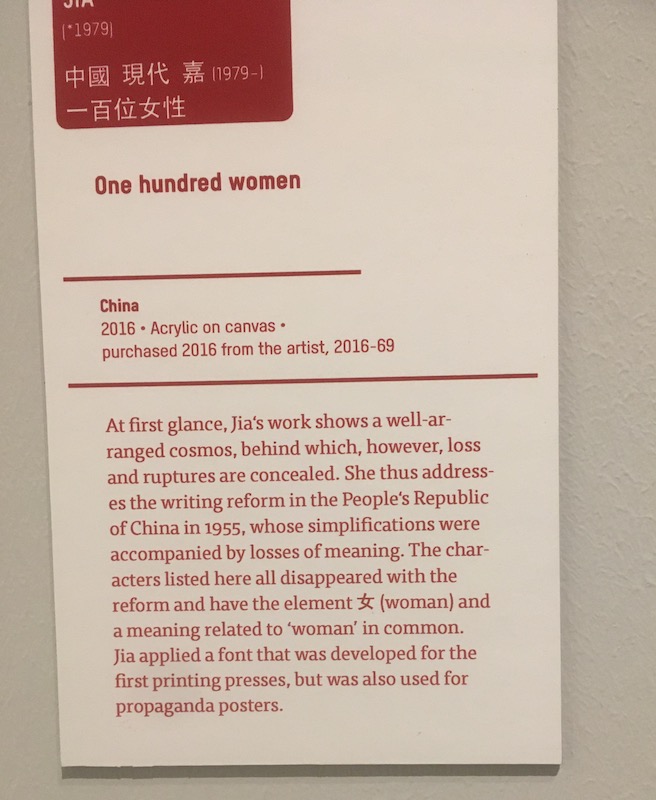

Jia. One Hundred Women, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 78 3/4 inches

Based on her gallerist in Santa Monica, Jia 嘉 is the artist's nom de plume.

The label reproduced above explains fairly well what has happened. I invite Sinographically literate Language Log readers to tell us how a few of these no longer existing characters were pronounced and what they meant. Except, wait a moment! No script reform movement can obliterate a character. Once a character has been created, it exists for all time.

Selected readings

- "Misogyny as reflected in Chinese characters" (12/25/15)

- "Women's words" (2/2/16)

- "This Little Red Book Confronts Sexism in the Chinese Language: By adapting the female radical (女) in 30 compound Chinese characters, designers have developed a new vernacular of feminist-leaning words and phrases", by Liz Stinson, Wired (2/1/16)

- "Women's writing: dead or alive" (10/2/20)

- "Scripts in Google International Women's Day doodle" (3/9/19)

- "All-purpose word for 'glamorous woman'" (10/16/21)

cliff arroyo said,

November 11, 2021 @ 9:45 am

So….. Jia's point is that the Chinese writing system is too _simple_?

Mkay…..

Scott P. said,

November 11, 2021 @ 10:10 am

That is clearly not her point.

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2021 @ 1:17 pm

To get the ball rolling, top left character:

qiān 奷 ("ancient woman's personal name")

bottom right:

dǒng 嬞 ("ancient woman's personal name")

That should give you a hint of what's going on here.

Thomas said,

November 11, 2021 @ 2:19 pm

As a learner of Chinese, this looks to me just like a compilation of characters that exist just to spite me. I guess in most cases, the woman radical does not change the pronunciation and thus just serves as an embellishment. Whenever this is not the case, I can understand too well why these characters were "reformed" away.

Rosie Redfield said,

November 11, 2021 @ 2:37 pm

One issue is whether the 'non-woman' version of the character would have been usually read as implying a man, or a person of unspecified gender.

cliff arroyo said,

November 11, 2021 @ 4:26 pm

"hint of what's going on here"

Are they mostly/all names?

"a compilation of characters that exist just to spite me"

That has been my unchanging evaluation of characters (they existed to make life needlessly difficult) ever since giving up on Japanese many, many years ago. Life is too short (and learning them meant I wasn't learning things that interested me more).

"the 'non-woman' version of the character would have been usually read as implying a man, or a person of unspecified gender"

If they're like female ta then…. by all means junk them as they serve no useful purpose.

Philip Taylor said,

November 11, 2021 @ 4:54 pm

How to parse "ancient woman's personal name" ? Is it (ancient) (woman's personal name) or (ancient woman's) (personal name) ?

John Swindle said,

November 11, 2021 @ 8:39 pm

If by "'non-woman' version" you mean just removing the "woman" radical from each character, the resulting characters wouldn't refer to persons at all. For example, fourth row from bottom, left to right, "seek winter skin ear see salt proclaim real ?contemplate army."

I'm guessing that the idea is that the character sounds or sounded like the right-hand part but means something about woman, here (usually? always?) a name for a woman.

In what sense have these characters disappeared with reform? Were they on an early draft list of characters to abolish? Simplified to something unrecognizable? Omitted from modern compendia? Or what?

Could you swap something male for "woman" and make men's names, or are only women's names marked?

VVOV said,

November 12, 2021 @ 6:17 pm

The title, "One Hundred Women" (女性), surely indicates it's deliberate that most of the characters in the piece are female personal names. The English object caption seems to miss the point in describing the characters as having "a meaning related to 'woman'".

Phil H said,

November 12, 2021 @ 11:09 pm

婖 (near the middle, second row from the bottom), also a female name, modern pronunciation tian 1st tone.

Talking about modern pronunciations seems particularly useless for these characters that aren’t even in use any more! Pulleryblank suggests that the reading in Middle Chinese would have been “tem” with a rising tone, but who knows if that’s the right era to be thinking about?

Diana S. Zhang said,

November 14, 2021 @ 11:52 pm

Has anyone tried to do a statistical finding on whether these "disappeared" words with "woman" element are hapax-legomena before the founding of PRC or writing reform? If they are (or perhaps, to my instinct, all are), then why singling them out from the "disappearance" of countless hapax-legomena throughout the history of Chinese writing and literature? Many a character that has been only found in the Grand Fu genre of the Western Han (ca. 2nd century BCE) were abandoned in usage ever since, and could not be recognized anymore when the time came to the Tang Dynasty (ca. 7th century CE). Ditto for the inability to recognize Oracle Bones Inscriptions after the standardization of "Chinese orthography" since the Qin Dynasty (220 BCE). Then what would be the difference for a modern person not having knowledge in any of these 100 "woman" characters used in Classical Chinese?

This is so politically driven that I'm deeply uncomfortable with it. And I believe that an animal protection activist can find 100 such characters with "犭" (an element usually used for animals, such as 狗 "dogs", 猫 "cats", etc) that are historically discontinued. An environmentalist would find 100 such characters with "木" that represents trees. Anyways, I see this feminist artist's point, but I am quite repelled by the way that she's trying to make it that does injustice to many subjects on many levels.

John Swindle said,

November 17, 2021 @ 5:39 am

@Diana S. Zhang: Your questions have answered mine. Thank you.

Movenon said,

November 18, 2021 @ 11:10 pm

姩 (1st row, no. 7) has regional usage in Cantonese as well as quite a few other regional lects.

http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/dictionary/characters/1721/

https://baike.baidu.hk/item/%E5%A7%A9/3854755