Citizenship and syntax (updated, and updated again)

« previous post | next post »

Last week the Washington Post published an op-ed by Michael Anton arguing that the United States should do away with birthright citizenship—the principle that anyone born in the United States is a U.S. citizen, even if their parents are foreign-born noncitizens. The op-ed has attracted a lot of attention from people on both the left and the right, and by “attention” I mean “condemnation”. (E.g., Garrett Epps at The Atlantic, Mark Joseph Stern at Slate, Dan Drezner at the Washington Post, Robert Tracinski at The Federalist, Alex Nowraseth at The American Conservative, and Jonathan Adler at Volokh Conspiracy. See also this Vox explainer.)

The criticism both on on Anton’s nativism, but also on his interpretation of the 14th Amendment, on which birthright citizenship is based. One of the interpretive moves for which Anton has been criticized is his handling of a statement made on the floor of the Senate while the proposed text of the 14th Amendment was being debated. And that dispute turns on the resolution of a syntactic ambiguity.

This is relevant part of the 14th Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

The Supreme Court held in 1898 that, with narrow exceptions, birthright citizenship extends to children born in the United States whose parents were noncitizen immigrants. But Anton contends that “the entire case for birthright citizenship is based on a deliberate misreading of the 14th Amendment”.

Anton’s argument has to do with the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction [of the United States]”. In support of this argument that U.S.-born children of immigrants aren’t within the jurisdiction of the United States, Anton points to a statement by Sen. Jacob Howard during the Senate debate.

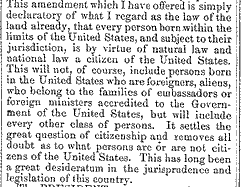

Howard said that the grant of citizenship that was to be conferred by the language I’ve quoted did not extent to “persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers” (link). Here is Howard’s statement as it appears in the Congressional Globe, which provided the record of Congress’s proceedings:

When Anton quoted Howard, however, he altered the text. Specifically, he inserted the word or in brackets:

Sen. Jacob Howard of Michigan, a sponsor of the clause, further clarified that the amendment explicitly excludes from citizenship “persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, [or] who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.” [bracketing by Anton; boldfacing added]

Anton is not the first person to oppose the current interpretation of birthright citizenship, and he is likewise not the first opponent to make this insertion. The insertion was made in a 2015 article in National Review, which Anton credited as the source of his argument. And that article, in turn, was not the first time that “[or]” was inserted in the quote from Howard. The author of the article, Edward Erler, had previously done so in an article published in 2008. After that, several other conservative writers did the same (e.g., Mark Alexander at The Patriot Post (2010), Joe Wolverton at The New American (2011), John Eastman, at National Review (2015), and Mark Pulliam at Law and Liberty (2015)).

As far as I can tell, the first time anybody commented on these insertions was in 2015, when Mark Pulliam was accused, in the comments on his post, of misquoting Howard. Pulliam denied the accusation and said that he had made the insertion merely “to make the statement coherent in context”.

Then in 2016, John Eastman’s use of the altered quote was challenged by Linda Chavez (who had served as staff director of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights under Ronald Reagan). In an extended response to Eastman, which led to an even more extended back-and-forth with him, Chavez wrote, “In his National Review article, Eastman cleverly inserts his own ‘[or]’ before the restrictive clause in Howard’s quotation. But no such ‘or’ is in the original! Neither is one intended, as the full debate makes clear.”

In answering Chavez, Eastman said (as had Pulliam before him) that he was merely trying to clarify what he thought was Howard’s intended meaning. He also argued that Chavez had erred “by treating the notes of the congressional record as though it were a verbatim transcript, capturing both every word and every nuance that was spoken.” But interestingly, Pulliam had said precisely the opposite in response to the criticism of his use of the altered quote. According to Pulliam, “The debates of the 39th Congress are transcribed verbatim, with grammatical anomalies, gaps in syntax, and some puzzling contradictions.” (It seems to me that Pulliam has the better of this disagreement. By the time of the debate on the 14th Amendment, proceedings on the Senate floor were recorded by shorthand reporters, so they were presumably at least intended to be verbatim transcripts. Of course, that doesn’t mean that there were no transcription errors, but if someone wants to rely on the Congressional Globe as a record of the Congressional proceedings, we have no option but to assume that it is accurate.)

Meanwhile, back here in the present, Anton’s alteration of Senator Howard’s statement has been widely condemned. Here is some of what Anton’s critics have said:

Anton quietly supplied the word or to make it appear that two different definitions were being offered—either a diplomat or a foreigner. But in fact, what Howard was saying was simple: American-born children of diplomats are not birthright citizens—because they and their parents are immune from American laws. [Garrett Epps.]

By adding the word or, Anton creates the false impression that Howard spoke of three different groups—“foreigners,” “aliens,” and the children of ambassadors. But in reality, Howard described a single group: the children of ambassadors, whom he characterized (correctly) as “foreigners” and “aliens.” Howard did not intend to exclude all children of foreigners from citizenship. He merely noted that, under long-standing international custom, the offspring of diplomats abroad do not receive the citizenship of their host country. [Mark Joseph Stern.]

Anton wants the reader to believe that [Howard] is listing distinct categories of individuals. What [Howard] was actually doing was listing synonyms to describe the same category of individuals, namely the children of foreign officials. [Daniel Drezner.]

Two years earlier, Linda Chavez had made essentially the same point in her response to John Eastman:

The words “foreigners, aliens,” are in apposition to each other; that is, they mean the same thing and are repeated for effect. More importantly, the words do not stand alone; they are followed by a restrictive modifying clause: “who belong to families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.” Howard intended to exclude only those foreigners (i.e. aliens) who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers; otherwise, as he clearly stated, all other persons born in the U.S. were to be considered citizens by birth.

