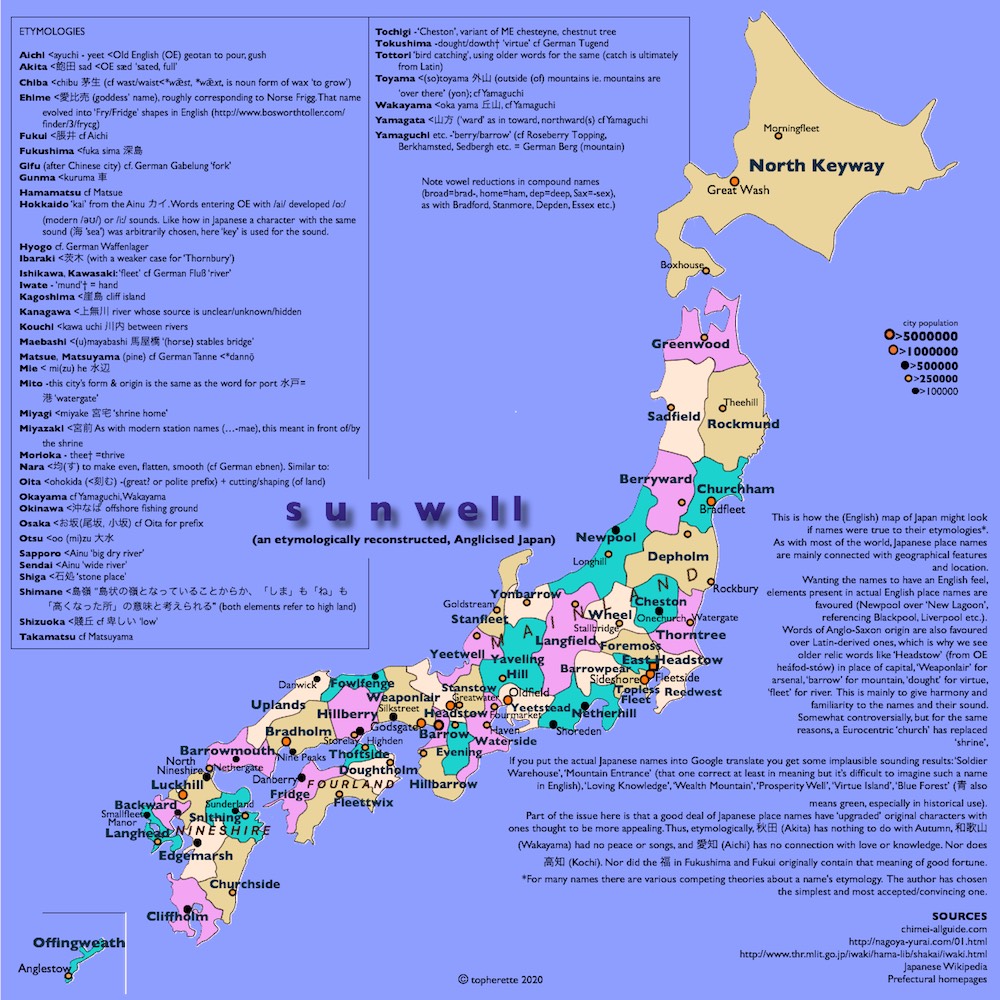

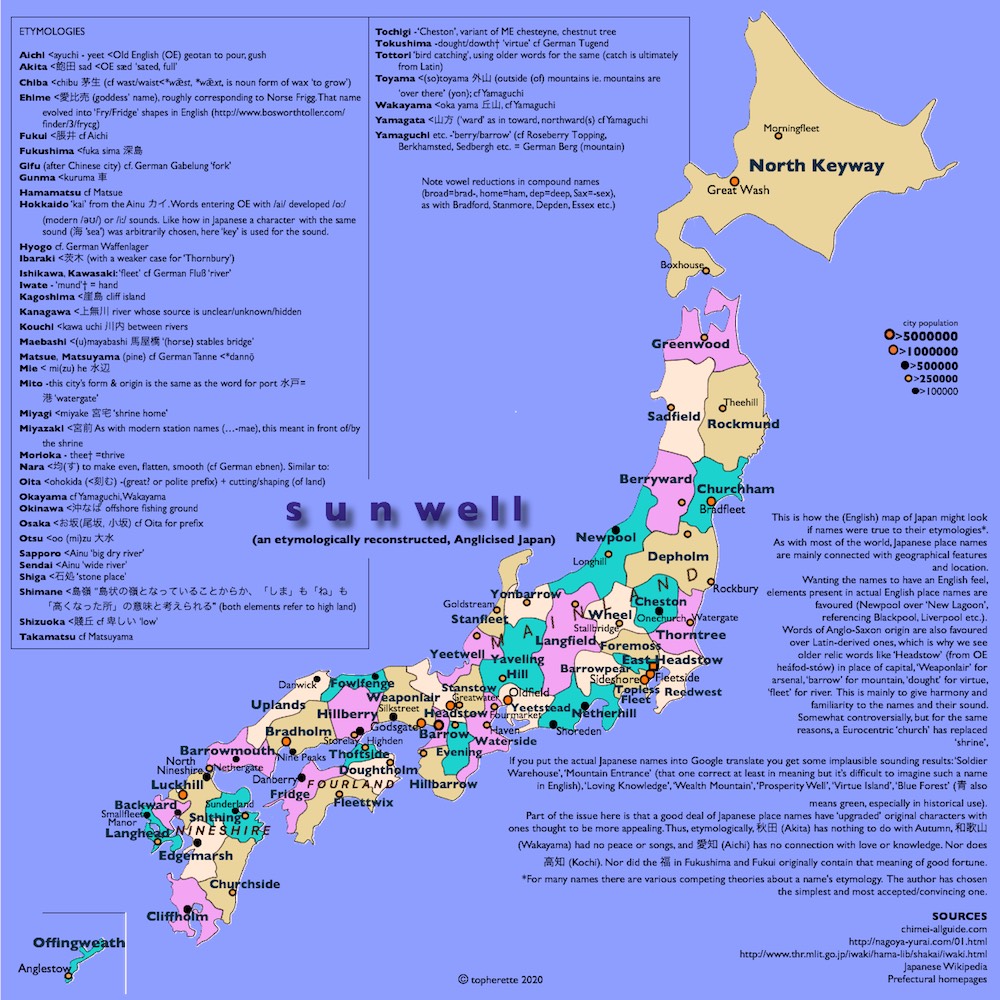

Japanese toponyms Englished

There's a Reddit page with this title: "Fully anglicised Japan, based off actual etymologies, rendered into plausible English". Feast your eyes:

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »

There's a Reddit page with this title: "Fully anglicised Japan, based off actual etymologies, rendered into plausible English". Feast your eyes:

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »

The title and the following observations come from Rebecca Hamilton:

I was reading Patrick Leigh Fermor's Between the Woods and the Water: on Foot to Constantinople, as I convalesce from COVID-19 (I've had a hard time of it), and I stumbled upon an aside he made about the French "hongre," meaning "gelding," as does the German "wallach." He made this comment – without further explication – in the context of a discussion of the ethnographic roots of Hungarians, Wallachians, and Rumanians (in particular, the latter as being descendants of Roman occupation, if not Romans themselves). What all this means, I cannot say. It seemed like a topic you would know something about. Because I am confined to bed for the moment, if you could be so kind as to forward me some reading material, I would be very grateful. Also, anything about "Wales" or "Welsh" sharing etymological roots with "Wallach," and how "wether" fits into all this would be great.

Read the rest of this entry »

In reacting to the fierce denunciation of Xi Jinping by Cai Xia (see bibliographical note at the bottom of this post), Conal Boyce mused:

Mind-boggling material. I had to do a double-take on the passage you show that contains both chǔn and jiāhuo (蠢家伙 ["stupid guy / fellow"]). And sure enough, in the video, she actually uses the term zhèngzhì jiāngshī (政治僵尸 ["political zombies"]) more than once!

