Big, open, high, ?

« previous post | next post »

Paul Eprile has a new translation of Jean Giono's 1951 novel Les Grands Chemins, under the title The Open Road. The publisher's blurb describes it this way:

The south of France, 1950: A solitary vagabond walks through the villages, towns, valleys, and foothills of the region between northern Provence and the Alps. He picks up work along the way and spends the winter as the custodian of a walnut-oil mill. He also picks up a problematic companion: a cardsharp and con man, whom he calls “the Artist.” The action moves from place to place, and episode to episode, in truly picaresque fashion. Everything is told in the first person, present tense, by the vagabond narrator, who goes unnamed. He himself is a curious combination of qualities—poetic, resentful, cynical, compassionate, flirtatious, and self-absorbed.

Reading this, I wondered whether this novel might have helped inspire Jack Kerouac's 1957 novel On the Road — Kerouac spoke French until the age of six, and wrote in French as well as English throughout his life, so it's plausible that he read Giono. But Les Grands Chemins was first published in May of 1951, and Wikipedia tells us that

The idea for On the Road, Kerouac's second novel, was formed during the late 1940s in a series of notebooks, and then typed out on a continuous reel of paper during three weeks in April 1951.

Anyhow, this is Language Log and not Mid-20th-Century Counter-Culture Log, and the other thing that struck me about Giono's book was a point about lexicons, namely the evolution of semi-compositional fixed phrases like grand chemin and open road. In English we also have highway, high street, high road, main street, main road. And there's a network of partial correspondences, like the fact that the French for "highwayman" is "voleur de grand chemin" = "big road thief".

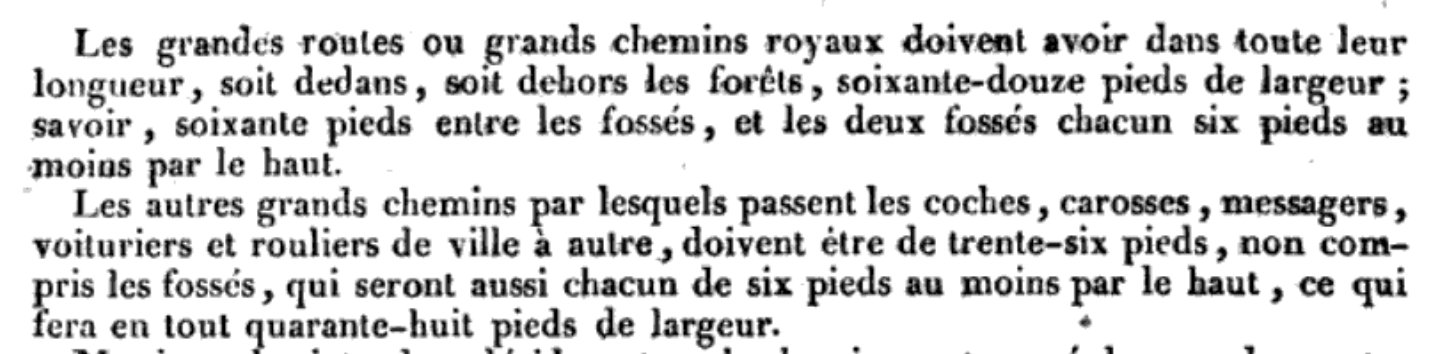

At some point a few hundred years ago, the French phrase "grands chemins" also acquired a technical (and perhaps even legal) layer of meaning. From page 26 of volume 2 of the 1807 edition of Recueil Polytechnique Des Ponts Et Chaussées, Bois et Forêts, Chemins, Routes, Canaux de navigation, Ports maritimes, Exploitation des mines, Desséchement des marais, Agriculture, Manufactures, Arts mécaniques, Architecture géométrique et hydraulique, et constructions civiles en général:

Royal highways ("great royal routes or roads") must have throughout their length, whether inside or outside of forests, seventy two feet of width; that is, sixty feet between the ditches, and two ditches each at least six feet at the top.

The other highways, by which travel coaches, messengers and drivers, must be thirty six feet wide, not including the ditches, which will be also at least six feet at the top, which makes forty eight feet in width.