Anton has now responded to his critics and in his response he addresses the issue of the inserted “[or]”. His basic position is the same as Pulliam’s and Eastman’s: he was just making clear what he thinks Senator Howard meant. However, Anton goes into more detail than Pulliam and Eastman did, undertaking a grammatical analysis that he offers as justification for the insertion. And as Eastman had done, Anton questioned the Congressional Globe’s accuracy:

It is necessary to note that this quote (and most of those that follow) come from the Congressional Globe, an ancestor to the Congressional Record, which records Congressional debates. Unless otherwise noted, all the quotes that follow are from the Globe’s account of the Senate the debate on the 14th Amendment, May 30th, 1866. They do not purport to be exact transcripts, especially with regard to punctuation.

As I’ve said, I think that the Congressional Globe did purport to offer “exact transcripts.” But Anton’s reference to punctuation highlights an important point that I will return to later. Punctuation is purely an artifact of writing; it plays no role in spoken language. As a result, it’s necessary to keep in mind that the punctuation that we see in the Congressional Globe (and any in other transcript of spoken language) was put there by the transcriber.

With that detail out of the way, here is Anton’s explanation for having inserting the “[or]”:

The charge is that the added “or” completely changes the meaning. [Senator Howard’s] intent, it is said, is to exclude from citizenship only those “who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.”

But if that is what was meant, the language would have to read “who are foreigners OR aliens who belong …” To get to the meaning insisted upon, one must not merely add “or” after foreigners, one must also delete both commas. Getting rid of just the first one will not do.

But that’s not what’s in the text. What is there is a list missing its final conjunction. Apples, oranges, bananas. Remembering my high school English, I simply added one for the reader. Apples, oranges, [or] bananas.

[The bracketed insertion of Senator Howard’s is by me; the bracketed or is by Anton.]

Unfortunately for Anton, high school English doesn’t equip one to do the kind of analysis that’s needed here.

Anton describes the word-string foreigners, aliens as “a list” in which the first two items are the nouns foreigners and aliens, and the final item is the relative clause who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers. The traditional grammatical label for what Anton is talking about is not list but series (maybe Anton skipped English class the day they taught that). In linguistics, a variety of different terms are used, including conjoined structures, coordinate structures, and coordinations. But no matter what the label, Anton’s argument flies in the face of is difficult to square with how English grammar works.

Note that I’m not talking about the kind of prescriptive rules that most people think of when they hear the word grammar; this is Language Log after all, and we have standards to uphold. No, I’m using grammar in the way that it’s used in linguistics, as a way to refer to the regularities that characterize the actual speech patterns of native English-speakers.

The problem is that for a series of conjoined elements to be acceptable, generally the elements all have to belong to the same grammatical category. That constraint isn’t remotely satisfied here. Foreigners and aliens are nouns, while who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers is a relative clause. Both foreigners and aliens can function by themselves as the subject of a sentence or the direct object of a verb, while neither of those functions can be performed by who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers:

Foreigners bother Michael Anton.

Aliens bother Michael Anton.

* Who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers bother Michael Anton.

[The asterisk marks the example as being ungrammatical.]

Michael Anton dislikes foreigners.

Michael Anton dislikes aliens.

* Michael Anton dislikes who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.

As noted by The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, the constraint against coordination of items from different grammatical categories is “reflected in the fact that usually either [here, any] of the coordinates could stand alone in place of the whole coordination (with adjustment of agreement features where necessary)” [boldfacing in the original]. But trying that with who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers results in a train wreck:

persons born in the United States who are foreigners

persons born in the United States who are aliens

* persons born in the United States who are who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

So the relative clause who belong to families… can’t possibly be part of a three-element series of which the first two elements are foreigners and aliens. And that’s unsurprising given that the function of relative clauses of this type is to modify nouns. (Speaking technically, their function is to modify noun phrases—a category that includes plural nouns.) In order for the relative clause here to be conjoined with one or more noun phrases, it would be necessary to change who to whoever:

foreigners, aliens, and whoever belongs to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

Update: I have to add a qualification to my discussion above of how relative clauses can and cannot be used. Thanks to Gregory Kusnick's comment on this post, I realize that I was too quick to say that relative clauses beginning with who can't be used as subjects of a sentence or direct objects of a verb. (Stated in more technical terms, the question is whether who can occur as the head of a fused relative clause.) Historically, such usages did exist—e.g., "Who steals my purse steals trash" from Othello (h/t CGEL)—and although they are currently nonstandard and uncommon, they do occur. In fact, the issue has been discussed here by Geoff Pullum ("Can I help who's next") and Mark Liberman ("Fused relative clauses with who").

Nevertheless, I think the suggestion that the relative clause can be understood as being conjoined with foreigners and aliens is implausible. The problem is the unusual context, in which the relative clause who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers is by hypothesis embedded in the conjoined structure foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families…, which is in turn embedded in another relative clause (who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families…). So even if who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers standing alone might be acceptable as a fused relative in some other context, I think that in the context of Senator Howard's statement, such a reading would be extremely unnatural.

Given all of this, if we ignore the absence of a conjunction between foreign and aliens, and assume that Anton is correct in treating foreigners and aliens as a series of conjoined nouns, there are only three ways to interpret Senator Howard’s statement.

First, the relative clause could be understood as modifying both foreigners and aliens. But that wouldn’t give Anton the reading that he wants; for his interpretation to work, one of those nouns has to be left unmodified.

Second, the relative clause could be interpreted as modifying only aliens. That would result in the interpretation that Anton wants, but it would do so only by creating a redundancy. An alien who belongs the family of an ambassador or foreign minister is by definition a foreigner. On this reading, therefore, the phrase aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers was unnecessary. And even apart from that, Anton’s interpretation ignores the fact that there is no conjunction between foreigners and aliens. Without a conjunction, the phrasing of Senator Howard’s statement would be quite an awkward way to express the meaning that Anton advocates.

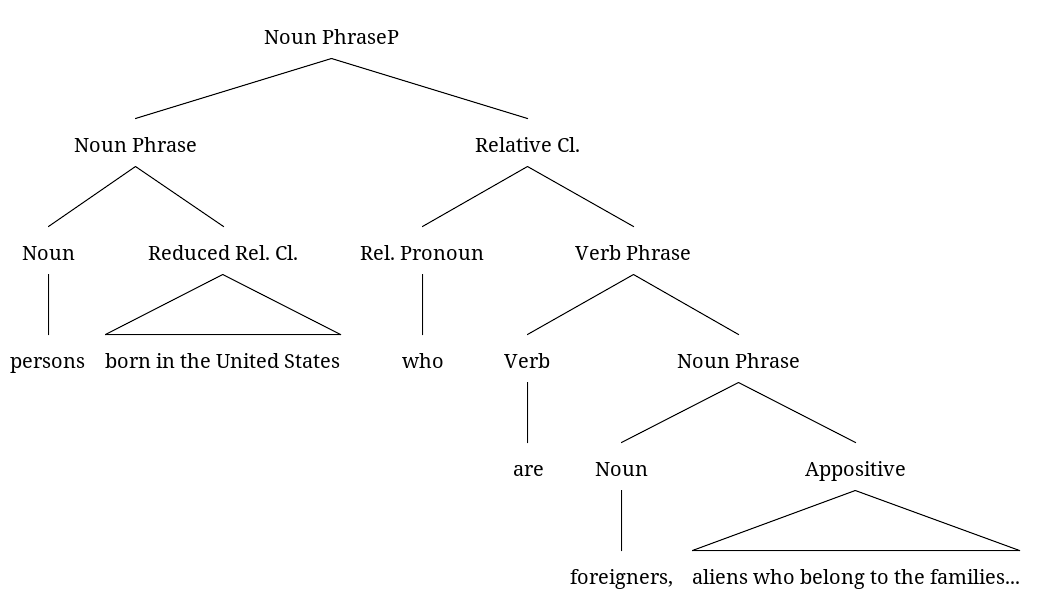

Third, the relative clause could be interpreted as modifying persons born in the United States, and therefore as being coordinated with who are foreigners, aliens. [Clarification: On this interpretation, who belong to the families… would not be coordinated with foreigners, aliens, but foreigners and aliens would still be coordinated with each other.] This would result in the following structure, with persons born in the United States being modified by two coordinated relative clauses—who are foreigners, aliens and who belong to the families of ambassadors of foreign ministers. That structure is depicted in this tree diagram (click to enlarge):

This structure would generate the interpretation that Anton advocates, but with no conjunction between foreigners and aliens, it is, as I’ve just said, quite unnatural. Although coordination without a conjunction can work sometimes—it’s called asyndetic coordination—I don’t think this is one of those times. Among other factors, asyndetic coordination strikes me as more of a rhetorical device than a syntactic workhorse. So this interpretation doesn’t really work unless another “[or]” is inserted, this time between foreigners and aliens. But if it’s hard to justify inserting even one “[or],” then justifying the insertion of two of them—within the space of three words—seems way out of bounds.

With all of the problems I’ve identified, it’s not possible to make sense of Senator Howard’s unaltered statement if we accept Anton’s characterization of foreigners and aliens as being coordinated with one another. And once we abandon that characterization, it seems to me that the only viable interpretation is the one advanced by Linda Chavez said in her response to John Eastman: “The words ‘foreigners, aliens’ are in apposition to each other; that is, they mean the same thing and are repeated for effect.”

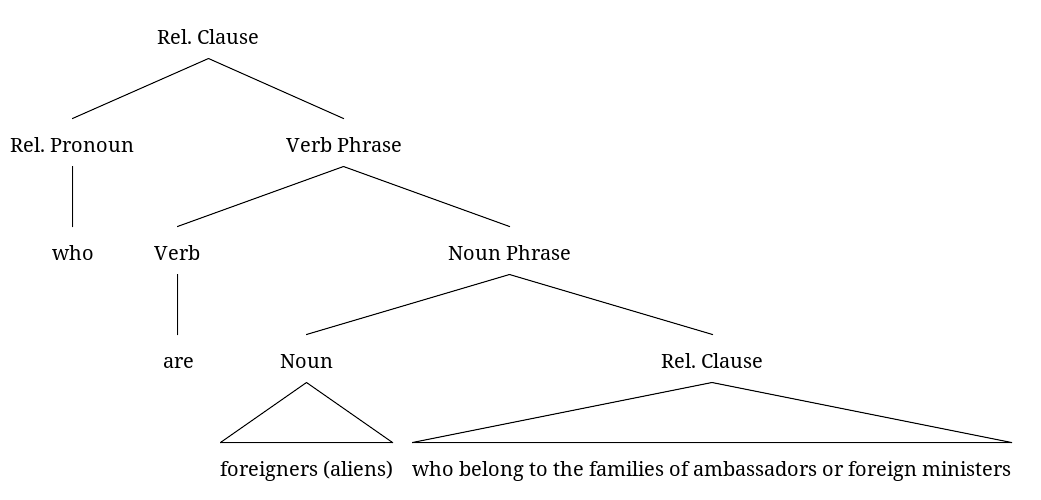

Update: On this interpretation, who belong to the families… would modify foreigners, with aliens being regarded as merely elaborating foreigners rather than describing a separate category. The resulting structure would look like this:

Further update: Be sure to read through (or skip ahead) to the end of the post for an alternative I hadn't initially considered, which on reflection I think is probably correct.

