Bats in Chinese language and culture: Early Sinitic reconstructions

« previous post | next post »

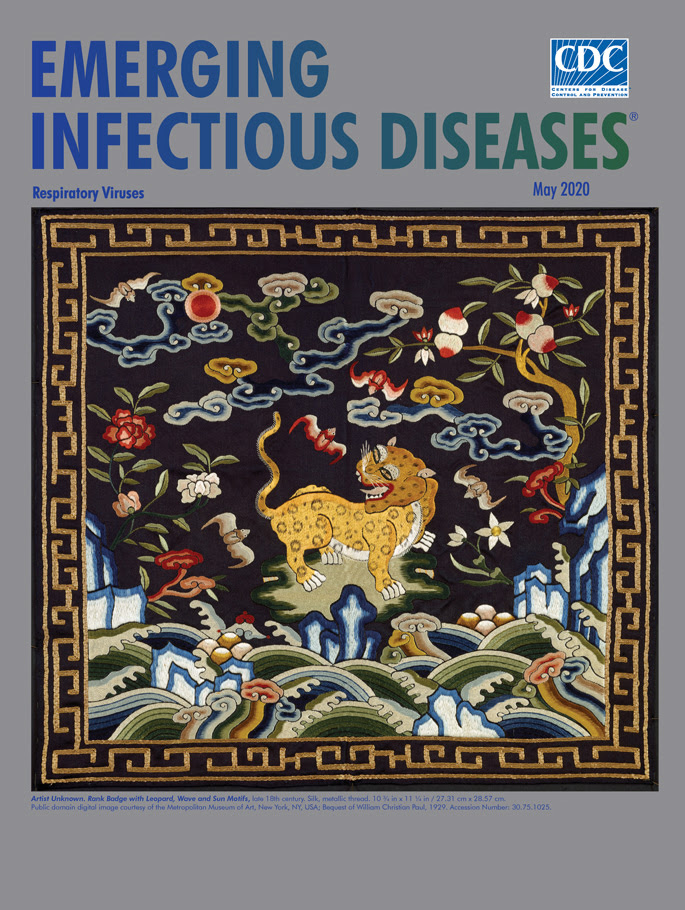

The May 2020 issue of a scientific journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, shows a rank badge of Qing Dynasty officialdom. There are five bats in this piece of ornate embroidery (can you spot them?):

Artist Unknown. Rank Badge with Leopard, Wave and Sun Motifs, late 18th century. Silk, metallic thread. 10 3/4 in x 11 1/4 in / 27.31 cm x 28.57 cm. Public domain digital image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.; Bequest of William Christian Paul, 1929. Accession no.30.75.1025.

(Source)

I have no stake in or knowledge of whether bats were involved in the zoonotic transmission of COVID-19 to human beings in Wuhan, Hubei, China, but they certainly have been in the news quite a bit lately with regard to the pandemic.

Now why would officials in pre-modern China want to sport such loathsome (to some) creatures as bats on their rank badges? The answer is simple: the word for "bat" in Sinitic is biānfú / biǎnfú 蝙蝠, the second syllable of which is homophonous with fú 福 ("blessing; good fortune; bliss"). And this explains why five blessings were featured in Chinese texts already more than two millennia ago. So much for the cultural symbolism.

The linguistic aspects of biānfú / biǎnfú 蝙蝠 ("bat") are even more interesting, at least for readers of Language Log. You will note that, although this is an old word, dating back to around the Han period (206 BC–220 AD), before that it was a monosyllable, just fú 蝠 ("bat"). This is the very common phenomenon of disyllabicization in the development of Sinitic that we have discussed many times (see "Selected Readings", section 2 for some examples).

Biānfú / biǎnfú 蝙蝠 ("bat") is said to be:

an alliterative augmentation of 蝠 (OC *pɯɡ, “bat”), from Proto-Sino-Tibetan *baːk (“bat”). Cognate with Mizo bâk (“bat”).

(source)

This reminds me of an interesting phonological development that took place in the history of the English word "bat":

flying mouse-like mammal (order Chiroptera), 1570s, a dialectal alteration of Middle English bakke (early 14c.), which is probably related to Old Swedish natbakka, Old Danish nathbakkæ "night bat," and Old Norse leðrblaka "bat," literally "leather flapper," from Proto-Germanic *blak-, from PIE root *bhlag- "to strike" (see flagellum). If so, the original sense of the animal name likely was "flapper." The shift from -k- to -t- may have come through confusion of bakke with Latin blatta "moth, nocturnal insect."

(source)

If you're feeling a bit batty lately or think other people have bats in the belfry, it's no wonder how stir crazy we've all become from being cooped up in our caves week after week.

Selected readings

1. Old Sinitic reconstructions

- "Chinese transcriptions of Indic terms in Buddhist translations of the 2nd c. AD" (4/20/20)

- "Archeological and linguistic evidence for the wheel in East Asia" (3/11/20)

- "Horses, soma, riddles, magi, and animal style art in southern China" (11/11/19)

- "Of horse riding and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (4/21/19)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (3/8/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 2" (3/12/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 3" (3/16/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 4" (3/24/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 5" (3/28/16)

- "Of armaments and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 6" (12/23/17)

- "Of shumai and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (7/19/16)

- "Of felt hats, feathers, macaroni, and weasels" (3/13/16)

- "GA" (8/6/17)

- "Of dogs and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (3/17/18)

- "Of ganders, geese, and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (10/29/18)

- "Eurasian eureka" (9/12/16)

- "Of knots, pimples, and Sinitic reconstructions" (11/12/18)

- "Of jackal and hide and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/16/18)

- "Of reindeer and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/23/18)

- "Galactic glimmers: of milk and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (1/18/19)

- "An early fourth century AD historical puzzle involving a Caucasian people in North China" (1/25/18)

- "Thai 'khwan' ('soul') and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (1/28/19)

- "Sinitic for "iron" in Balto-Slavic" (2/15/19)

- "Language vs. script" (11/21/16)

2. Binoms, dimidiation, and disyllabicization

- "An early fourth century AD historical puzzle involving a Caucasian people in North China" (1/25/18)

- "Of reindeer and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (12/23/18)

- "Of knots, pimples, and Sinitic reconstructions" (11/12/18)

- "Water chestnuts are not horse hooves" (6/29/19)

- "'Butterfly' words as a source of etymological confusion" (1/28/16)

3. Bats

- "BCI’s FAQ on Bats and Covid-19", Bat Conservation International, Last updated on April 24, 2020 Published on April 24, 2020, Written by Admin

- "WeChat COVID-19 ditty" (4/23/20)

- "Thoroughly earthy" (4/13/17)

- "Language vs. script" (11/21/16)

[Thanks to Chau Wu and Diana Shuheng Zhang]

Philip Taylor said,

April 28, 2020 @ 12:12 pm

"Stir-crazy" indeed. So stir-crazy, in fact, that, being aware of our esteemed author's [1] predilection for omitting hyphens where I would automatically insert them), I read the second part of his final sentence as "it's no wonder how stir crazy we've all become from being co-oped up in our caves week after week" and then wondered what "to be co-op[p]ed up" meant …

——–

[1] and his fellow countrymen's, of course.

Victor Mair said,

April 28, 2020 @ 12:44 pm

I like hyphens, but one wasn't called for in the last sentence of the post.

Philip Taylor said,

April 28, 2020 @ 2:15 pm

Yes, that was exactly my point (perhaps poorly made) — no hyphen was called for, but my mind subconsciously inserted one because it had become habituated to so doing in your (e.g.,) "coworkers", "coordinates" and so on, even though none was required in this case.

cameron said,

April 28, 2020 @ 6:09 pm

Note that ME "bakke" is preserved somewhat more clearly in the Scots "baukie", with the quaint variant "baukie-bird" showing the same kind of reduplication referred to in the OP.

Chris Button said,

April 28, 2020 @ 7:33 pm

The Northern Kuki-Chin forms (of which Mizo is one) are really irregular with this word.

Chris Button said,

April 28, 2020 @ 11:15 pm

Probably also worth pointing out that the tone of the Mizo form itself is anomalous since the low-rising tone (which seems to be being transcribed with a circumflex here) should regularly be a high-falling tone on a closed syllable of this type.

Luce (1968) has a Khualsim form pɐlak (I'll leave the tone unmarked), which suggests that most Northern Chin languages fused an earlier binomial form together. That binomial form compares fairly well with some of the Mon-Khmer forms in Shorto (2006:161).

Chris Button said,

April 28, 2020 @ 11:17 pm

Sorry–that should be Luce (1962) in his unpublished "Common Form in Burma Chin Languages"