Japanese toponyms Englished

« previous post | next post »

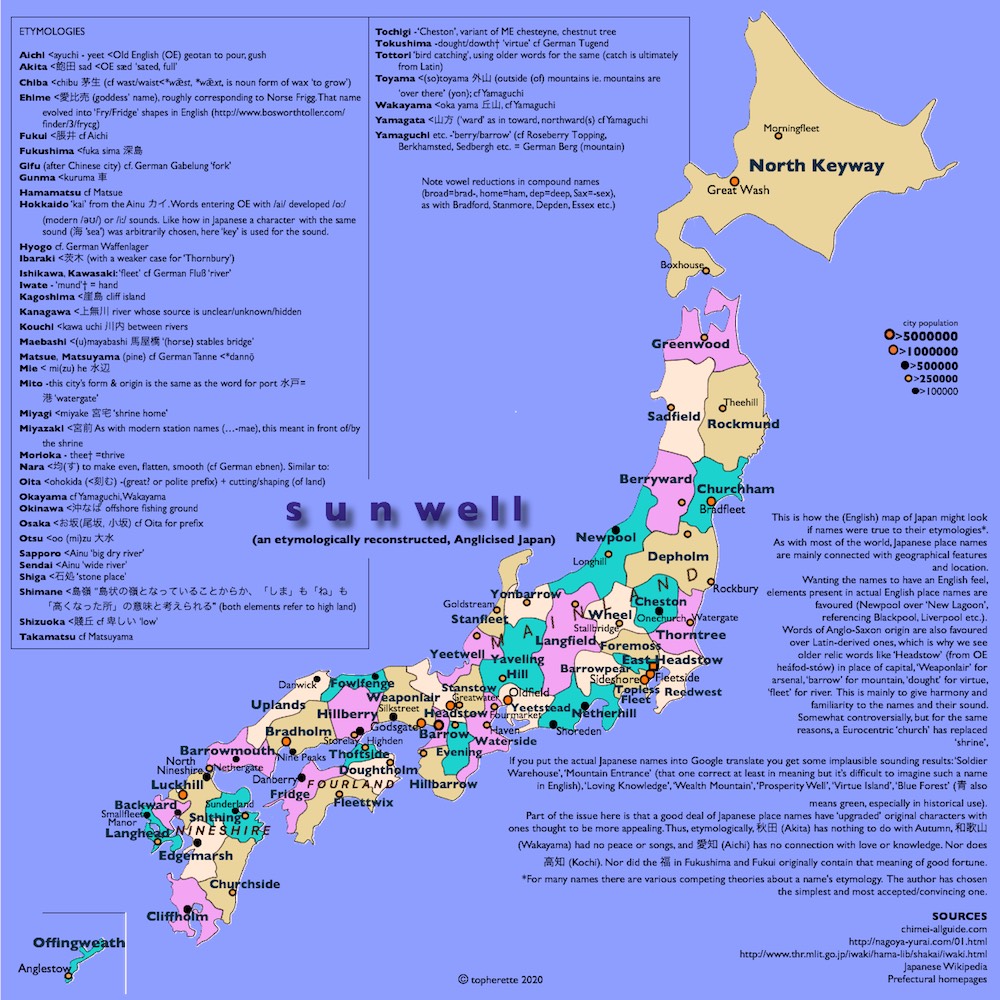

There's a Reddit page with this title: "Fully anglicised Japan, based off actual etymologies, rendered into plausible English". Feast your eyes:

(source)

"Whoa!" I thought. This is amazing! And I took it half seriously because it listed the "etymologies" in the top left quarter of the page, and had what looked like semi-scholarly notes in the bottom right quarter of the page, followed by a modest list of sources below that.

Then I felt behooved to check out a few of the "etymologically reconstructed, Anglicised" Japanese place names. The first one that struck my eyes was in large letters right in the center: "sunwell".

Hmmm! Surely that must be Nippon or Nihon 日本, i.e., "Japan". I have always been told that the name, based on the two characters, means "source / root of the sun". So why does the map call the country "sunwell"? Giving the authors the benefit of the doubt, I decided to look into the derivation of the name "Nippon" or "Nihon 日本" more deeply.

The name for Japan in Japanese is written using the kanji 日本 and pronounced Nippon or Nihon. Before it was adopted in the early 8th century, the country was known in China as Wa (倭) and in Japan by the endonym Yamato. Nippon, the original Sino-Japanese reading of the characters, is favored today for official uses, including on banknotes and postage stamps. Nihon is typically used in everyday speech and reflects shifts in Japanese phonology during the Edo period. The characters 日本 mean "sun origin", in reference to Japan's relatively eastern location. It is the source of the popular Western epithet "Land of the Rising Sun".

The name Japan is based on the Chinese pronunciation and was introduced to European languages through early trade. In the 13th century, Marco Polo recorded the early Mandarin or Wu Chinese pronunciation of the characters 日本國 as Cipangu. The old Malay name for Japan, Japang or Japun, was borrowed from a southern coastal Chinese dialect and encountered by Portuguese traders in Southeast Asia, who brought the word to Europe in the early 16th century. The first version of the name in English appears in a book published in 1577, which spelled the name as Giapan in a translation of a 1565 Portuguese letter.

Whence cometh the "well"? Perhaps there's some deeper, Old Japanese root or reading that escaped me. It was necessary to dig more deeply still.

/nitɨpoɴ/ → /nip̚poɴ/ → /niɸoɴ/ → /nihoɴ/

Coined in Japan of Sinic elements, as compound of 日 (nichi, “sun”) + 本 (hon, “origin”) and literally meaning "origin of the sun". The hon element was apparently pronounced /poɴ/ when first coined. Over time, the initial /p/ lenited, becoming /f/ as shown in the Nifon entry in the 1603 Nippo Jisho ("Japanese-Portuguese Dictionary"). This then became the /h/ sound in modern Japanese.

In older texts, this was read as kun'yomi as 日の本 (Hinomoto). The on'yomi readings Nippon and Nihon became more common in the Heian period, with both persisting into modern use. The Nihon reading appears to be the most common in everyday Japanese usage.

Ah! Perhaps it has something to do with the earlier reading of 本 as moto. That same morpheme, "moto" is also written with the kanji 元 ("origin; source"), which can likewise mean "base; basis; foundation; root".

From Old Japanese. Cited to the Kojiki of 712 CE. From Proto-Japonic *mətə. Cognate with Okinawan 元 (mutu).

Still no "well". Must go one step further. In Old Sinitic, /*ŋon/ 元 is possibly related to / *ŋʷan / 原 ("source; origin; basic; primary"), and the latter is the original form of /*ŋʷan/ 源 ("source of a river or stream; headwaters; headspring; fountainhead; source; origin; root"). Maybe, just maybe, this is where the authors of the map got their "well".

Or maybe the answer is much simpler — they got their "well" from this definition of the English word: "A place where water issues from the earth; a spring or fountain." But to arrive at that, they likely would have gone through some of the steps I described above.

To see whether they were operating at such a philologically profound level, I thought I'd better check a few more of their place name translations.

My gaze wandered northward and I soon spotted "North Keyway". It had to be Hokkaidō 北海道. I can understand how they got "way" for dō 道, but where do they get "key" for kai 海, which means "sea"? Their etymological notes say that "kai" comes from Ainu, but they don't say what it means. Most Japanese understand Hokkaidō 北海道 as meaning "Northern Sea Circuit", where "circuit" is an administrative division of East Asian governments.

Nearby, my eye landed on "Great Wash", and that leapt off the page as being a dramatically creative attempt to render "Sapporo", home of the famous beer.

Sapporo's name was taken from Ainuic "sat poro pet" (サッ・ポロ・ペッ), which can be translated as the "dry, great river", a reference to the Toyohira River.

The etymological notes on the map reveal that the authors dutifully understand that, so their "Great Wash" must be based on understanding English "wash" as conveying the sense of "dry river".

One must be especially careful with place names in Hokkaido, since many of them — though written in seemingly transparent kanji — are based on Ainu substrate terms. Another example: "Otaru", the name of a small city that is not too far to the northwest of Sapporo, is recognized as being of Ainu origin, possibly meaning "River running through the sandy beach". (source)

Otaru 小樽 looks like it means "little barrel / cask / keg".

Sapporo 札幌 looks like it means "banknote; bill; note; paper money; ticket; token; check; receipt; armor platelet" + "canopy (esp. the cloth or canvas used for it); awning; top (of a convertible); hood; helmet cape; cloth covering one's back to protect against arrows during battle".

Similar problems with the kanji readings of place names exist throughout Japan, not just with Ainu substrate terms (see the "Selected Readings" below.

"Sunwell", "North Keyway", and "Great Wash", in that order, were the first three Anglicized toponyms on the Reddit map that I saw, and all three of them are plausible if you put enough effort into understanding how the authors might have arrived at them. Language Log readers who are intrigued by the quaint English names on the map may wish to try their hand at figuring out how the authors devised a few of them. It might make a pleasant way to fill up an afternoon in COVID times, especially when hurricane Isaias is dumping water on you all day long.

Selected readings

- "Japanese readings of Sinographic names" (9/26/18)

- "Sino-Japanese" (7/2/16)

- "An Eighteenth-Century Japanese Language Reformer" (4/23/15)

- "Chinese Japanese" (9/13/15)

- "Two unusual Japanese names" (9/10/15)

- "Amazing things you can do with the Japanese writing system" (7/1/19)

- "Cool slave / guy / tofu / whatever" (5/12/19)

[h.t. Frank Clements]

Ben Zimmer said,

August 4, 2020 @ 12:33 pm

This looks to be modeled on The Atlas of True Names, which I posted about back in 2008. As with that venture, this is amusing enough as long as you're not expecting authoritative etymological scholarship.

Philip Taylor said,

August 4, 2020 @ 1:34 pm

"based off actual etymologies" — "based on", I am very familiar with, but "based off" is entirely new to me. How does "based off" differ from "based on" ?

Lillie Dremeaux said,

August 4, 2020 @ 1:48 pm

I had so much fun comparing this with a map of Japan and reading the notes. Thanks for sharing it.

It seems that the creators prioritized believable English place names over direct translations, which gave the map an amusing cohesion. I thought "Sunwell" jibed well with the literal meaning "source of the sun," figuring that "well" (which can mean "plentiful source," metaphorically … e.g. "she was a well of knowledge") was a much more likely suffix for an English place name than -source or -root. So if the Japanese toponym would be translated literally as "Sunsource," the more plausible version for England would be Sunwell — a gushing source of sun!

With Keyway, I could be misinterpreting, but the note for Hokkaido made it sound as if the "key" sound was chosen arbitrarily to correspond with a similarly arbitrary Japanese sound in the name.

F said,

August 4, 2020 @ 2:05 pm

Now, wouldn't it be more faithful to the spirit of this exercise to render Ainu names in Scottish Gaelic or Welsh, and Sino-Japanese names as Latin/French?

Alexander Browne said,

August 4, 2020 @ 2:17 pm

@ Philip Taylor It's an colloquial American alternative to "based on": base off of (US, informal) To base on. (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/base_off_of#English)

Ellen K. said,

August 4, 2020 @ 2:23 pm

@Phillip Taylor.

I think "based on" and "based off" mean basically just the same thing, just a different metaphor. "Based on": a base that you build on. "Based off": a jumping off spot. And I assume usage does not always follow the metaphor.

Philip Taylor said,

August 4, 2020 @ 3:01 pm

Thank you, Alexander & Ellen. Following your comments I then searched the web for "off of", found diametrically opposed views as to whether "off" or "off of" is more formal, but ended at the following by John Cowan which, of all the contributions I read, seemed to make the greatest sense to me :

Peter Taylor said,

August 4, 2020 @ 4:47 pm

I presume "Fleettwix" to be a fast chocolate bar, but I'm not sure what "Yaveling" means.

The same author has also done a similar map of China and bits of its neighbours.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 4, 2020 @ 5:12 pm

I second Lillie Dremeaux. This is supposed to look like real English place names first and foremost. If the etymology makes some sense, then hooray, but if it doesn't, that wasn't the point of the map.

In a similar vein, what if the London Tube had German station names?

https://youtu.be/pGeza649glo

Kristin said,

August 4, 2020 @ 7:23 pm

Curious about where the etymological break-down came from. For example, Osaka is actually Oosaka or Ōsaka, where the initial long O means big, rather than "tail" or "small" as noted above… I love the idea, but I think the Japanese etymologies may have benefitted from the involvement of a native speaker…?

Twill said,

August 4, 2020 @ 10:06 pm

@Kristin According to what appears to be the primary source for these etymologies: ただし、戦国期以前には「小坂」や「尾坂」といった表記が見られるため、「大きな坂」という意味ではなく、「オ(オホ)」は接頭語で「サカ」が傾斜地の意味と思われる。

It should be noted that none of the sources are or even reference any of the established 地名辞典, so I would not necessarily trust any of these etymologies. But as others have pointed out, the purpose of the map is not scholarly, but simply to amuse.

David C. said,

August 5, 2020 @ 12:08 am

@Kristin, good point. Seemed too obvious a point for them to miss. They even reference Ooita in their etymology explanation for Osaka, which they note Includes a meaning for great. Wikipedia cites a blog post that suggests Oosaka and Osaka were used all over Japan and both names were used in this particular place. In any case, the map here “translates” it to Barrow – bypassing the issue altogether.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/大阪

http://www.webchikuma.jp/articles/-/1518

Chris C. said,

August 5, 2020 @ 2:35 am

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, "well" used figuratively to mean "source" dates to Old English. This no doubt accounts for "Sunwell".