While this interpretation does not exactly jump out at you when you read Howard’s statement, that’s because of how the text is punctuated. With commas on either side of aliens, the word-string foreigners, aliens, is punctuated the same way that it would be punctuated if it were in fact part of a series of conjoined nouns. And because most instances of the pattern NOUN + COMMA + NOUN + COMMA fall into that category, one’s first reaction is naturally to construe this particular word-string that way. Overcoming that initial reaction requires some mental effort.

One’s reaction would be different if the word-string had been punctuated using dashes or parentheses rather than commas:

persons born in the United States who are foreigners—aliens—who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

persons born in the United States who are foreigners (aliens) who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

With punctuation like that, it would not be possible to read foreigners, aliens as part of a coordinated series.

OK, but can commas be used to mark apposition? Yes they can, and here is an example:

The author whose op-ed I am discussing here, Michael Anton, has been criticized from both sides of the political spectrum.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language provides the following sentence as an illustration of the use of commas to mark what it calls asyndetic subclausal supplementation (a category that includes appositives):

Bishop Terry Lloyd, the only Welshman in the college, had opposed the plan. [p. 1471; see also p. 1357]

And if you’re a snoot who doesn’t trust the anything-goes libertines who wrote CGEL, hopefully you’ll accept the statement by Bryan Garner that “commas frame an appositive” unless the appositive is necessary to identify the referent of the noun to which the appositive relates. (That’s from Garner’s Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation.)

In any case, it’s a mistake to rely on the use of commas in the text rather than dashes or parentheses. As I’ve said, the punctuation that appears in the Congressional Globe was added by the shorthand reporter who created the transcript. It’s a pretty good bet that Senator Howard didn’t say “foreigners comma aliens comma”.

What about the fact that if aliens is interpreted as an appositive, it is redundant? When I discussed the possibility of interpreting who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers… as modifying only aliens, one of my objections was that doing so would result in a redundancy (a different redundancy, but a redundancy just the same). Why isn’t the same true of interpreting aliens as an appositive?

The reason it’s not true, it seems to me, is that in the case of the apposition here, the redundancy is a feature, not a bug. The redundancy is precisely the reason for using the appositive structure in the first place. In the context here, “foreigners, aliens,…” is roughly equivalent to saying “foreigners—i.e., aliens—…”. In contrast, the redundancy associated with the interpretation I’ve rejected serves no communicative function.

So to sum up, I don’t think that inserting “[or]” into Senator Howard’s statement can be justified as mere clarification. And even if Anton believed otherwise, it was wrong to make the insertion without flagging the interpretive issue more explicitly.

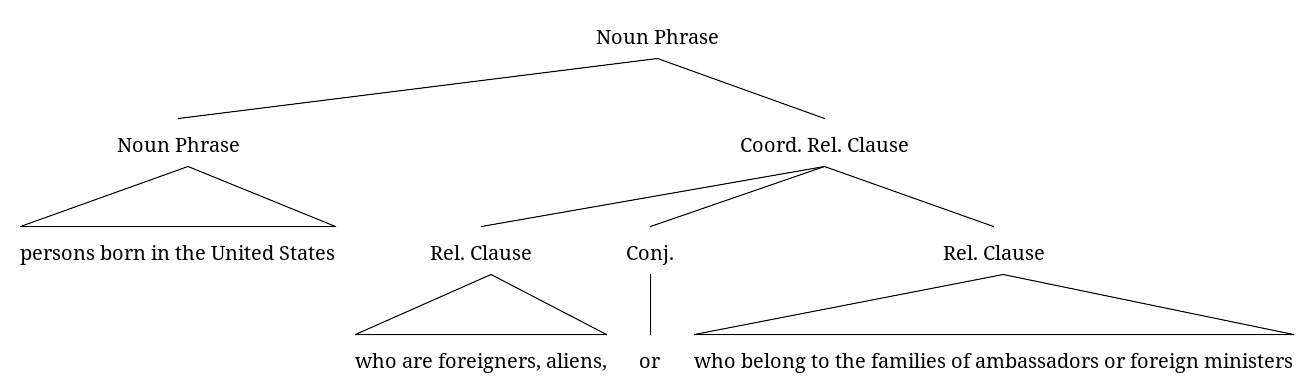

Update: An different interpretation has been proposed by several people in the comments; it also involves apposition, but in a different way, and I now think it is probably correct.

cameron was the first person to articulate this interpretation:

The term "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers, accredited to the government of the United States" is not in apposition to the term "foreigners" – as if these two terms are meant to be synonymous. The first part of the apposition is the phrase "persons born in the United States who are foreigners". The term "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers, accredited to the government of the United States" is thus meant to clarify exactly what is meant by the phrase "persons born in the United States who are foreigners". That latter phrase is potentially oxymoronic in the context of a discussion of birthright citizenship, so he clarified what he meant by it. The term "foreigners" is not being defined or clarified.

Later, Gwen Katz wrote:

The natural meaning to me is to have "who belong to the families.." modifying "aliens" and have the entire phrase "aliens who belong to the families…" in apposition to "foreigners."

And then Paul Kay elaborated on this idea:

I think all one needs to do to make the original, not only grammatical and idiomatic, but also in keeping with the other indications of the original intent (as noted by outeast, for example) is to imagine that the second comma would be removed by an editor today as erroneously setting off a restrictive relative clause. (I think this is essentially Gwen Katz's idea.) Removing that comma we have, "This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers." The appositive noun phrase "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" clarifies how somebody can be born in the U.S. but nevertheless a foreigner not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. Putting a comma before a restrictive relative clause seems to me like an easy mistake to make; for that matter. I don't know anything about punctuational practice in the mid-19th century. Maybe punctuation rules were looser then.

This yields the following structure:  Postscript

Postscript

In the wake of the criticism of Anton, the online version of the 2015 National Review article that Anton relied on was revised to remove the insertion of “[or]”, and an editor’s note was added, stating, “This article has been emended since its original posting, to remove a bracketed insertion to a quotation that arguably changed its meaning.”

The Washington Post has posted the following Editor's Note at the top of Michael Anton's op-ed:

Michael Anton inserted the bracketed word “[or]” into a statement made by Michigan Sen. Jacob Howard during debate of the 14th Amendment on May 30, 1866, as recorded in the Congressional Globe. Anton wrote that Howard “clarified that the amendment explicitly excludes from citizenship ‘persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, [or] who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.’ ” Writers before Anton have made the same insertion, and Anton stands by his interpretation of Howard’s statement and maintains that the insertion of the word clarified rather than altered its meaning. You can read his full explanation in a blog post subsequently published by the Claremont Review of Books. Others believe the inserted word changes rather than clarifies the meaning of the quotation. Because the quotation can be read a different way, we should have asked Anton to publish it unaltered and then explain his interpretation rather than publishing it with the inserted word.

Gregory Kusnick said,

July 25, 2018 @ 5:27 pm

W.S. Gilbert seemed to think a relative clause could stand as the subject of a sentence when he wrote "Spoils the child who spares the rod." (H.M.S. Pinafore, "Things are seldom what they seem")

That said, I agree that Anton reads the Howard quote wrong.

[(ng) See my update to the post, taking account of this.]

Michele said,

July 25, 2018 @ 5:50 pm

Thank you for this.

Michael Watts said,

July 25, 2018 @ 5:53 pm

I tend to instinctually agree with the theory that the transcript contains a speech error; it's hard for me to interpret "persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" directly. I feel that some essential markers of how the phrases in that stretch of text relate to each other are missing. That doesn't justify supplying markers that force the text into a preferred meaning, though.

However, I do have an objection to the idea that "persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" simply means "persons born in the United States who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers".

The two competing theories of this text appear to be that

(1) "foreigners", "aliens", and "[people] who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" are three separate list elements; or

(2) "foreigners", "aliens", and "who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" are one and the same thing, repeated three times for rhetorical emphasis.

With appropriate delivery, I might punctuate #2 as something like

But the problem I see with #2 is that, the way I understand English, this interpretation strongly implies that "who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" is a definition of the class of "foreigners" / "aliens", which is nonsense — I am confident that "foreigners", now and at the time, also referred to non-natives who were not known to be related at all to any foreign diplomat.

I tend to agree that regardless of that dispute, "foreigners" and "aliens" are the same thing and were meant to be the same thing in the original text.

David Marjanović said,

July 25, 2018 @ 6:29 pm

Well, if the stenographers punctuated their transcripts, they may have intended to use it to indicate intonation features that they actually heard. But there's obviously not much in the way of testable hypotheses in that direction.

AntC said,

July 25, 2018 @ 6:32 pm

I think that the Congressional Globe did purport to offer “exact transcripts.”

Did the Globe check transcripts with the speakers before publishing? That's common practice with Hansard's reports in the UK.

Never the less, punctuation habits might have shifted.

I'm not really seeing why the niceties anyway: Is the US being overrun by "families of ambassadors or foreign ministers"? Is there some specific family member Anton is trying to exclude or include?

I thought Republicans/Trumpists are worried about nondocumented/illegal immigrants. There's no claim that the children who they're separating from their parents are children of diplomats?

What is the sub-text?

Gregory Kusnick said,

July 25, 2018 @ 7:21 pm

AntC: On the conventional reading, children born in the US of immigrant parents are automatically US citizens, with full rights as such, regardless of whether their parents are documented or not. This arguably creates an incentive for prospective parents to immigrate illegally before having kids.

Anton presumably wants to remove that incentive by concocting a reading in which such children are not citizens and can legitimately be deported along with their parents.

Neal Goldfarb said,

July 25, 2018 @ 7:52 pm

David Marjanović said:

I'm sure that the stenographers did take account of the speaker's prosody in deciding how to punctuate the transcribed text. The problem here has to do with the choice of what punctuation mark to use (e.g, comma versus dash), not the choice of where the marks should be placed.

David P said,

July 25, 2018 @ 8:18 pm

Michael Watts: I'm no lawyer, but what is to me the most natural reading doesn't belong in either of your two categories. What is being defined here is the subset of foreigners who aren't subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. Paraphrasing the quote a little: "The group subject to the jurisdiction of the states does not of course include foreigners who are families of ambassadors…." The families of diplomats notoriously have diplomatic immunity, unlike other foreigners born in the U.S.

It must be said, though, that the settling of the "great question of citizenship" referred to in the last two sentences of the quotation, although successful for a time, appears to be now under attack,

cameron said,

July 25, 2018 @ 11:25 pm

With regard to Michael Watts's comments above: I tend to think the comma after "aliens" is muddying the waters quite a bit. That comma is unnecessary; 19th century writers an editors were very free with commas.

