Shimao, graphic arts, and long distance connections, part 2

Intercultural connections imply crosscultural communications.

In my estimation, Shimao is the most important archeological site in the EEAH (Extended East Asian Heartland) from B.C. times, with enormous implications for the origins of Sinitic civilization. Shimao is a recently discovered archeological site, brought to light roughly a dozen years ago, but still very much under excavation. Its coordinates are 38.5657°N 110.3252°E, which put it on the mid-eastern edge of the Ordos Desert that lies within the great, rectangular bend of the Yellow River called the Ordos Loop in English or Hétào 河套 ("Yellow River Sheath") in Chinese. I often think of the Ordos as the omphalos of the EEAH, ecologically a part of the Eastern Gobi desert steppe that has been lassoed ("lasso" is another meaning of tào 套) into the cultural orbit of the Yellow River Valley, which is the center of the East Asian Heartland (EAH) proper.

For the concept of East Asian Heartland (EAH) and Extended East Asian Heartland (EEAH), see Victor H. Mair, "The North(west)ern Peoples and the Recurrent Origins of the 'Chinese' State", in Joshua A. Fogel, The Teleology of the Modern Nation-State: Japan and China (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), pp. 46-84.

Read the rest of this entry »

Plagiarism: Double (and triple and quadruple) standards

My reaction to the current controversy over Claudine Gay's alleged plagiarisms is to observe again that the relevant policies are a tangled and incoherent mess. I first wrote about this back in 2006 — and as it happens, that post compared the work of a different university president with the treatment of a Harvard undergraduate accused of plagiarism:

We tell kids that plagiarism is wrong, but we tell them that a lot of things are wrong that they see successful and respected people doing every day. […] In fact, anyone who pays attention knows that in some cases, like political speeches and celebrity memoirs, it's normal and expected to pass the work of others off as your own.

Here's an example that cuts close to the academic bone. A couple of decades ago, X was a graduate student at Y University, a school that regularly appears in U.S. News and World Report's listing of the top 50 American universities, and not at the bottom of the list either. The school's president, Dr. Z, had a nationally syndicated column. It ran under his byline, but X helped pay her way through school by writing it. I don't mean that she edited it, or did research for it, or drafted it. She came up with the ideas, did whatever research was required, and wrote it exactly as it ran. Dr. Z approved it for publication, or at least was given the opportunity to do so, but he never changed anything. (Or so X told me, and I believe her.)

I'm sure that Y University had a policy against plagiarism, like all similar institutions. It no doubt defined plagiarism in the usual way, as "the act of using the ideas or work of another person or persons as if they were one's own, without giving proper credit to the source" or something of the sort. This definition obviously applies to hiring someone to research and write your papers for you, just as much as it applies to copying passages from a book or cutting and pasting from an online source. (And writing-for-hire is hard to detect unless the hireling squeals. I've heard of one case that was uncovered because the hireling plagiarized a term paper from online sources, and when the copying was detected by the usual means, the accused student tried to absolve herself on the grounds that the guilty party was really the person that she had hired. "I hope you throw the book at the lousy cheater", she is apocryphally supposed to have exclaimed.) In any event, if Ms. X had been caught hiring someone to write her graduate-school term papers for her, she would surely have been unceremoniously dropped from the program.

Read the rest of this entry »

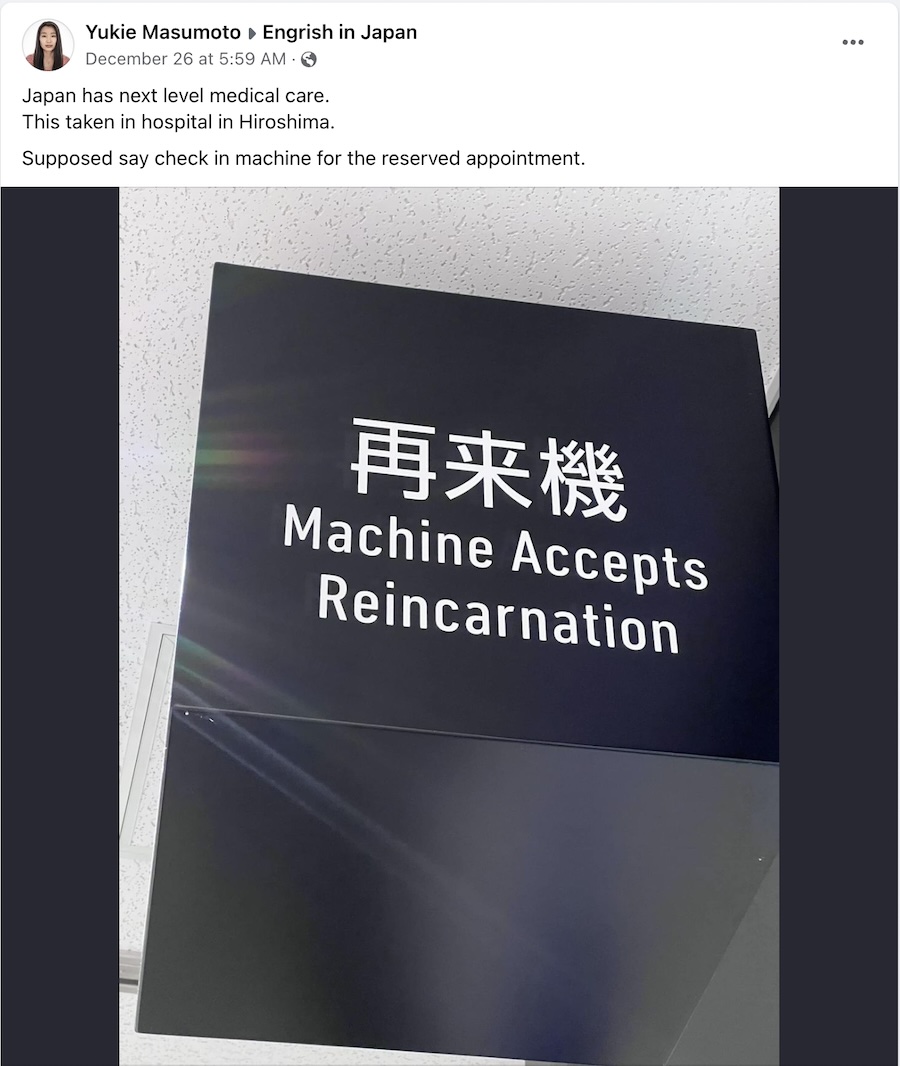

Declining English in the Land of the Rising Sun

Shocking (to me) news:

"Japan’s English Proficiency Continues to Drop Among Non-English-Speaking Countries"

nippon.com (Dec 4, 2023)

A survey found that Japan currently ranks eighty-seventh out of 113 non-English-speaking countries and regions for English language abilities. This is a fall of seven places from last year and relatively low among Asian countries.

I'm dubious that English proficiency would be so low in Japan, which overall has such a high level of education and which has such a large number of loanwords from English. Is this a case of lies, damned lies and [polling-generated] statistics"?

Read the rest of this entry »

Talking animals

Those whale vowels are on my to-blog list. But for now, please remember that talking animals can be dangerous — at least, this evening:

"Talking animals: Miracle or curse?", 12/24/2004

"Watch out for those talking animals tonight", 12/24/2013

"Trigger warning: Talking animals", 12/24/2015

Thou shalt not mention "Egg Fried Rice" in the PRC

Subtitle: "Thank you, Egg Fried Rice"

You may think that nothing could be more innocuous than mundane egg-fried rice. Not so in post-Mao China. As background for the story I'm about to tell, you need to know that eggs were a rarity in the PRC during the days of Mao, and especially during the Korean War (1950-53), in which China was pitted against the USA and the UN.

So you know the vocabulary, it is "dàn chǎo fàn 蛋炒饭" ("egg fried rice").

Egg Fried Rice

What is said to have killed Mao Zedong’s oldest son, Mao Anying. The younger Mao, who had studied abroad in Russia, volunteered to fight in the Korean War and was assigned to be Peng Dehuai*’s Russian translator. According to legend, Mao Anying cooked fried rice with eggs in the daytime, against military regulation. The eggs were a rare delicacy at the time and had been just been sent to Peng Dehuai from Kim Il-sung. Spotting the smoke from the fire, an American plane dropped napalm on the site. Unable to escape, Mao perished in the flames.

Regardless of the truth of the story, Mao Anying did in fact die in 1950 when his camp in a Korean cave was napalmed.

Read the rest of this entry »

St. Victor (the Abbey): the language of plans, elevations, sections, and perspectives

Before reading the following article, I didn't even know there was a St. Victor, let alone an Abbey of St. Victor that was established in 1108 near Notre-Dame Cathedral, at the beginning of the "Twelfth-Century Renaissance", in Paris.

The surprising history of architectural drawing in the West

Karl Kinsella, Aeon (12/21/23)

Here's a quick tutorial from the National Design Academy on the architectural language alluded to in the title of this post:

What’s the Difference Between a Plan, Elevation and a Section?

