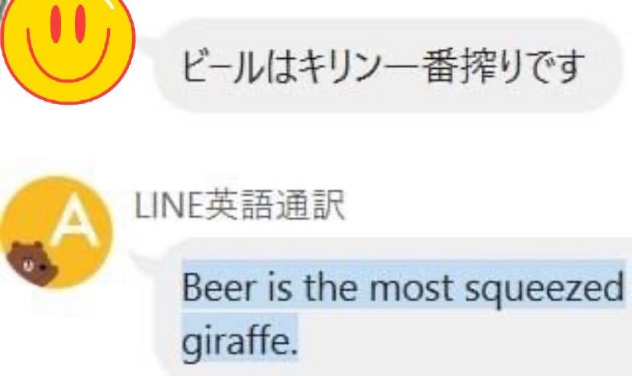

A former geisha becomes Kimono Mom and learns English

The following note and video were sent to me by Bill Benzon. The video is too long (19:15) to make as the main content of this post, but it is captivating, and I warmly recommend it to anyone who is interested in the topics it covers, especially English language learning by Japanese.

The video features Moe, the former geisha who successfully transitioned to Kimono Mom. Among her interlocutors is a woman from Brazil who has a lot of interesting things to say about Portuguese (especially how different the grammar is from English). Aside from discoursing on language teaching and learning, Moe is very good at talking about food and cooking for her little family, so if you like that sort of thing, hop on her channel (see below) and you will have many popular videos to choose from.

Read the rest of this entry »