The term "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers, accredited to the government of the United States" is not in apposition to the term "foreigners" – as if these two terms are meant to be synonymous. The first part of the apposition is the phrase "persons born in the United States who are foreigners". The term "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers, accredited to the government of the United States" is thus meant to clarify exactly what is meant by the phrase "persons born in the United States who are foreigners". That latter phrase is potentially oxymoronic in the context of a discussion of birthright citizenship, so he clarified what he meant by it. The term "foreigners" is not being defined or clarified.

tangent said,

July 25, 2018 @ 11:44 pm

"Who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers belong to trash."?

Nah, I can't make that go. It's too long, and the plural "who" doesn't help.

What does Anton want "not within the jurisdiction of the U.S." to mean? Alien immunity parallel to diplomatic immunity? Strange argument altogether.

dainichi said,

July 26, 2018 @ 12:33 am

I wondered the exact same thing as @tangent. I don't know the exact technical meaning of "jurisdiction", but presumably Anton wants certain people to be within the kind of jurisdiction that can deport people, but not the kind of jurisdiction that makes them citizens.

I find Howard's statement strange no matter how it's interpreted. He seems to say "NP is a citizen, but that does not apply to foreigners…". There's some weird redundancy there.

Chris Travers said,

July 26, 2018 @ 1:42 am

Granted there I haven't done the formal analysis you have but it seemed to me when I first read Howard's remarks that he was saying something fairly basic and that the 'or' is not so problematic, but at the same time the quote is heavily abused. So what follows is I think the way an argument over grammar is abused to obscure an argument over substance.

As you note there are three categories of people excluded from citizenship:

1. Foreigners (if they were citizens they wouldn't be foreigners)

2. Aliens (see above)

3. Children born in the US of foreign ambassadors and diplomats.

As I would argue the is indeed implied but it doesn't go where the anti-birthright-citizenship movement thinks it does. The actual argument is over what it means to be subject to jurisdiction. Some important aspects of jurisdiction don't apply to people who are just visiting who we don't extend citizenship to. We don't ask a Saudi tourist if he is has multiple wives as a condition of entry even though bigamy is a crime in all states, for example. But once we assert citizenship then someone is under the jurisdiction of the US.

I would submit the reason why the question of grammar takes over the argument is that a careful assessment of the substance doesn't fully resolve the issue entirely. For example, if we were to change, at some point, our policy on refugees to exclude them for a time from family law issues on the basis that they are temporary guests, then that raises a real question over whether birthright citizenship must be extended to children born during that time of partial immunity. Similarly if Congress were to extend diplomatic immunity to all illegal immigrants, then that might allow Congress not to offer their children citizenship…. And while these hypotheticals seem far-fetched they raise questions I think people would rather avoid discussing.

So they argue over edits and grammar instead.

outeast said,

July 26, 2018 @ 2:02 am

I think that any such close grammatical analysis is rather question-begging because faulty parallelism is utterly commonplace, even in professionally edited and published texts (let alone in speech). I don't think it's possible to have any confidence in any analysis that relies on this.

That said, I agree with the hypothesis that "aliens" is meant as a clarification of "foreigners".

To my mind, the more persuasive argument is that Howard first establishes the two qualifications: "born in the united stats" and "subject to the jurisdiction of the united states". When he then specifies the exclusion of aliens, he says "of course". Why "of course"? Most obviously, it would be because they fail one or both of those tests. Since he's explicitly talking about people who meet the first test ("born in the united states"), the failure must be in the second, i.e. that they are not subject to US jurisdiction. This supports the narrow interpretation that he is talking specifically about people outwith that jurisdiction, i.e. the children of ambassadors etc.

Potentially it could mean citizens of foreign nations, though? It's possible that he meant that people born within the US who remained citizens of another nation would count as "aliens". Would a child born to, say, British-born immigrants have had British citizenship? Was dual citizenship even a thing? I'm not sure how citizenship by birth worked back then, but I suspect that for the children of an immigrant to retain their parents' citizenship would have been a privilege reserved for a minority. In that case, the qualifier might have seemed obvious at the time, and a plausible interpretation could be that people born with foreign citizenship are not automatically US citizens. (That would be odd today because citizenship laws have changed a lot, but it might have made sense then.)

Thoughts, anyone?

GH said,

July 26, 2018 @ 2:37 am

It's trivial, I know, but is it Pullium or Pulliam? They seem to exist in free variation within the article.

@outeast:

In earlier ages it was quite common for different people living in the same state to be subject to different laws depending on their ethnicity. There might be one law for an Englishman, another for a Dane, a third for a Welshman, and so on. (My understanding is that this was partly a matter of discrimination and partly about respecting the traditional laws of each community.)

The Enlightenment tended to reject this approach (notably regarding the Jews), and I believe that's the thinking embodied in the Constitution, but wasn't it nevertheless how Native Americans were largely treated in early US jurisprudence?

Chris said,

July 26, 2018 @ 4:32 am

I propose a different reading from either Anton [or] Goldfarb.

While NG's analysis makes sense out of context, the Congressional Globe goes on to record the discussion of how Howard's comments relate to Native Americans. Howard says (I paraphrase), "of course it doesn't apply to Native Americans because, as we all know, they're foreigners."

This suggests that the series "foreigners, aliens, who…" is not three synonymous things since Howard thinks that there are other categories of excluded foreigner besides children of ambassadors who not subject to US jurisdiction (in relation to the amendment).

I propose that the correct reading would be "…aliens,who [, for example,] belong to…"

Since this is a transcript of spoken English, I think we can accept grammatical violations if context necessitates it.

