The transformative power of translation

« previous post | next post »

"Not Lost In Translation: How Barbarian Books Laid the Foundation for Japan’s Industrial Revolution", by Alex Tabarrok, Marginal Revolution (July 22, 2024)

I am grateful to Alex Tabarrok and his colleague Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution University of George Mason University's Mercatus Center for introducing me to what is one of the most mind-boggling/blowing papers I have read in the last decade.

First, here is Tabarrok's introduction, and that will be followed by selections from the revolutionary paper to which I am referring.

Japan’s growth miracle after World War II is well known but that was Japan’s second miracle. The first was perhaps even more miraculous. At the end of the 19th century, under the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed itself almost overnight from a peasant economy to an industrial powerhouse.

After centuries of resisting economic and social change, Japan transformed from a relatively poor, predominantly agricultural economy specialized in the exports of unprocessed, primary products to an economy specialized in the export of manufactures in under fifteen years.

In a remarkable new paper, Juhász, Sakabe, and Weinstein show how the key to this transformation was a massive effort to translate and codify technical information in the Japanese language. This state-led initiative made cutting-edge industrial knowledge accessible to Japanese entrepreneurs and workers in a way that was unparalleled among non-Western countries at the time.

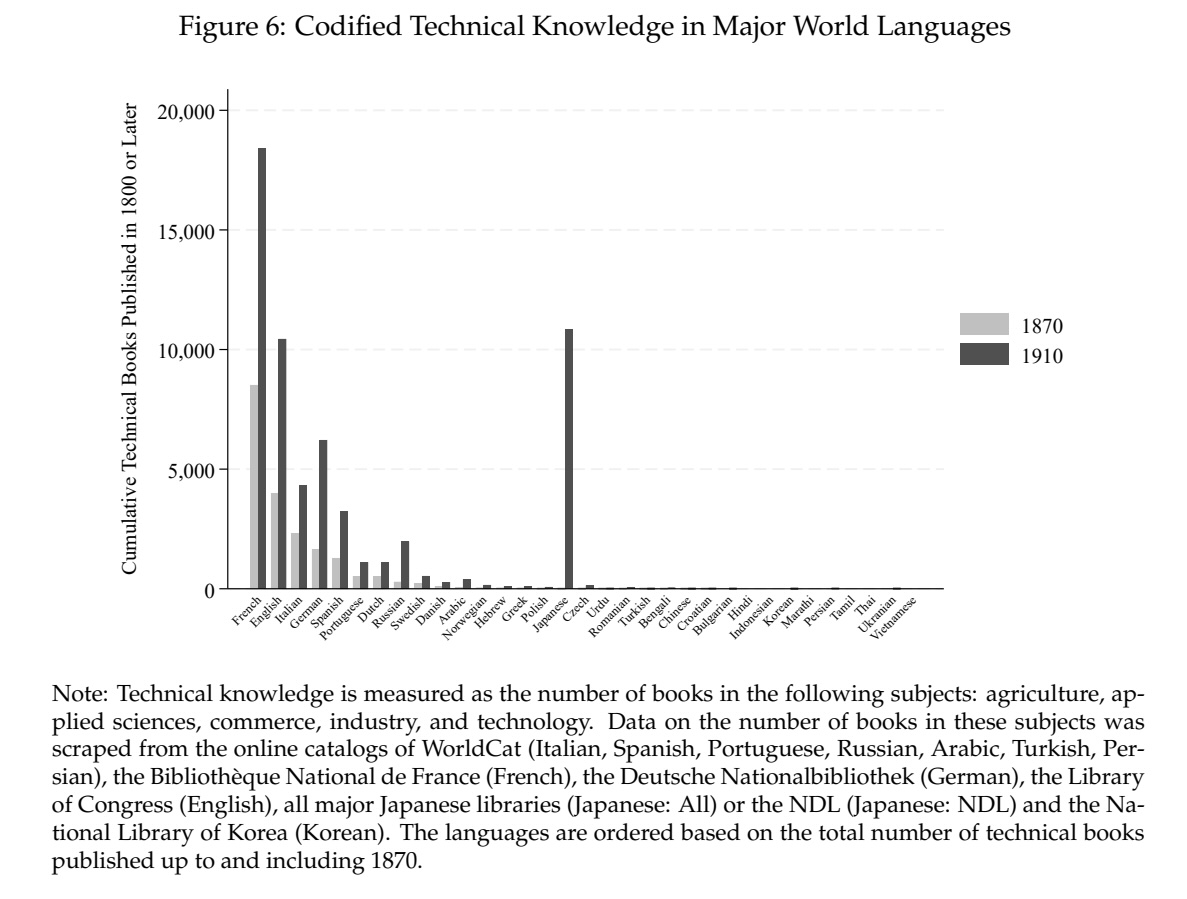

Here’s an amazing graph which tells much of the story. In both 1870 and 1910 most of the technical knowledge of the world is in French, English, Italian and German but look at what happens in Japan–basically no technical books in 1870 to on par with English in 1910. Moreover, no other country did this.

