"Beer is the most squeezed giraffe"

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Nathan Hopson]

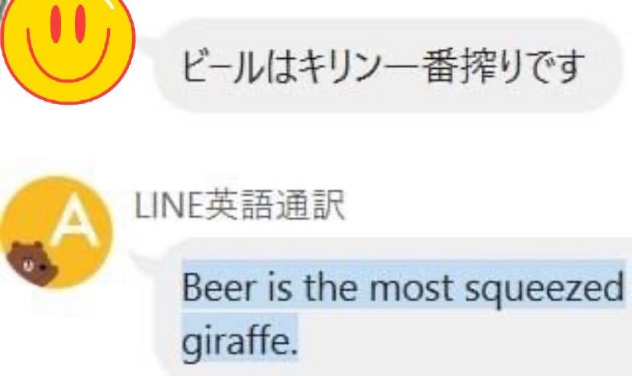

Today I bring you this cringey translation from the social networking app Line (developed in South Korea, very popular in Japan):

ビールはキリン一番搾りです。

Beer is the most squeezed giraffe.

Biiru wa Kirin ichiban shibori desu.

To be fair, there are at least three problems here, two of vocabulary and one of grammar:

1. Kirin (キリン) is the proper name for one of Japan's largest beverage companies, but is also the word for both a mythical creature (麒麟) and, by way of malapropism, for the giraffe.

2. 一番搾り is not "most squeezed," but instead "first squeezed," i.e., first pressed. In fact, this beer is marketed abroad as First Press. The company explains:

First Press describes the craft of extracting only the first press of liquid from the malt, when ingredients are at their purest, much like extra virgin olive oil. Most brewers use a blend of first and second pressed malt liquid, however KIRIN is the only beer in the world to use the First Press method.

In other words, the claim is that this beer is made with only the first runnings. We can safely assume that there are cheaper beers produced by sparging the same malt.

3. The particle は. It is usually described as the "topic marker," but there's often precious little explanation of what that means in practice. My suggestion is to at least initially consider は and its antecedent as an entirely separate sentence that merely introduces the topic (hence, topic marker). In this case, "Let's talk about beer." That topic then becomes the invisible, assumed subject of the next sentence, best represented in English by "it."

The result is:

Let's talk about beer. It's Kirin First Press.

Alternatively, we could see ビールは as "When the topic is beer…" In other words:

When the topic is beer, [something] is Kirin First Press.

More colloquially:

When it comes to beer, it's Kirin First Press.

This might not completely solve the problem of excessive giraffe squeezing, since that's more a matter of semantics than of syntax (or pragmatics, I suppose, if you're the giraffe), but it would at least point a human translator in the right direction.

Selected readings

- "Of reindeer and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/23/18) — includes extensive, detailed discussion of xièzhì 獬豸 ("goat of justice"); 麒麟 / 騏驎

- "Reindeer talk" (12/24/13)

- "Reindeer lore " (12/8/16) — includes 95 comments with words for reindeer in different languages, plus descriptions of customs and culture concerning reindeer

- "'Mulan' is a masculine, non-Sinitic name" (7/15/19)

PeterL said,

July 17, 2022 @ 11:27 pm

A few days ago, I tried "ビールは麒麟一番搾りです" on Google Translate and got "Beer is the most squeezed Kirin" (I don't recall if キリン got "giraffe" or "Kirin"). But today it gives "Beer is Kirin Ichiban Shibori" for both キリン and 麒麟. I wonder what Line is doing today …

This is a variant of a well-known Japanese mis-translation "僕はうなぎす" (boku wa unagi desu) as "I am an eel" but should be "For me, it's eel" (when ordering at a restaurant) or "I'll have eel". My amateur Japanese analysis is that "desu" is just an obligatory copula (the minimal Japanese sentence has either a verb or copula, although it is sometimes left out in colloquial speech) and "wa" is a topic marker. Here is one explanation of "wa": https://www.imabi.net/theparticlewai.htm

Toby Blyth said,

July 17, 2022 @ 11:49 pm

My heuristic is when in doubt, translate "was" as "as for".

Dan Milton said,

July 18, 2022 @ 11:41 am

"cheaper beers produced by sparging the same malt"

It appears you know some technical term in brewing, but I don't see anything under "sparge" in the OED that fits. What have we missed?

Stephen Hart said,

July 18, 2022 @ 12:02 pm

The standard Mac dictionary lookup yields:

sparge | spärj | mainly technical verb [with

object]

moisten by sprinkling with water, especially in

brewing: the grains are sparged.

Elizabeth said,

July 18, 2022 @ 7:31 pm

Computational linguistics thought: this is a named-entity recognition (NER) failure.

Japanese thought: I'm not a native speaker, but the first reading I had was: "My favorite beer is Kirin Ichiban Shibori".

But it could also be: "The beer we're having (at the party) is…" or "The beer they serve (at the restaurant is…" or…

Paul McCann said,

July 19, 2022 @ 12:20 am

Line has actually always been developed in Japan, though the parent company of the Japanese company that develops it is Korean. They also used Korean servers at some point, though that stopped after it caused controversy.

Terry Hunt said,

July 19, 2022 @ 2:50 am

@ Dan Milton – OK, I'll have to get a bit beer-nerdy here.

Beer starts with cereal grain, most often barley, but others can be mixed in or substituted. The grain is moistened, spread on a heated malt house floor and regularly turned with a malt shovel until it begins to sprout. This means that the starches stored in the grain have mostly turned to sugars.

The sprouted grain is then kilned (lightly roasted) to kill it and add further flavours and colour – the longer/hotter it's kilned, the darker it (and the eventual beer) becomes and the more smokey/chocolatey it will taste. It's now called malt. Many beers are made with a mix of two or more different malts to exploit their different characteristics.

The malt goes to the brewery, which lightly grinds it in a grist case to crack/loosen the husks, then pours it into a round mash tun mixed with a stream of hot water (in brewspeak, water is called liquor), resulting in sloppy porridge called mash.

This mash is simmered for an hour or three to dissolve the sugars, plus proteins and other constituents, into the water. Naturally this steams off some of the water, but it's essential that the mash doesn't get too dry and that its volume is maintained, so – and finally we get to your query –

More water is, fairly continuously, sprinkled on to the top of the mash, so that it percolates down, dissolving more sugars, etc., and maintaining the volume and consistency of the malt. This process is called sparging! It's a sensitive operation, too little and the simmering mash collapses, blocking the grid or mesh at the bottom of the tun through which the liquid product (called wort) will be drained, too much and the mash will over-cool, weakening the wort and throwing off the volume calculations essential to later parts of the process.

The wort is then transferred to the copper (literally a giant kettle) with more liquor and boiled for an hour or three, with ingredients such as hops (usually atleast two different varieties, for flavour and aroma) and trace minerals (to feed the yeast and further modify the flavour/aroma) added. Thereafter it's passed via wort receivers, through coolers, and into open-topped tanks called fermenting vessels, where the yeast (often a strain evolved in and unique to the brewery) is added and does its thing for several days, converting the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, both of which dissolve into the wort, resulting in beer. Once most of the sugars are used up, leaving a small amount depending on the beer's desired sweetness, it's transferred to settling vessels where most (but not all) of the yeast drops to the bottom, and/or maturation tanks (in which the flavour continues to develop) before being bottled or casked (in which containers the remaining, or some newly added, live yeast continues to perform).

(Do not utter the word "keg" in the presence of real ale enthusiasts, unless you ritually spit beforehand. Kegs are used for beer that is filtered to remove living yeast; pasturised – altering the flavour and driving out the naturally dissolved carbon dioxide; and re-carbonated with industrially produced carbon dioxide to excess pressure – used in the serving process; resulting in a bland, dead, unmaturing, over-fizzy product. But I digress.)

Historically, two or three rounds of sparging were perfomed on the contents of the mash tun. The first-produced wort would result in the strongest, fullest-bodied and tastiest beer, the second in a weaker beer (equivalent to a modern "session beer"), and the third in a weak (1–2% ABV) "table beer" that everybody, including children, drank because it was much healthier than most water supplies. (As well as being tasty, somewhat nutritious, and mildly inebriating – what's not to like?)

My edition of the OED (1971) has generous entries on Sparge as a verb (to sprinkle), and noun, the act of sprinkling or that which is sprinkled), mostly in brewing but also in other contexts.

[For transparency, I've personally performed all of the brewery operations mentioned above (plus others, like cleaning), as well as delivering, cellaring, tapping and serving beer. I've done my share of drinking it, too.]

Terry Hunt said,

July 19, 2022 @ 2:52 am

Sorry for the italic screw-up above. Oh! for a preview function.

F said,

July 19, 2022 @ 4:38 am

(Dan Milton)

OED def 4a: "Brewing. To sprinkle (malt) with hot water."

Elizabeth said,

July 19, 2022 @ 5:30 pm

Update: my husband (a native speaker) says that "My favorite beer is Kirin Ichiban Shibori" is the reading that most readily comes to mind. He also mentioned one I hadn't thought of, "The quintessential beer is Kirin Ichiban Shibori".

In any case, either a human or a machine translator would require further context to produce a good translation for this sentence.

ohwilleke said,

July 20, 2022 @ 7:13 pm

Another translation snafu tip: https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2022/07/china-new-product-fact-of-the-day.html

~flow said,

July 22, 2022 @ 10:04 am

I'm getting the feeling that the intended meaning is close to sth like "when beer, then Kirin" with a hint of "beer, thy name is Kirin" and a subtle note of "best beer—Kirin only" although the latter is well out of the literal-translation realm of ビールはキリン一番搾りです。(一番 is both 'first' and 'foremost', so to speak)

Stephen said,

July 23, 2022 @ 6:34 am

@Terry Hunt

"Do not utter the word "keg" in the presence of real ale enthusiasts …"

One linguistic point and one beer one, somewhat related .

1. IME (UK), the term 'real ale' has mostly been replaced by 'cask ale'.

2. There are kegs and kegs. The sort that you are talking about are nowadays often referred to as Sankey kegs, after the type of connector that is used.

This is to distinguish them from key kegs

https://www.keykeg.com/products/

where the beer is inside a bladder (grey in those pictures) inside a rigid plastic housing.

The gas that is used to force the beer out goes in between the housing and the bladder, so it never come in contact with the beer.

The beer inside the bladder can be filtered, pasteurised, etc but it does not have to be and normally is not.

Terry Hunt said,

July 24, 2022 @ 7:19 am

@ Stephen — Yes, there are variations and new innovations with which I didn't want to complicate my basic explanation. Were you involved in the "cask breather" controversy?

Re "cask ale": "real ale" and "cask ale" aren't synonyms; they refer to slightly different things, and the latter term has become more common because the type of ale it refers to has taken over some of the market for real ale, and rather more (I believe) from kegged beers. Pubs tend to advertise themselves as providing cask ales because it gives them more latitude. (Real ales require a little more cellarmanship and serving experience than cask ales, while keg beers are easiest to handle, so the availability of skilled staff can become an issue.)

Without going into minutiae, the "rules" governing what defines a "real ale" are somewhat looser for "cask ales", so while all real ales pass the qualifications for being cask ales, most cask ales are not, strictly speaking, real ales. Diehard members of CAMRA (the Campaign for Real Ale, formed in 1972, which led the movement to prevent a complete takeover by kegged beer), still eschew cask ales. (I'm not that purist.)