These are shocking terms, with a peculiar color all their own. They reminded me that, in a sense, there are no words that are actually 'equivalents' between two languages. For instance, the Turkish for 'cat' is 'kedi', which has a comfortable look of familiarity at first, because of English 'kitty', yet we suspect that the semantic range of 'kedi' in Turkish versus the semantic ranges for 'cat' and 'kitty' in English probably overlap in some unexpected Venn diagram style, with much of 'kedi' not immediately accessible to a speaker of English.

Read the rest of this entry »

The actress Qin Lan, who is best known for her role in the wildly popular TV drama "Story of Yanxi Palace", said this in an interview:

“People have been asking me why I’m not getting married, and some have even suggested it’s ‘irresponsible’ if I don’t have a baby. I think it’s strange.

“What’s it to you if I use my uterus or not?”

That line went viral, garnering its own hashtag on Weibo (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter).

Read the rest of this entry »

From the time I started learning Chinese more than half a century ago, I had a hard time lining up the many Chinese terms for different types of citrus with the corresponding words in English. For example, I always wanted to call oranges "júzi 橘子", but it is technically (botanically) more correct to call them "chéngzi 橙子". As for what júzi 橘子 should be called in English, they are, well, "mandarins" or "mandarin oranges". Ahem! As L said in this comment several years ago, "…in NZ, any small, peelable orange is a mandarin! And would never be considered an orange." (From "Really?!" [12/27/16]).

Then there are tangerines, clementines (cuties), and satsumas, just among closely related varieties of citrus fruits, and I won't begin to get into grapefruit, pomelo, yuzu, citron, bergamot, kumquat, tangelo, kabosu, orangelo, hyuganatsu, rangpur, sudachi, kawachi bankan, etc., etc., and dozens of other types. My old friend, the late Elling Eide (1935-2012), a specialist on Li Bo (701-762) had a grove on his estate in Sarasota, Florida where he cultivated about fifty different types of citrus fruits. What a joy it was to walk through the grove and sample tree-ripened mandarins, tangerines, clementines, grapefruits, pomelos, and all manner of other citrus to satiety!

Be it should be noted that Elling could have all that richness of citrus because Sarasota has a humid subtropical climate bordering a tropical savanna climate, with an average of only one frost per year and rarely drops below freezing (which nonetheless always concerned Elling greatly).

But now we must turn to the main thrust of this post, which is a discussion of the etymology of gān 柑, another name for mandarin(e) (orange), often appearing in the disyllabic form gānjú 柑桔, which includes several closely related subspecies.

Read the rest of this entry »

Boogaloo is in the news these days, in reference to what a recent Forbes article calls "a loose group of far-right individuals who are pro-gun, anti-government, and believe that another civil war in America is imminent". The politics is complex and evolving, as a USA Today article explains:

[T]here are various facets to the loosely organized group: One generally stems from its original ties to neo-Nazis and white supremacists, while a newer facet is libertarian.

"There's a lot of overlap and the boundary is blurry because they both evolved together," said Alex Newhouse, digital research lead at Middlebury Institute's Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism. "It is very difficult to know if the 'boogaloo boi' you see standing in the middle of the street at a protest is there in solidarity or to incite violence."

For further details, see the Wikipedia entry for "Boogaloo movement". The term's linguistic history poses the puzzle of how the name of a Latinx and Black dance fashion came to be adopted by white supremacists:

Read the rest of this entry »

From David Brophy:

I’ve often wondered why the Uyghur word for carrot is sewze, etc., which comes from P. sabz “green”. I know carrots range from orange to yellow, and maybe occasionally purple, but I’m pretty sure there’ve never been green carrots.

It's a good question.

One thing I do know is that, whenever I go to an Indian restaurant, I find sabzi, also spelled sabji, as a vegetable cooked in gravy

I think maybe the word originally just meant "veggies" in Persian, and then developed the specialized meaning of "carrot" in Turkic and other languages.