I haven't seen similar technical particularization for English "open road", but of course that phrase has accrued layers of metaphorical connotation. The OED glosses it (with citations back to 1656) as "A country road, or a main road outside the urban areas, where unimpeded driving is possible. In figurative contexts: freedom of movement."

A typical figurative usage is Walt Whitman's "Song of the Open Road":

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

Henceforth I ask not good-fortune, I myself am good-fortune,

Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone no more, need nothing,

Done with indoor complaints, libraries, querulous criticisms,

Strong and content I travel the open road.

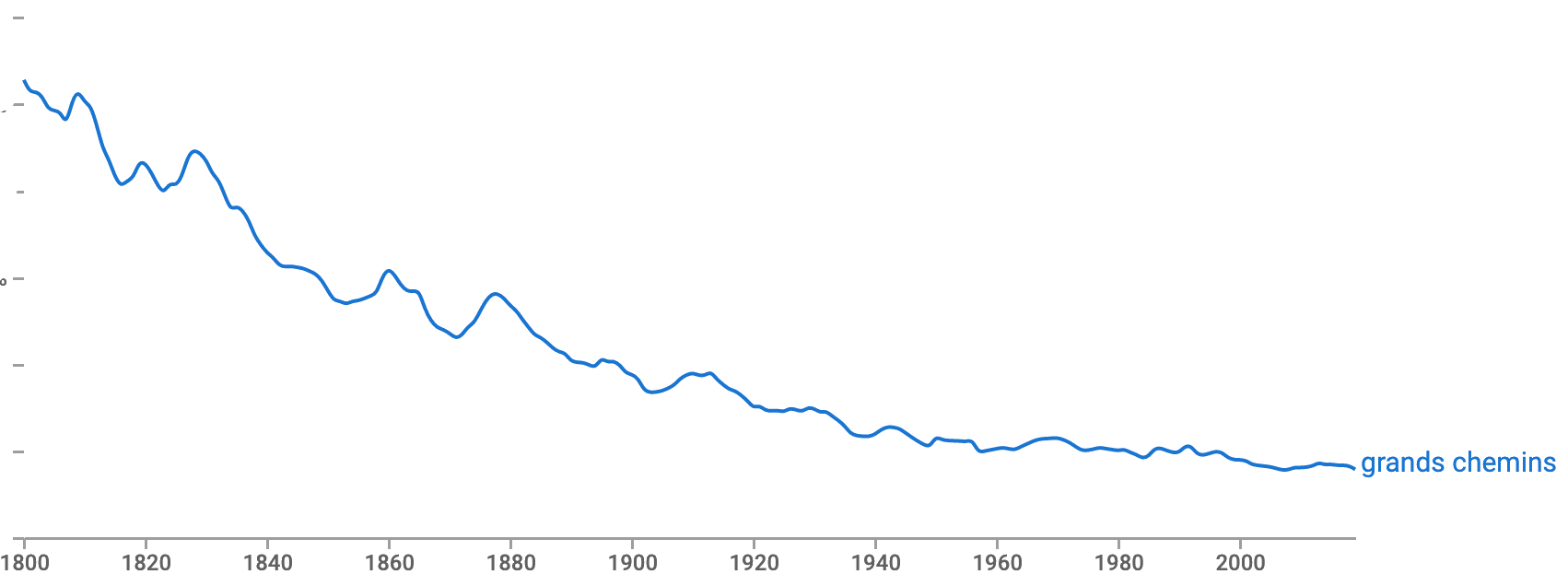

Google Ngrams tells us that the frequency of the phrase "grands chemins" has been declining for the past couple of centuries:

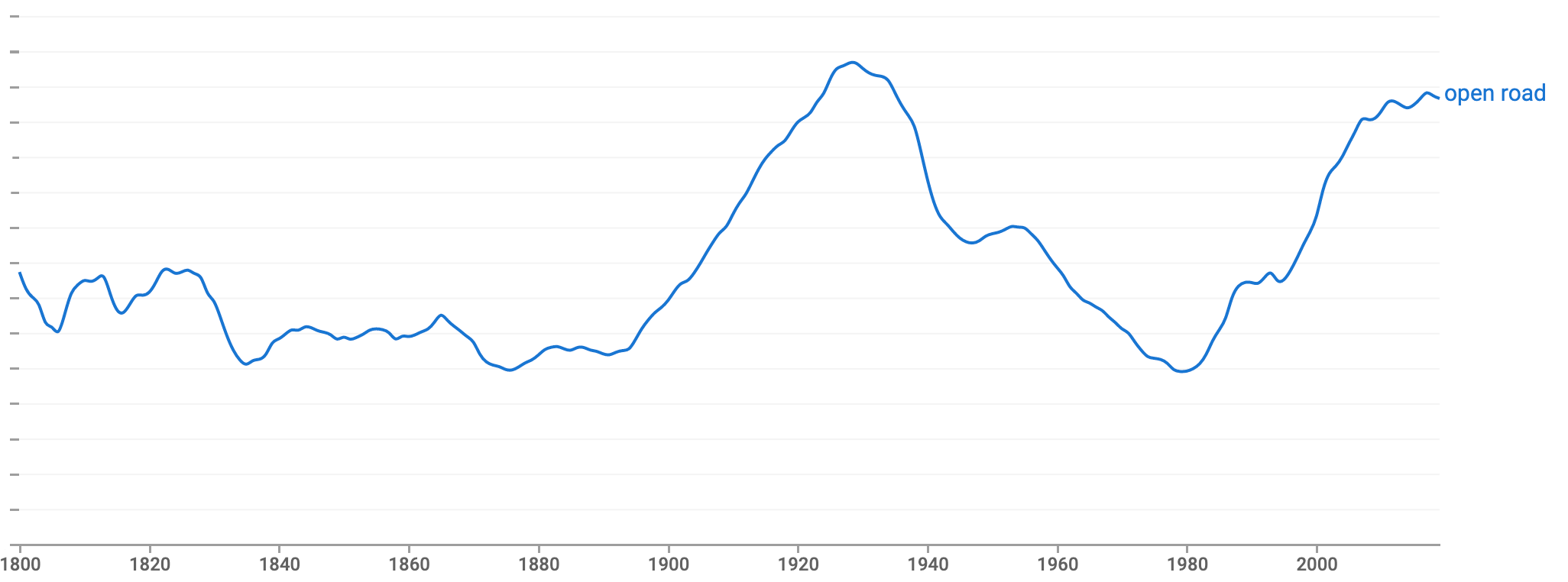

But the history of "open road" is different:

There are lots of related questions, but an obvious one is what modifiers have evolved across languages for which culturally-relevant particularizations of road-words.

Philip Taylor said,

November 7, 2021 @ 9:09 am

Just a side-note that as well as having highway, high street, main street in English, we also have fore-street, seemingly ubiquitous throughout Cornwall.

Will Thomas said,

November 7, 2021 @ 9:25 am

I thought 'high street' was English. I don't remember hearing it used in the US–at least the southeastern US.

[(myl) I agree that it's a UK thing — but I've been told that they speak English there too…]

Vance Koven said,

November 7, 2021 @ 10:32 am

You'll find plenty of High Streets in New England cities and towns. Fore Streets too.

Bob Ladd said,

November 7, 2021 @ 10:37 am

Off topic, but I thought the metric system came in with the French Revolution in 1789 – but here they are, nearly two decades later, specifying road widths in feet.

Bob Ladd said,

November 7, 2021 @ 10:55 am

More on topic: these collocations are readily borrowed within a broad cultural zone like "Europe". The expression "la route ouverte" certainly exists in French with essentially the same connotations as in English (rootless travel, etc. – the first hit on Google for the phrase is a song by Richard Seguin, whose lyrics are addressed to a vagabond friend), though of course it's difficult to be sure how many of the 19th century hits on the Google n-gram are for that meaning.

Chuck Pergiel said,

November 7, 2021 @ 1:07 pm

'French for "highwayman" is "voleur de grand chemin" = "big road thief".'

Does "big road thief" mean "big road-thief" (a big guy who steals roads) or "big-road thief" (a guy who steals big roads)? "Thief of the big road" might be better.

Richard Belaire said,

November 7, 2021 @ 7:56 pm

In Michigan most, if not all, secondary roads have property easements 60 ft wide, which would include pavement plus ditches.

Bloix said,

November 7, 2021 @ 8:09 pm

"Along with Kerouac’s notebooks, typescripts, and other documents, the Kerouac collection includes some books. In this case it is a copy of H. D. Thoreau’s “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers,” … But here’s what’s interesting, in the New Yorker’s words: “On page 227, this sentence—‘The traveler must be born again on the road’—was underlined in pencil, with a small, neat check mark beside it.”

http://richardhowe.com/2010/06/23/kerouac-on-thoreaus-road/

J.W. Brewer said,

November 7, 2021 @ 8:39 pm

In AmEng, at least by the time I came along, "on the road" has a specific idiomatic meaning having nothing to do with any specific identifiable highway, but rather the generic condition of touring musicians and other such vagabonds (by temperament or occupation) being in constant motion and ending up sleeping in a different town each night. When you are living like that,* the "road" you are on is somehow a generic one and any specific road you may have driven along on a particular day merges into a single generic The Road. myl may remember https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Road_Again_(Canned_Heat_song) from his undergraduate years. But what I don't know is whether that idiomatic usage predates Kerouac and thus influenced his title. It well may, but I don't have time this evening to try to google up lexicons of 1940's jazz-musician slang (or hobo slang etc). OTOH if it post-dates Kerouac, I suppose it's possible that the Kerouac title may have helped shape the idiom.

I would not expect a calque of that modern AmEng idiom into French or any other language to carry the same idiomatic meaning.

*Thus Townes van Zandt, no later than 1972:

"Living on the road, my friend,

Was gonna keep you free and clean.

And now you wear your skin like iron

And your breath's as hard as kerosene"

Bob Ladd said,

November 8, 2021 @ 4:32 am

@ J W Brewer: I think "the road" in the metaphorical sense is a somewhat separate question from the one MYL started with (namely, why specifically "open road"?), but I think it's fairly likely that that metaphor has been around in English since well before Kerouac wrote, or even before he was born. Obviously if you just do an n-gram on the phrase "on the road" you're going to get a lot of irrelevant hits, but if you do an n-gram on the four phrases "took to the road,life on the road,the open road,hit the road" they all suggest that the metaphor was already working by the second half of the 19th century. (I can't include a screen shot in this comment.)

As for calques in other languages, it seems pretty clear that this metaphor (involving the word route for 'road') is now found in French (see my comment above). The very successful French equivalent to the Lonely Planet travel guides, started in 1973, is called Le Guide du Routard. To judge from the Google n-gram, routard may be a coinage by the guide, adding the slightly-productive ending ard (as in clochard) to route.

However, I'm not aware of similar metaphors in other European languages. To return to the original question of "the open road", it seems that in Italian, if anything, the phrase "la strada aperta" suggests purposeful metaphorical travel, aiming towards a specific goal, etc. – essentially the opposite of the vagabond connotations of the English phrase.

Ed Rorie said,

November 8, 2021 @ 7:55 am

There are Front Streets in many U.S. towns.

KeithB said,

November 8, 2021 @ 9:02 am

"The Road", which Jackson Browne made famous in 1978, was written in 1972 by Danny O'Keefe:

https://americansongwriter.com/the-road-jackson-browne-behind-the-song/

Linda said,

November 8, 2021 @ 9:11 am

I just looked to see what the OED had on "open road" and it has an entry. . "A country road, or a main road outside the urban areas, where unimpeded driving is possible. In figurative contexts: freedom of movement."

And the citations go back to 1656 A. Cowley Muse ii, in Pindarique Odes 23 The Wheels of thy bold Coach pass quick and free; And all's an open Road to Thee.

Coby Lubliner said,

November 8, 2021 @ 11:50 am

It's interesting that the "royal" designation of main roads still persists in places in the Americas, for example Chemin du Roy and Avenue Royale in Quebec, and El Camino Real in California.

Coby Lubliner said,

November 8, 2021 @ 12:03 pm

@ Bob Ladd: The work cited, being a collection (recueil), may include some material written before 1799 (when the French foot was abolished). The pied royal, by the way, was slightly longer than the English foot: it was about 324.839 mm rather than 304.8 mm. (See French Wikipedia, Pied (unité)).

J.W. Brewer said,

November 8, 2021 @ 2:44 pm

@Coby L.: you don't even need a foreign language to semi-conceal "royal" toponyms, as witness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kings_Highway_(Brooklyn). There's another "King's Highway" in New Rochelle, N.Y., not far from where I live, which is part of the original pre-1776 route of the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King%27s_Highway_(Charleston_to_Boston) which deviates locally from the current alignment of U.S. 1.

Dara Connolly said,

November 8, 2021 @ 4:58 pm

Although we don't have High Streets in Irish towns (or where they exist, they are generally not the main shopping street), we have imported the terms "high-street fashion" and "high-street stores" to refer to the kind of shops that you might find on an English High Street.

Bloix said,

November 8, 2021 @ 10:19 pm

JW Brewer – the Thoreau quote in my comment above uses "on the road" in your sense. If it's too ambiguous for you, you could check out George M. Hayes, "Twenty Years on the Road, or The Trials and Tribulations of a Commercial Traveler" (1884).

Private Zydeco said,

November 9, 2021 @ 12:36 am

Almost Similarly Enough, but otherwise apropos of, well, nothing else really in se….

Some Interesting notes may be found on use of the (semi-antiquated) term "main" e.g. "Northern Main" ….

Certain theories trace its (hydro)geological meaning to the Spanish conquests in the Americas….

The trope seems to trip along from 'main-land' to 'mainstay' into 'main-line'….

https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/224035/etymology-main-meaning-sea-or-ocean

https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-etymology-of-main-meaning-sea-or-ocean

J.W. Brewer said,

November 9, 2021 @ 11:23 am

Going back to "grands chemins royaux," the idiom "royal road" meaning "easy/foolproof method of learning something" was already established in English by the early 19th century (and perhaps earlier than that). While it seems to have arisen from a classical tale in which some ancient big-shot was advised that there was "no royal road" (i.e. no low-effort short cut) to learning Euclidian geometry, it got turned around and used to market purported sure-thing short-cuts, as witness e.g. book titles like "The Universal Ready Reckoner, or Royal Road to Arithmetic; being instructions in the use of the Sliding-Rule: compiled for the use of Ladies and idle Gentlemen." You could also purchase "Method Against Memory; or a Royal Road to Short Hand" (published 1832), complete with an old-timey servile dedication to the Rt. Hon. Earl of Munster &c. &c. &c.

Philip Taylor said,

November 9, 2021 @ 2:07 pm

Smoewhat amused by the implied similarity between ladies and idle gentlemen, I asked Google Ngrams about the frequency of usage of that phrase. Since 1993, only one author appears to have used the phrase spontaneously, but in the period 1852–1992 it was by no means uncommon, with the word "ladies" often being preceded by an appropriate adjective : "perfumed", "fashionable", "fine", "wealthy", …

Bloix said,

November 10, 2021 @ 8:39 pm

The actual Royal Road was built by the Persian king Darius the Great across his empire, and was marveled over by Herodotus. (We remember Darius for his defeat at the battle of Marathon and forget that he conquered Thrace, Macedonia, and Egypt in the West and expanded his empire along the Black Sea and in the East as well.) At least one bridge built for the Royal Road still stands.

The metaphorical use is attributed to Euclid, who supposed told Ptolemy that "there is no Royal Road to geometry."

Francis Boyle said,

November 12, 2021 @ 5:51 am

Linda's quotation from 1656 suggests to me one answer to Mark's question. Plausibly, the wheels of the coach "pass quick and free" due to the absence of toll barriers. So the open road is in a very mundane sense "the free road".

Philip Taylor said,

November 12, 2021 @ 9:25 am

To be honest, Francis, I am not convinced. For me, the "free" in "quick and free" refers to a lack of physical obstacles — rocks, boulders, fallen trees, deep gullies, precipitous drops, clinging mud, etc. As the Fossils might say, "'free' as in 'libre', not as in 'beer'.