David Morris said,

August 5, 2020 @ 4:14 am

In Ben's post, which he links to, he mentions the supposed origin of the word 'kangaroo'. This is almost always attributed to James Cook, but he specifically attributes Sir Joseph Banks with ascertaining the word. (The 'The Straight Dope' post Ben links to mentions Banks.) Banks was aware of the difficulties of eliciting words from an unknown language. He wrote:

"Of their Language I can say very little. Our acquaintance with them was of so short a duration that none of us attempted to use a single word of it to them, consequently the list of words I have given could be got no other manner than by signs enquiring of them what in their Language signified such a thing, a method obnoxious to many mistakes: for instance a man holds in his hand a stone and asks the name of [it]: the Indian may return him for answer either the real name of a stone, one of the properties of it as hardness, roughness, smoothness etc., one of its uses or the name peculiar to some particular species of stone, which name the enquirer immediately sets down as that of a stone. To avoid however as much as Possible this inconvenience Myself and 2 or 3 more got from them as many words as we could, and having noted down those which we though[t] from circumstances we were not mistaken in we compard our lists; those in which all the lists agreed, or rather were contradicted by none, we thought our selves moraly certain not to be mistaken in. Of these my list cheefly consists, some only being added that were in only one list such as from the ease with which signs might be contrivd to ask them were thought little less certain than the others."

Cook recorded 60 words, Banks 34 and Banks's botanical artist Sydney Parkinson 147, with some overlap between two or three lists. By that stage they were reasonably well-versed in recording words, having done so in Tahiti and New Zealand as well.

Tom Dawkes said,

August 5, 2020 @ 5:25 am

I would have thought you could plausibly transform Hokkaido — 北海道 — into 'Norway', ignoring 海.

Rodger C said,

August 5, 2020 @ 8:21 am

I think "based on" and "based off" mean basically just the same thing, just a different metaphor.

Yes, an image of location has been replaced with one of motion. Similarly "centered around" for "centered on." It's them action-oriented young folks again.

AG said,

August 5, 2020 @ 8:31 am

Can someone explain why they would say that "Akita has nothing to do with autumn", and then call it "sadfield"? The wikipedia entry on the etymologies of prefectures says something about an older meaning of "wetland", but that doesn't seem to be what happened here. In general so far I find the whole thing too based on strange or hard-to-trace choices by the maker.

Rodger C said,

August 5, 2020 @ 10:02 am

AG, they're probably playing on the meaning of "sad" as "moist."

Mark F. said,

August 5, 2020 @ 11:56 am

When I saw "Sunwell", I thought, "Oh, Nihon must mean 'sun-source'." (Sort of like "inkwell".) So that first choice seems reasonable enough to me.

cameron said,

August 5, 2020 @ 3:53 pm

"Sunwell" does make sense, but "Sunspring" would have been better.

Chris Button said,

August 5, 2020 @ 11:19 pm

@ David C

So Ōsaka 大坂 "big hill" was originally Osaka 小坂 "small hill". Fascinating!

krogerfoot said,

August 6, 2020 @ 12:47 am

AG, the creator points out that the names come from the etymology of the Japanese place names, which often originate from meanings unrelated to the modern kanji they're written with now. Akita's name 秋田 is "autumn field," but the original name was 飽田, "sated field." 飽 aki has come to mean "oversatiated, palled; being sick of"; interestingly, the origin of "sad" is also "sated," so the choice of "Sadfield" gives it the same archaic feeling that Japanese readers get from seeing the original name of Akita—a perfectly normal-sounding name in the past that has taken on an oddly gloomy modern meaning.

I love the map and feel like some of the carping about the creator's choices misunderstand or overlook the clearly explained point of the project. I certainly don't see any lack of expertise in either Japanese or archaic English.

I thought it would be fun to imagine a Japan rendered into American-sounding names, with Amerindian languages filtered through English, Spanish, and French, using elements like Lakota minne- for 川・河 kawa, for example. After trying for some time to come up with even one example, I realized what a crazy quilt American place names are and how half the map would seem to consist of comical names of fictional summer camps from 1960s comedy routines.

James Kabala said,

August 6, 2020 @ 10:03 am

I agree with F that a true purist would have Ainu names in Welsh – and maybe Chinese-derived names (are there any? – my knowledge here is close to nil) would be an excuse to bring in chester/caster names, without which no psuedo-English map seems quite complete. I also kind of think that in remote rural areas kirk would be better than church.

Obviously these are quibbles about a masterpiece far beyond my abilities.

Terpomo said,

August 6, 2020 @ 11:07 am

I strongly encourage the other readers here to check out u/topherette's other submissions, they've done all sorts of interesting etymologically reconstructed maps like this one. There are also some other people who have published Anglicized maps, mostly on r/anglish- and that sub's a whole fascinating linguistic experience on its own!