Rachael said,

July 26, 2018 @ 5:17 am

AntC: Both sides agree that people born to American citizens are American citizens. Both sides agree that people born to visiting ambassadors are not. The debate is about people born to non-ambassador foreigners.

Rachael said,

July 26, 2018 @ 5:26 am

I agree with outeast that faulty parallelism is very common. I'm a proofreader and I encounter it frequently, and sometimes writers don't understand why it's an error when I point it out. And that's in polished writing – I'm sure it's even more common in speech. So I don't think any argument should be built on the assumption that it never happens.

Also, I would guess that the debate in those days was about whether Native Americans and American-born black people were citizens, and if so, "everyone born on American soil" should be understood in the context of that debate, and "apart from foreigners, obviously" understood as an uncontroversial aside.

outeast said,

July 26, 2018 @ 6:07 am

I just scanned further on in the debate, and it *specifically* says that an example would be that the children of Mongolian parents born on US soil would be US citizens. It also says that Native Americans would not, because "they are not … born subject to the jurisdiction of the united states" and are regarded as being "quasi foreign nations." So it looks like the discussion itself clarifies the position: being born on US soil and being subject to US law means being a US citizen, regardless of parental nationality or origin. Being born subject to another jurisdiction is the exclusion.

As an aside, the arguments and objections in that debate echo those we're hearing today very closely. Come on, America: how are you back to 1866?

Andrew Usher said,

July 26, 2018 @ 7:31 am

I think this linguistic analysis is a dead end – we can't be sure how he actually delivered the sentence in speech (and how it would be understood); without the conjunction, which I do presume was not omitted by the reporter, it's ambiguous.

In any case the entire context of the debate is available and should be examined instead if we really care about the original meaning. I don't, because on this issue it's quite apparent that first the issue now is far different than could have been conceived by most Americans at that time, and secondly one's opinion on this issue appears to be determined by one's beliefs about (present-day) illegal immigration, even though some may search for some original meaning to back up their already fixed opinion. (Or, alternatively, support may be based on the desire not to appear 'racist', which is even more impervious to reason.)

To close with a linguistic note, I again express surprise that anyone could ever doubt the grammaticality of 'who steals my purse, steals trash' (seemingly the example always cited here) – although I certainly acknowledge that Shakespeare's English is obsolete and is not a good guide to present grammar, but in this case it does not fail.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com

J.W. Brewer said,

July 26, 2018 @ 11:59 am

Some of the additional colloquy between other Senators referred to in outeast's comment is quoted in the majority opinion in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, the 1898 Supreme Court decision Mr. Goldfarb links to in the original post here. Those who are interested might also look at the dissent in that case as a sort of compendium of what were thought at the time the best arguments against the "birthright" reading of the 14th Amendment, although one should be sensitive to the possibility that the terms of debate might have already shifted between the 1860's and the 1890's.

As to whether we're "back to 1866," that may be an unfair criticism of 1866. The crucial bit of context is that in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War a critical mass of the nation's political class were willing to make a bold rhetorical commitment to ideals of racial equality which their successors proved unable or unwilling (for at least most of the following century, leaving aside the issue of what may have happened more recently than the 1960's) to do the hard work of fully implementing in practice. Indeed, Senator Conness of California, who made some of the remarks the majority opinion relied on for the proposition that the Senate fully understood that the text they were voting on would give birthright citizenship to the US-born children of non-citizen Chinese immigrants, only served one term, and wikipedia claims that one factor in his not being sent back to Washington for a second term related to his having views on the rights of Chinese-Americans that were more expansive than those of most California voters.

Chris said,

July 26, 2018 @ 6:04 pm

I agree with outeast and JWB about the meaning suggested by the discussion of Chinese immigrants. However, as a linguistic matter, I think my interpretation "who belong to.." as providing an example of "foreigners, aliens" rather than defining "foreigners" is correct.

Brett Dunbar said,

July 26, 2018 @ 8:46 pm

The text of the amendment excludes people born in the US who are not subject to US law. That is essentially diplomatic staff and associated persons with diplomatic immunity.

There is historical precedent for this kind of extraterritorial privileges being much more widely applied, such as with the unequal treaties with China. If the US were obliged by treaty to grant resident foreign citizens similar extraterritorial privileges then the children of those foreign nationals subject only to their own courts not those of the USA would not automatically be American citizens. As the US has never found itself so weak as to be subject to such humiliating treaty provisions that is an empty set, nonetheless the amendment allows for it.

Chris said,

July 26, 2018 @ 10:03 pm

@Brett Dunbar

"The text of the amendment excludes people born in the US who are not subject to US law."

It's slightly more complicated than that. The class of people who are not subject to US law can be defined by Congress–for example, via treaties–as well as the degree of lack of subjugation. That is the point of the Globe discussion about Native Americans. In that case, the US was not "humiliated" by its treaties with NA tribes, but rather chose to extend to them certain privileges, which then happened to negate their birthright citizenship. The case of NA tribes muddies the waters for our current politics as, despite being considered not subject to US jurisdiction, NA tribes did not have "diplomatic immunity" at the time the 14th Amendment was passed.

If we take the Globe discussion as a serious guide to interpreting the Amendment, the situation seems to me to be further complicated by Howard's use of "foreigners, aliens…" to describe people with diplomatic immunity. After all, what is the point of the Amendment's definition of citizenship? Was the Amendment designed to be a silly tit-for-tat where the US says, "All right, if we can't arrest you as a child, you can't be a citizen as an adult," or was it designed to exclude people who are not members of the community? Why did Howard describe the excluded class as "foreigners" rather than "the privileged" or "diplomats" or something more precise?

