Archive for Language and the law

March 30, 2019 @ 10:11 am· Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and the law

Literally. Kate Bernot, "Please let New Orleans' "Huge Ass Beer" lawsuit reach the Supreme Court", The Takeout 3/1/2019:

Per The New Orleans Advocate, the trademark for Huge Ass Beers belongs to one Nicholas S. Karno #1 Inc., which operates multiple Bourbon Street bars. Said bars—the Steak Pit, Prohibition, and Cornet—offer oversized and novelty pours of beer in branded Huge Ass Beer mugs. […]

But Huge Ass Beer bars’ operator Billie Karno this week filed a lawsuit alleging that other Bourbon Street bars have violated his Huge Ass Beer trademark by selling to-go cups advertising “Giant Ass Beer.” Those bars—Beerfest, Voodoo Vibe, and Sing Sing—plus a strip club called Stiletto’s, are operated by Pamela Olano and Guy Olano Jr. Karno seeks an end to marketing materials bearing the name Giant Ass Beers as well as damages.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 20, 2019 @ 11:13 am· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Words words words

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

New URL for COFEA and COEME: https://lawcorpus.byu.edu.

This post on what arms means will follow the pattern of my post on bear. I’ll start by reviewing what the Supreme Court said about the topic in District of Columbia v. Heller. I’ll then turn to the Oxford English Dictionary for a look at how arms was used over the history of English up through the end of the 18th century, when the Second Amendment was proposed and ratified.. And finally, I’ll discuss the corpus data.

Justice Scalia’s majority opinion had this to say about what arms meant:

The 18th-century meaning [of arms] is no different from the meaning today. The 1773 edition of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary defined ‘‘arms’’ as ‘‘[w]eapons of offence, or armour of defence.’’ Timothy Cunningham’s important 1771 legal dictionary defined ‘‘arms’’ as ‘‘any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another.’’ [citations omitted]

As was true of what Scalia said about the meaning of bear, this summary was basically correct as far as it went, but was also a major oversimplification.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 9, 2019 @ 9:11 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Errors, Language and the law, Spelling

Is there a mistake here?

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 29, 2019 @ 8:03 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Research tools, Words words words

From the Washington Post:

The study is a corpus analysis performed by Jesse Egbert, a corpus linguist at Northern Arizona University and Clark Cunningham, a law professor who did work in law and linguistics from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s (link, link, link, link), including co-authoring an article with Chuck Fillmore that was what really opened my eyes to the power of linguistics in analyzing issues of word meaning.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

December 16, 2018 @ 3:30 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Words words words

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

New URL for COFEA and COEME: https://lawcorpus.byu.edu.

Starting with this post, I’m (finally) getting to the meat of what I’ve called “the coming corpus-based reexamination of the Second Amendment.” The plan, as I’ve said before, is to more or less mirror the structure of the Supreme Court’s analysis of keep and bear arms. This post will focus on bear, and subsequent posts will focus separately on arms, bear arms, and keep and bear arms; I won’t be separately discussing keep arms because I have nothing to say about it. [Update: If you're confused about why I'm following this approach, as one of the commenters was, I've offered an explanation at the end of the post.]

In discussing the meaning of the verb bear, Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller said, “At the time of the founding, as now, to ‘bear’ meant to ‘carry.’’’ That statement was backed up by citations to distinguished lexicographic authority—Samuel Johnson, Noah Webster, Thomas Sheridan, and the OED—but evidence that was not readily available when Heller was decided shows that Scalia’s statement was very much an oversimplification. Although bear was sometimes used in the way that Scalia described, it was not synonymous with carry and its overall pattern of use was quite different.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

November 3, 2018 @ 5:21 am· Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and the law

From Jonathan Weinberg:

An update to "'100% grated parmesan cheese'" (9/5/2017):

In which the court explains that it can blow off the affidavit of Anne Curzan and Ezra Keshet of the University of Michigan that only one interpretation of the phrase “100% grated Parmesan cheese” is plausible in context, and the affidavit of Kyle Johnson of UM-Amherst that the phrase has only one semantically and pragmatically salient interpretation, because “a reasonable consumer -— the touchstone for analysis under the consumer fraud statutes -— does not approach or interpret language in the manner of a linguistics professor.” Aargh.

The new decision has been covered by Rebecca Tushnet at the 43(B) blog ("Post-parmesan: 100% grated parmesan still doesn't have to be 100% grated parmesan, court reiterates", 11/2/2018). (The affidavits — indeed, the names of the experts — don’t appear in the decision or in Rebecca’s writeup, but I pulled them off Pacer.)

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

October 21, 2018 @ 11:05 am· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Ambiguity, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Words words words

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

In my last post (longer ago than I care to admit), I offered a very brief introduction to corpus analysis and used corpus data on the word keep as the raw material for a demonstration of corpus analysis in action. One of my reasons for doing that was to talk about the approach to word meaning that I think is appropriate when using corpus linguistics in legal interpretation.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 9, 2018 @ 1:28 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

With this post, I begin my examination of the corpus data regarding the phrase keep and bear arms. My plan is to start at the level of the individual words, keep, bear, and arms, then proceed to the simple verb phrases keep arms and bear arms, and finally deal with the whole phrase keep and bear arms. I start in this post and the next one with keep.