Ghormeh Sabzi (Persian: قورمه سبزی) (also spelled as Qormeh Sabzi) is an Iranian herb stew. It is a very popular dish in Iran.

——

Ghormeh is derived from Turkic kavurmak and means "braised," while sabzi is the Persian word for herbs.

Looking at Wikipedia, it does say that carrots are likely originally from Persia where they were probably first cultivated for their leaves (which are green).

Read the rest of this entry »

You've probably read about how k-pop stans pranked the Trump campaign — apparently several hundred thousand of them signed up for tickets to Saturday's Tulsa rally, creating embarrassingly over-optimistic attendance predictions. You may even have seen one of the celebratory tiktok videos:

Read the rest of this entry »

If you're looking for words with lots of consonants and few or seemingly no vowels, try Eastern Europe, especially Czechia.

I have a friend named Stu Cvrk, and I asked him the story of his surname and how to pronounce it. Here's what he told me:

It is Czech. The Czech pronunciation is "tsverk". My grandparents Americanized it a bit to make it easier to say, as we now pronounce it "swerk."

The story of its derivation according to family lore is this:

Read the rest of this entry »

[The following is a guest post by John Mock. I am impressed by how much detailed scholarship (although perhaps not always of great precision and rigor) on such an esoteric matter as that discussed herein already existed in the 18th and 19th centuries.]

John Biddulph in his book Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh (Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1880), p. 24, wrote:

I have been told by a Nepalese gentleman that Thum is a Chinese title, meaning Governor, and that it is used in a reduplicated form Thum Thum, to signify a Governor General. [footnote: It is perhaps a corruption of the word Tung, which appears in many titles. The Chinese Governor of Kashgaria is called Tsung Tung, and the officer who commands the troops is styled Tung-lung.] Its very existence in these countries, where its origin has been completely lost sight of, is curious and must be extremely ancient.

Henry H. Howorth, in his article "The Northern Frontagers of China. Part VIII. The Kirais and Prester John", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 21 no. 2 (1889), pp. 383-5, discussing Tang relations with Uighurs, wrote:

The Chinese emperor at this time was called Tham vu tsum.", and, “During the reign of Tham yi tsum, from 860 to 874….

Read the rest of this entry »

Valerie Hansen has a new book just out:

THE YEAR 1000: When Explorers Connected the World — and Globalization Began. New York: Scribner, 2020.

A NYT review of Hansen's landmark volume is copied below, but let's first look at some interesting language notes concerning the background of the word for "slave" (Chapter 4 is on "European Slaves"; the quotations here are from pp. 85-86).

The demand for slaves [in addition to that for furs] was also high, especially in the two biggest cities in Europe and the Middle East at the time–Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine empire, and Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid caliphate, in present-day Iraq. The residents of Constantinople and Baghdad used their wealth to purchase slaves, almost always people captured in raids on neighboring societies.

Read the rest of this entry »

The May 2020 issue of a scientific journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, shows a rank badge of Qing Dynasty officialdom. There are five bats in this piece of ornate embroidery (can you spot them?):

Artist Unknown. Rank Badge with Leopard, Wave and Sun Motifs, late 18th century. Silk, metallic thread. 10 3/4 in x 11 1/4 in / 27.31 cm x 28.57 cm. Public domain digital image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.; Bequest of William Christian Paul, 1929. Accession no.30.75.1025.

(Source)

Read the rest of this entry »

Jessica Hemming, in consultation with Joseph Eska (personal communication), writes:

In the debate about whether Sinitic ‘mra’ could be a borrowing from an Indo-European language, given that only Celtic and Germanic have horse words in *marko, it may be of use to know that proto-Celtic is now conventionally dated to no earlier than c.1000 BC and proto-Germanic to c.500 BC. These would seem to be too late to be options. Also, the native word for horse in Celtic is *ekwo; nobody is quite sure where *marko came from, although later it became the standard medieval word for horse (especially in the sense of ‘war horse’ or ‘steed’ in Middle Welsh).

Read the rest of this entry »