The Globe's discussion of the Chinese clearly indicates that the children of foreign-born migrants were to be considered citizens, but the discussion of NA tribes' lack of tax burden shows that they were considering people who were participating in the community fully. Thus, Howard's confusing language conflating foreignness with diplomatic immunity.

Gwen Katz said,

July 27, 2018 @ 1:48 am

The natural meaning to me is to have "who belong to the families.." modifying "aliens" and have the entire phrase "aliens who belong to the families…" in apposition to "foreigners."

But in this case I think trying to tease out the grammatical structure he intended to use is less useful than just looking at what information he did and didn't choose to include. If he meant all children of foreigners, I'd expect him to either not give examples at all or to list several examples (eg, "people whose families are on vacation," "people whose parents are exchange students," etc), or at least to say "such as" or "for example" to indicate that he means to include other groups not mentioned as well.

Giving one example of a specific type of foreigner (without specifically indicating that it's just an example and you mean everyone else too) only makes sense to me if you specifically wanted to point out that type of person because they were different from all the other foreigners in some relevant way.

But it's an academic exercise either way, or at least it should be, because our laws should really be decided by our current circumstances, not by whether or not a 19th-century congressman meant to say "or".

dw said,

July 27, 2018 @ 3:59 am

Would a child born to, say, British-born immigrants have had British citizenship?

Chester Arthur, son of an Irish-born father, became President of the United States. His father did become a US citizen, but not until after Chester’s birth.

Rodger C said,

July 27, 2018 @ 8:40 am

Andrew Jackson was born to very recent Irish immigrants; there were rumors among his political enemies that he was actually born on board ship and hence not a native-born citizen.

Stacey Harris said,

July 27, 2018 @ 5:34 pm

Just on a reading of the Globe transcript, my grammatical interpretation is different from any I've seen expressed above:

I see two appositions, one contained in another:

…persons born in the United States [(1) who are [(1) foreigners, (2) aliens], (2) who are born to the families of embassadors…]

That is to say: In the larger apposition, "who are born to the famiiles of embassadors…" is apposite to "who are foreigners, aliens"; the small apposition has "aliens" apposite to "foreigners".

That, at least, is the way I would speak those words; it seems the natural expression to me.

Paul Kay said,

July 27, 2018 @ 7:12 pm

I think all one needs to do to make the original, not only grammatical and idiomatic, but also in keeping with the other indications of the original intent (as noted by outeast, for example) is to imagine that the second comma would be removed by an editor today as erroneously setting off a restrictive relative clause. (I think this is essentially Gwen Katz's idea.) Removing that comma we have, "This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers." The appositive noun phrase "aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers" clarifies how somebody can be born in the U.S. but nevertheless a foreigner not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. Putting a comma before a restrictive relative clause seems to me like an easy mistake to make; for that matter. I don't know anything about punctuational practice in the mid-19th century. Maybe punctuation rules were looser then.

I certainly agree that the insertion of [or] is unjustified. There is, however, a reading with the suspicious "or" included that doesn't rely on the 3-item conjunction "foreigners, aliens, or who…ministers", but rather a two-item conjunction of relative clauses: ""This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States [who are foreigners, aliens] or [who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.]" I don't propose this reading. It seems unlikely for several reasons that don't need rehearsing; I have no idea whether it it has ever been proposed.

Neal Goldfarb said,

July 28, 2018 @ 11:43 am

Having read Paul Kay's comment, I think that he and Gwen Katz are right. When I initially read Gwen's comment, I was in skimming mode and didn't really focus on what she was saying. But knowing who Paul is, I read his comment more carefully. (Name-recognition has its advantages.)

I'm going to add another update to the post, to include the reading that David, Gwen, and Paul have pointed out.

cameron said,

July 28, 2018 @ 6:25 pm

I think Gwen Katz and Paul Kay were in agreement with my earlier comment: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=39284#comment-1553359

But I stressed also that the phrase in question is in apposition to the noun phrase "persons born in the US who are foreigners".

Paul Kay said,

July 28, 2018 @ 11:02 pm

@Cameron. Right. I should have caught that.

Neal Goldfarb said,

July 30, 2018 @ 2:05 am

@cameron: "I think Gwen Katz and Paul Kay were in agreement with my earlier comment"

I've revised the update at the end of the post, to credit cameron and to quote from his comment.

I really hope that I won't have to make any more updates.

dainichi said,

July 30, 2018 @ 10:09 pm

Sorry, I still don't quite get it. Assuming that the parse in the update is the intended one, why

> aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

instead of, say,

> newborns who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers

? Howard is using "alien" to specify who has citizenship, which seems circular. Or does "alien" refer to something other than citizenship here? Are there any non-aliens who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers, who therefore are citizens?

Ran Ari-Gur said,

July 31, 2018 @ 12:48 am

I think you're mistaken about this part:

> This structure would generate the interpretation that Anton advocates, but with no conjunction between foreigners and aliens, it is, as I’ve just said, quite unnatural. Although coordination without a conjunction can work sometimes—it’s called asyndetic coordination—I don’t think this is one of those times. Among other factors, asyndetic coordination strikes me as more of a rhetorical device than a syntactic workhorse. So this interpretation doesn’t really works unless another “[or]” is inserted, this time between foreigners and aliens.

Such multiple-level coordination (e.g. "foo {bar, baz}, or bip" meaning "foo bar or foo baz or bip") is actually not that uncommon, including in edited prose, and native speakers tend not to blink at it. Neal Whitman has catalogued scores of real-world examples on his blog: https://literalminded.wordpress.com/2008/05/16/my-multiple-level-coordination-collection/