As you may recall from my last post about the Second Amendment, Justice Scalia's majority opinion in D.C. v. Heller had this to say about the meaning of keep: "[Samuel] Johnson defined 'keep' as, most relevantly, '[t]o retain; not to lose,' and '[t]o have in custody.' Webster defined it as '[t]o hold; to retain in one's power or possession.'" While those definitions could be improved on, I think that for purposes of this discussion, they adequately explain what keep means when it's used in the phrase keep arms. So I'm not going to discuss that data with an eye to criticizing this portion of the Heller opinion.

Instead, I'm going to use the data for keep as the raw material for an introduction to the nuts and bolts of corpus analysis. I suspect that many people reading this won't have had any first-hand experience working with corpus data, or even any exposure to it. Hopefully this quick introduction will enable those people to better understand what I'm talking about when I start to deal with the data that does raise questions about the Supreme Court's analysis.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

July 25, 2018 @ 4:54 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Ambiguity, ambiguity, coordination, Grammar, Language and the law, relative clauses, Syntax

Last week the Washington Post published an op-ed by Michael Anton arguing that the United States should do away with birthright citizenship—the principle that anyone born in the United States is a U.S. citizen, even if their parents are foreign-born noncitizens. The op-ed has attracted a lot of attention from people on both the left and the right, and by “attention” I mean “condemnation”. (E.g., Garrett Epps at The Atlantic, Mark Joseph Stern at Slate, Dan Drezner at the Washington Post, Robert Tracinski at The Federalist, Alex Nowraseth at The American Conservative, and Jonathan Adler at Volokh Conspiracy. See also this Vox explainer.)

The criticism both on on Anton’s nativism, but also on his interpretation of the 14th Amendment, on which birthright citizenship is based. One of the interpretive moves for which Anton has been criticized is his handling of a statement made on the floor of the Senate while the proposed text of the 14th Amendment was being debated. And that dispute turns on the resolution of a syntactic ambiguity.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 22, 2018 @ 11:44 am· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Bilingualism, Language and medicine, Language and the law, Language and travel

Let me try to pull together the information from my previous two posts, and add information that I'm seeing on Twitter. I will update this as I get more information.

Service-providers looking for interpreters. Much of the interpreting that is needed can be done by phone, so geographic location shouldn't be an issue.

RAICES: volunteer@raicestexas.org.

American Immigration Council. The person to contact is Crystal Massey, but the website doesn't give her email address. The general "Contact Us" page is here. (Added June 24, 2018.)

Service-providers that might need interpreters. These are names of groups that someone posted on Twitter; I don't know whether they're actually looking for interpreters.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 22, 2018 @ 1:45 am· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Bilingualism, Language and medicine, Language and the law, Language and travel, Translation

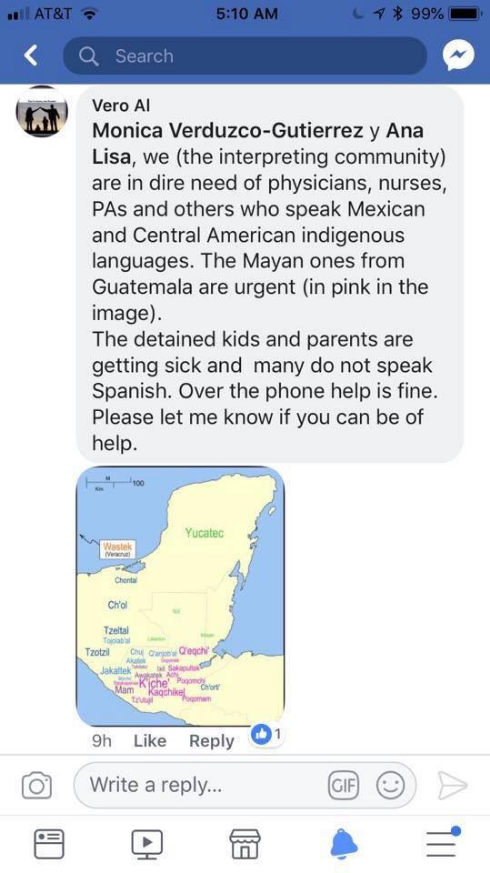

In addition interpreters being needed to help detainees communicate with their lawyers, there is an urgent need for medical personnel who can speak Central American indigenous languages (or, failing that, presumably for interpreters to work with English- and Spanish-speaking medical personnel). This is a Facebook post that Emily Bender has sent me:

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

June 10, 2018 @ 11:36 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Language and the law, Words words words

[An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.]

Before I get into the corpus data (next post, I promise), I want to set the stage by talking a bit about the Heller decision. Since the purpose of this series of posts is to show the ways in which the corpus data casts doubt on the Supreme Court's interpretation of keep and bear arms, I'm going to review the parts of the decision that are most relevant to that purpose. I'm also going to point out several ways in which I think the Court's linguistic analysis is flawed even without considering the corpus data. Although that wasn't part of my plans when I began these posts, this project has led me to read Heller more closely than I had done before and therefore to see flaws that had previously escaped my notice. And I think that being aware of those flaws will be important when the time comes to decide whether and to what extent the data undermines Heller's analysis.

The Second Amendment's structure

As is well known (and as has been discussed previously on Language Log here, here, and here), the Second Amendment is unusual in that it is divided into two distinct parts, which the Court in Heller called the "prefatory clause" and the "operative clause":

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink