Vocabulary of Hong Kong protest slogans and new characters

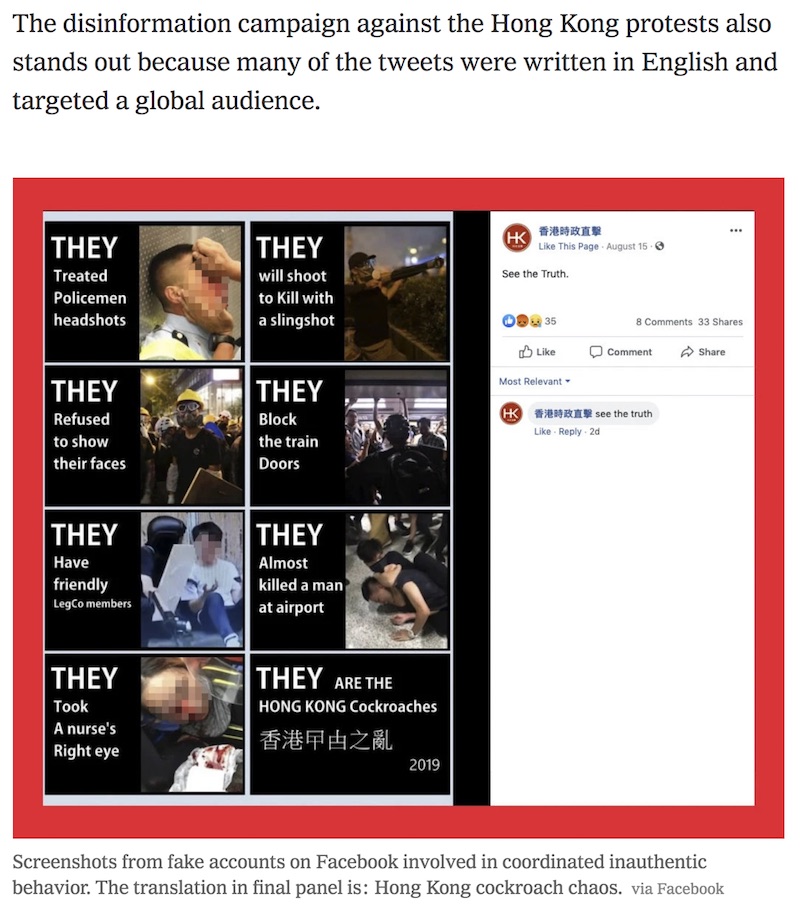

The Hong Kong extradition bill protesters have developed a vocabulary of slogans and newly invented polysyllabic characters which they wield deftly. Here are two instances from the Twitter feed of Ryan Ho Kilpatrick documenting this weekend's protest activities on the way to and in the Hong Kong International Airport. If you scan through the photographs and short videos from the top to the bottom (there are some pretty rough, raw scenes), you can get a sense of the tension that continues to build after 11 weeks of protests that have convulsed Hong Kong, at times with hundreds of thousands or even millions of people on the street expressing their firm opposition to the heavy-handed policies of the Beijing government.

This calligraphy though. pic.twitter.com/eiA9uXFymQ

— Ryan Ho Kilpatrick 何松濤 @ryanhk.bsky.social (@rhokilpatrick) September 1, 2019

Read the rest of this entry »