[Click to embiggen for easy reading]

Translating a technical document today is much easier than in the past because the words already exist. Translating technical documents in the late 19th century, however, required the creation and standardization of entirely new words.

…the Institute of Barbarian Books (Bansho Torishirabesho)…was tasked with developing English-Japanese dictionaries to facilitate technical translations. This project was the first step in what would become a massive government effort to codify and absorb Western science. Linguists and lexicographers have written extensively on the difficulty of scientific translation, which explains why little codification of knowledge happened in languages other than English and its close cognates: French and German (c.f. Kokawa et al. 1994; Lippert 2001; Clark 2009). The linguistic problem was two-fold. First, no words existed in Japanese for canonical Industrial Revolution products such as the railroad, steam engine, or telegraph, and using phonetic representations of all untranslatable jargon in a technical book resulted in transliteration of the text, not translation. Second, translations needed to be standardized so that all translators would translate a given foreign word into the same Japanese one.

Solving these two problems became one of the Institute’s main objectives.

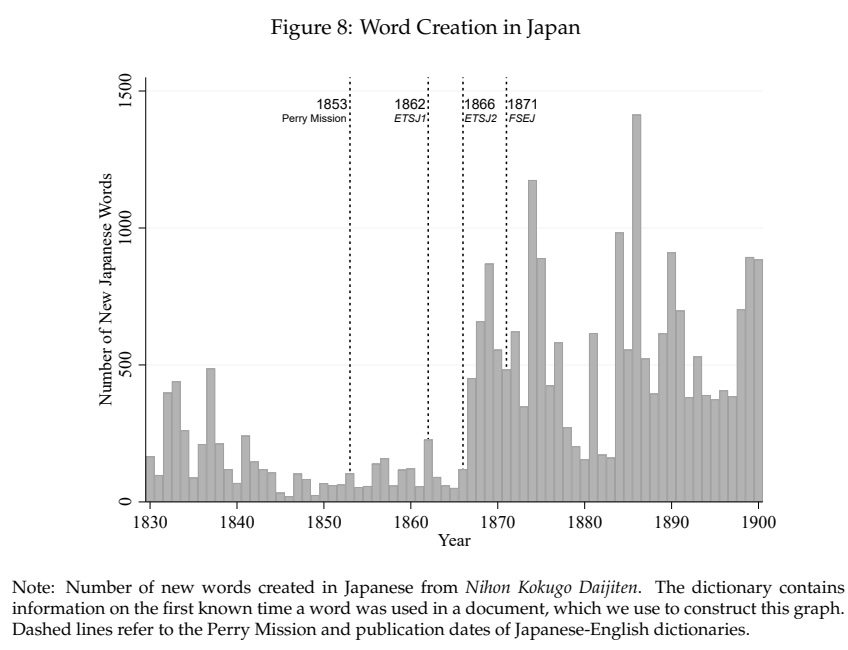

Here’s a graph showing the creation of new words in Japan by year. You can see the explosion in new words in the late 19th century. Note that this happened well after the Perry Mission. The words didn’t simply evolve, the authors argue new words were created as a form of industrial policy.

[Click to embiggen for easy reading]

By the way, AstralCodexTen points us to an interesting biography of a translator at the time who works on economics books:

[Fukuzawa Yukichi {1835-1901}] makes great progress on a number of translations. Among them is the first Western economics book translated into Japanese. In the course of this work, he encounters difficulties with the concept of “competition.” He decides to coin a new Japanese word, kyoso, derived from the words for “race and fight.”* His patron, a Confucian, is unimpressed with this translation. He suggests other renderings. Why not “love of the nation shown in connection with trade”? Or “open generosity from a merchant in times of national stress”? But Fukuzawa insists on kyoso, and now the word is the first result on Google Translate.

[*VHM: I think this explanation may be confusing to some readers. Fukuzawa's neologism for "competition" is kyōsō 競争, which may also mean "rivalry, contest, emulation, tournament, strife". 競 by itself may mean "compete" and 争 by itself may mean "contest".]

There is a lot more in this paper. In particular, showing how the translation of documents lead to productivity growth on an industry by industry basis and a demonstration of the importance of this mechanism for economic growth across the world.

The bottom line for me is this: What caused the industrial revolution is a perennial question–was it coal, freedom, literacy?–but this is the first paper which gives what I think is a truly compelling answer for one particular case. Japan’s rapid industrialization under the Meiji Restoration was driven by its unprecedented effort to translate, codify, and disseminate Western technical knowledge in the Japanese language.

If you have time, many of the comments that follow the post are illuminating in their own right and worth delving into.

Now, on to the original paper:

"CODIFICATION, TECHNOLOGY ABSORPTION, AND THE GLOBALIZATION OF THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION", by Réka Juhász, Shogo Sakabe and David Weinstein, NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH Working Paper 32667 (July, 2024)

Abstract

This paper studies technology absorption worldwide in the late nineteenth century. We construct several novel datasets to test the idea that the codification of technical knowledge in the vernacular was necessary for countries to absorb the technologies of the Industrial Revolution. We find that comparative advantage shifted to industries that could benefit from patents only in countries and colonies that had access to codified technical knowledge but not in other regions. Using the rapid and unprecedented codification of technical knowledge in Meiji Japan as a natural experiment, we show that this pattern appeared in Japan only after the Japanese government codified as much technical knowledge as what was available in Germany in 1870. Our findings shed new light on the frictions associated with technology diffusion and offer a novel take on why Meiji Japan was unique among non-Western countries in successfully industrializing during the first wave of globalization.

Telling prefatory quotation

“At present, the learning of China and Japan is not sufficient; it must be supplemented and made complete by inclusion of the learning of the entire world… I would like to see all persons in the realm thoroughly familiar with the enemy’s conditions, something that can best be achieved by allowing them to read barbarian books as they read their own language. There is no better way to enable them to do this than by publishing [a] dictionary.”

Shozan Sakuma (1811-1864), 1858, quoted in Hirakawa (2007, p. 442, emphasis added)

Hirakawa, S. (2007). Japan’s turn to the West. In J. W. Hall, M. B. Jansen, M. Kanai, and D. Twitchett (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Japan: The Nineteenth Century, Volume 5, pp. 432–498. New York: Cambridge University Press.

N.B.: Already in the middle of the 19th century, Japanese were thinking of an East Asian co-prosperity condominium with China.

As to why the trajectory of scientific change was so radically different in Japan from what it was elsewhere outside of Europe, the authors have their own hypotheses and draw their own conclusions, which are basically centered on economic realities and grounded in "technical literacy / knowledge", i.e., "the codification of engineering, commercial, and industrial practices"

Fair enough, but neither this team of brilliant analysts nor any other scholars I know of attribute Japan's meteoric rise to the fact that, despite their being sealed off from the rest of the world until Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794-1858) with his Black Ships forced the Japanese empire to open its ports and gates (1852-54), their possession of a flexible script (phonetic kana plus morphosyllabic kanji) was operative. In my estimation such a writing system would have played a significant role in their lexicographic borrowing and epistemological foundations.

Selected readings

William C. Hannas, Asia's Orthographic Dilemma (Honolulu, Hawai'i: University of Hawai'i Press, 1997).

William C. Hannas, The writing on the wall: How Asian orthography curbs creativity (Philadelphia, PA: University of Philadelphia Press, 2003).

[Thanks to Ben Benzon]

Ross King said,

July 25, 2024 @ 3:08 pm

Interesting. Speaking as a Koreanist, I have to wonder to what extent Korea and Korean then subsequently enjoyed the 'latecomer advantage', insofar as all those neologisms created in Japan were easily downloaded lock, stock, and barrel (to use a technological metaphor) into Korean within a generation or so, the only change being in pronunciation of the relevant sinographs (pronounced of course in their Sino-Korean readings). But since they were under the Japanese colonial thumb until 1945 and then had to suffer through division and the Korean War, the Koreans couldn't capitalize on this 'latecomer advantage' until later (if, in fact, any connection can be drawn between the 'Miracle on the River Han' and Korea's downloading of a ready-made sinographic lexicon for all things technological).

Neil Kubler said,

July 25, 2024 @ 4:33 pm

Thousands upon thousands of these translations of European language technical, scientific, sociological, and humanistic terms were created by Japanese translators, in almost all cases making use of the modern Japanese pronunciations of Chinese morphemes/syllables borrowed from Chinese over 1,000 years earlier along with the Chinese characters used to represent them in writing. Piggy-backing on Ross King's comment, not only did Koreans bring these terms (written with the same Chinese characters but pronounced in Korean) into their language "lock, stock, and barrel," but so did the Chinese, primarily via the many thousands of Chinese students who studied in Japan during this same period (Japan being a lot closer to China than Europe). Most of these terms were then introduced into original writings in Chinese, where they took root and became high-frequency terms in the modern Chinese language, with the result that most native Chinese readers today are totally unaware that terms like 經濟 'economics', 物理 'physics', 國際 'international', 法律 'law', 雜誌 'magazine', 系統 'system', and 自由 'freedom' are from Japan rather than being Chinese creations.

Victor Mair said,

July 25, 2024 @ 5:31 pm

Thank you so much, Ross and Neil, for your cogent, consequential comments.

Within a day or two, I will put up a guest post by Nathan Hopson of a detailed case study of one of these words, viz., that for "protein".

Some of these terms were what I call "round-trip words", e.g., that for "economics". They came to Japan from China in premodern times with one, traditional meaning, had a new, Western-oriented meaning attached to them, and were sent back to China in that new guise.

"Japanese borrowings and reborrowings" (4/20/24) — see especially the bibliographical entries

See VHM, "East Asian Round-Trip Words", Sino-Platonic Papers, 34 (October, 1992), 5-13.

e.g., on p. 9, 經濟

Middle Sinitic kieng-tsiei ("rule [the realm] and succor [the people]"

–>

Japanese keizai ("economics")

–>

Modern Standard Mandarin jīngjì ("economics; economical")

KWillets said,

July 26, 2024 @ 1:05 am

Did 경제 obtain the modern meaning with the older Chinese pronunciation?

Coby said,

July 26, 2024 @ 11:22 am

"Round-trip words" exist in Modern Greek as well, except that (1) suffixes are sometimes modified (so that, for example, holocaust is ολοκαύτωμα) and (2) in Greek-Latin blends the Latin element is replaced by a Greek one, so that automobile is αυτοκίνητο, sociology is κοινωνιολογία, etc.

John Whitman said,

July 26, 2024 @ 2:48 pm

This is a very rich paper. Juhász et al. miss one important thing: the significant continuity in government support for technical translation from Western languages spanning Edo and Meiji. The Edo bakufu established the Bansho wage goyо̄ 蛮書和解御用 in 1811, tasked with translating Western texts, at first primarily Dutch, as the first cadre of translators were Rangaku 'Dutch learning' specialists, but later expanded to other Western languages. The office was placed in the Tenmonkata 天文方, the institute for calendrical/astronomical research as well as dicta on official weights and measurements. In 1856 this was split off and expanded to become the Bansho shirabesho 蕃書調所 'Institute for investigating barbarian books' (at first named the Yо̄gakusho 洋学所 'Institute for Western learning'), which took on a teaching as well as translating function.

Juhász et al's figure on p. 21 (Fig. 8 Word Creation in Japan) actually captures this burst of translation activity: the total of just under 500 new words in 1837 is not matched until 1868, and then only 8 more times before 1884.

Pre-Meiji technical translation focused on (1) military technology) and (2) medicine. This reflected both bakufu and han 藩 interests, but it was probably fairly parallel tot he predominance technical translation in Europe as well at the outset of the industrial revolution.

applied

sciences, industry, technology

Peter Kornicki said,

July 27, 2024 @ 9:42 am

In the introduction Alex Tabarrok states:

'At the end of the 19th century, under the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed itself almost overnight from a peasant economy to an industrial powerhouse.' I think Tabarrok means EITHER after the Meiji Restoration (of 1868) OR under the Meiji government, but to describe the Japanese economy even in 1800 as a peasant economy is seriously problematic, as Thomas Smith showed long ago. Also, the significance of pre-Meiji translation has been seriously underestimated: it focused on botany, medicine and other sciences and only turned to military technology around the middle of the 19th century, but the important point is that the creation of a vernacular scientific vocabulary began in the 18th century and Japanese intellectuals were well accustomed to the idea of deriving knowledge from translation well before the Meiji period.

Tom said,

July 27, 2024 @ 5:29 pm

As is partially illustrated by the biography posted on ACX blog, the social structure of the Edo period facilitated translation activity. There was a class of people who had the free time and financial security to pursue learning languages. As well, Neoconfucianism identified the samurai with scholarship, which probably introduced an ideological support for study that would have been absent in other times/places.

In case anyone doesn't know what to do with a Saturday night, the Kurosawa film Red Beard touches on Dutch medical translations.