The role of long-distance communication in human history

If one has a knee-jerk reaction to attribute all distant cultural resemblances to chance coincidence (independent invention), that would be to make a mockery of human mobility and adaptability. It would be as if people never deigned or had the opportunity to borrow something from another group.

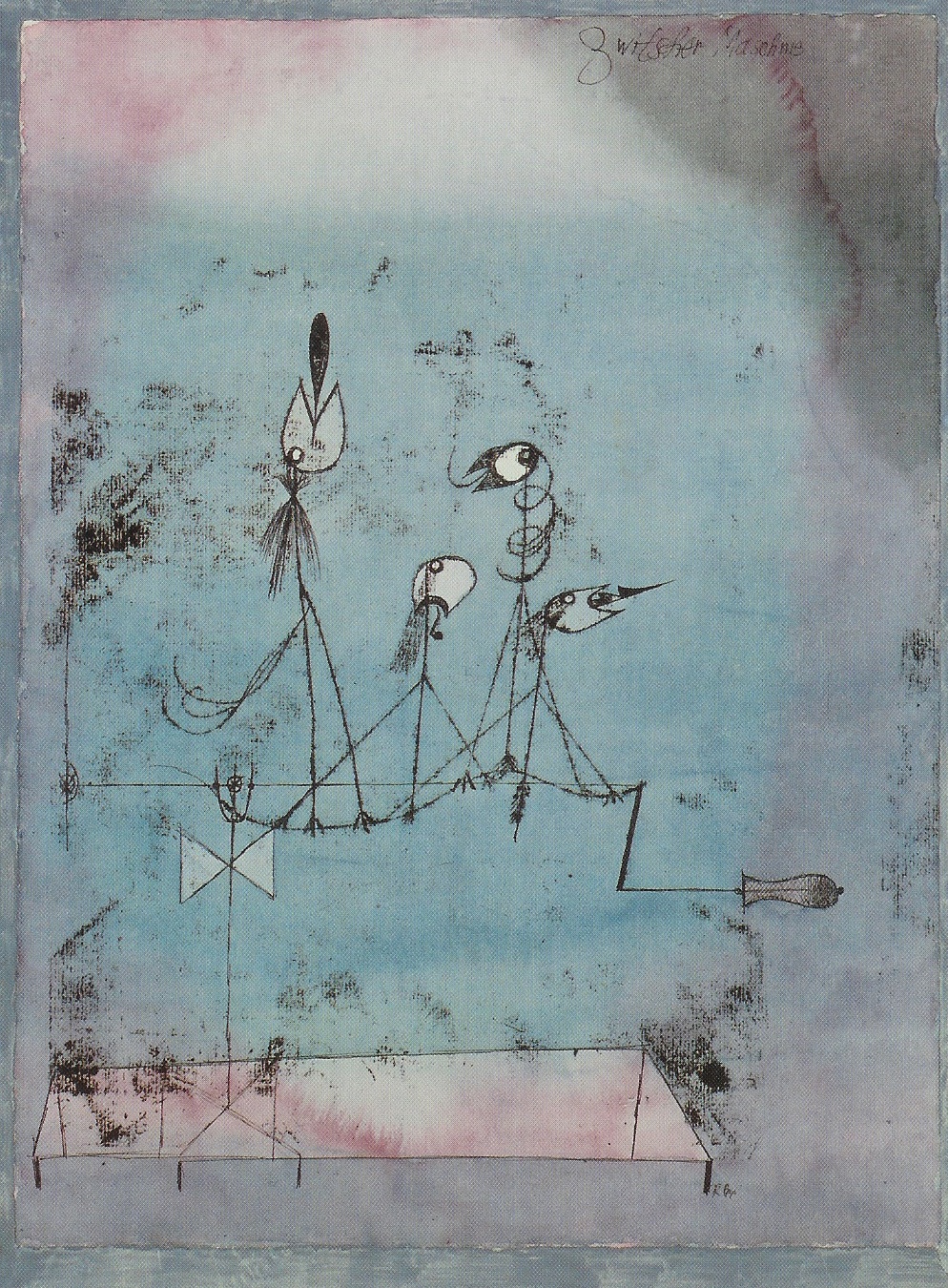

I can give hundreds of long distance cultural correspondences that could not possibly have been due to chance coincidence — so complicated, intricate, and exact are they, especially when accompanied by textual, artistic, and other types of evidence, much of it hard / material. Moreover, we often have the bodies and the goods and the words — at transitional stages and times — to go along with the transmission. For some examples, see the "Selected readings" below. Many more could be adduced.

Read the rest of this entry »