This brief guide uses an ingenious way of looking at an orange from four viewpoints to explain these four main terms of architectural language. Armed with this fundamental knowledge, let us now join Karl Kinsella in learning about the architectural drawings of the Abbey of St. Victor and other Western religious edifices. I should preface my overview of Kinsella's article by pointing out the it is accompanied by seven extraordinary period illustrations.

Kinsella begins with Vitruvius' De architectura in the 1st c. BC and moves quickly to the 15th c. when "the artist and architect Leon Battista Alberti, in his brief mention of architectural drawings, assumes that they are done only by architects." Then comes the real story:

Read the rest of this entry »

Opacity of the week: all pills $11.95

That's the sign on the door of a gas station that I saw in Media, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. It had pictures of four different packages of pills, but the lettering on them was so blurred that I couldn't see what types or brands of pills they were.

ALL PILLS

$11.95

That was the only sign on the door, and it was very prominent: right in the center of the door as you entered. As I stepped inside the store, I was wondering mightily: why are they selling you pills when they don't tell you what kind of pills they are?

After going inside and paying for my gas, I asked the two female attendants, who were all dressed up in holiday attire, what kind of pills they were, both of them said in unison, "male enhancement", as though they had rehearsed the answer hundreds of times. I was embarrassed and so were they, so I got out as fast as I could.

Read the rest of this entry »

Tocharian Bilingualism and Language Death in the Old Turkic Context

Sino-Platonic Papers is pleased to announce the publication of its three-hundred-and-thirty-seventh issue:

“Tocharian Bilingualism, Language Shift, and Language Death in the Old Turkic Context,” by Hakan Aydemir.

ABSTRACT

The death of a language is a sad and dramatic event. It is, however, a fact that many languages died out in the past and are now dying out as well. However, although we often know the time and causes of present or recent language deaths and have a relatively large amount of information about them, we often do not know the time and causes of past language deaths, or our knowledge of these processes is very limited. In other words, the very limited written sources or linguistic material make it very difficult to study “language shift” or “language death” phenomena in historical periods.

Read the rest of this entry »

AI wins literary prize?

According to Justinas Vainilavičius, "AI-generated science fiction novel wins literary prize in China", Cybernews 12/20/2023:

It only took three hours for Shen Yang, a professor at the Beijing-based university’s School of Journalism and Communication, to generate the award-winning admission.

The Chinese-language work, entitled The Land of Machine Memories, won second prize at the 5th Jiangsu Popular Science and Science Fiction Competition.

According to Chinese media reports, the draft of over 40,000 characters was generated based on 66 prompts, suggesting a “Kafkaesque” writing style.

Shen was encouraged to submit an excerpt of nearly 6000 characters for the competition by one of the judges, the Wuhan Evening News reported.

The judge, Fu Changyi, told the paper that he did not inform the other judges of the true authorship of the text because he wanted to see their judgment.

Read the rest of this entry »

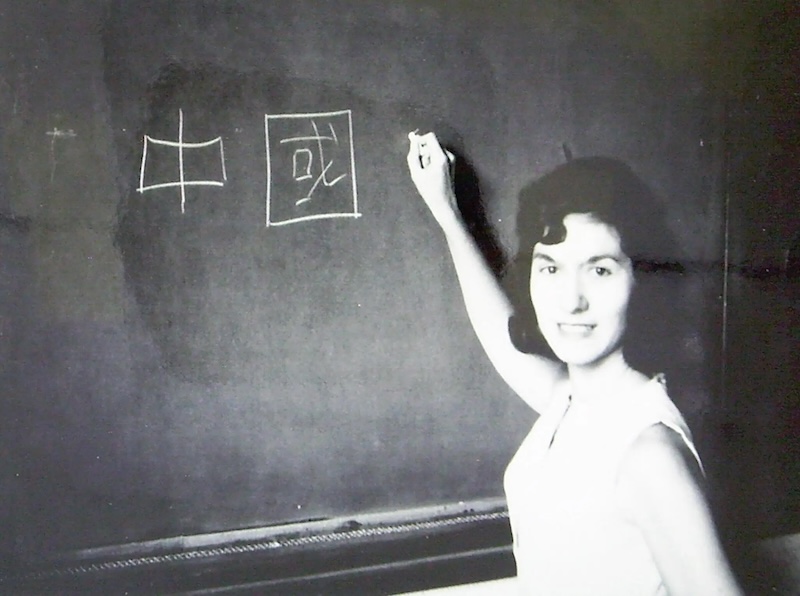

Decryption of a difficult script

Photograph accompanying a New York Times article, with the following caption: "Merle Goldman explaining the Chinese characters for the word China":

(source)

Read the rest of this entry »