Archive for Historical linguistics

April 23, 2019 @ 10:16 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Historical linguistics, Numbers, Reconstructions

Serious problem here.

Clauson, An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-Century Turkish, p. 507b:

F tümen properly ‘ten thousand’, but often used for ‘an indefinitely large number’; immediately borrowed from Tokharian, where the forms are A tmān; B tmane, tumane, but Prof. Pulleyblank has told me orally that he thinks this word may have been borrowed in its turn fr. a Proto-Chinese form *tman, or the like, of wan ‘ten thousand’ (Giles 12,486).

Source (pdf)

[VHM: the "F" at the beginning of the entry means "Foreign loanword"]

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 21, 2019 @ 7:01 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Historical linguistics, Language and archeology, Language and biology, Language and culture, Language and history, Phonetics and phonology, Reconstructions

This post was prompted by the following comment to "The emergence of Germanic" (2/27/19):

…while riding horses _in battle_ is post-Bronze Age (and perhaps of questionable worth at any time), I think riding in general is older, and probably (assuming the usual dating of PIE) common Indo-European.

The domesticated horse, the chariot, and the wheel came to East Asia from the west, and so did horse riding:

Mair, Victor H. “The Horse in Late Prehistoric China: Wresting Culture and Control from the ‘Barbarians.’” In Marsha Levine, Colin Renfrew, and Katie Boyle, ed. Prehistoric steppe adaptation and the horse, McDonald Institute Monographs. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2003, pp. 163-187.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

April 2, 2019 @ 2:43 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Classification, Grammar, Historical linguistics, Language and history

[This is a guest post by Douglas Q. Adams]

For over a hundred years now linguists have known of a small Indo-European family comprised of two closely related languages, Tocharian A and Tocharian B, in the Tarim Basin of eastern Central Asia (Chinese Xinjiang). Tocharian B speakers occupied the northern edge of the Tarim Basin, north of the Tarim River, from its origin at the confluence of the Kashgar and Yarkand rivers eastward to about the halfway point to the Tarim’s disappearance into Lop Nor. Politically Tocharian B speakers were certainly the major constituent of the population of the kingdom of Kucha and natively they called the language (in its English form) Kuchean. To the east-north-east, in the Karashahr Basin, were speakers of Tocharian A, centered around Yanqi (Uighur Karashahr, Sanskrit Agni). On the basis of the Sanskrit name this language is sometimes referred to as Agnean, though we do not have any direct or conclusive evidence as to what the speakers themselves called it. To the east-south-east of Kuqa, along the lower Tarim was the historic kingdom of Kroraina (Chinese Loulan < Han Chinese *glu-glân). The administrative language of Loulan was Gandhari Prakrit, obviously imported into the Tarim Basin along with Buddhism from northwestern India. In documents of the Loulan variety of Gandhari Prakrit are non-Gandhari words that have been attributed to the native language of the area. Some of those non-Gandhari words look like Tocharian (e.g., kilme ‘region’ beside TchB kälymiye ‘direction’) and it has seemed a reasonable hypothesis that the native language of Kroraina/Loulan was another Tocharian language, “Tocharian C.” (That the native language of Loulan was Tocharian was first suggested by Thomas Burrow in his The Language of the Kharoṣṭhī Documents from Chinese Turkestan, 1937.) This is a reasonable hypothesis, for which the evidence is admittedly meager, and many have been (reasonably) dubious or unconvinced.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

March 8, 2019 @ 9:39 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Historical linguistics, Language and music, Phonetics and phonology, Pronunciation

This morning while shaving, as I was listening to the radio around 7:30 a.m., I heard a medley of songs by three artists, all with the same title: "Hold on". But a funny thing happened in all three of these renditions: whenever the singer pronounced the title phrase, it always came out as "hol don", at least to my ear. But I don't think it was just my ear, since several times they prolonged the "hol" syllable and emphasized the "d" at the beginning of the "don" syllable.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 27, 2019 @ 8:58 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Historical linguistics, Language contact

From their origins to the present day, speakers of Germanic languages have been distinguished by the high degree of their mobility on land and on water: the Völkerwanderung during the Migration Period, Goths, Vikings, the British Empire on which the sun never set, Pax Americana…. From antiquity, they ranged far and wide, so it is not surprising to see them popping up all over the place and, in their travels, to come in contact with an enormous number of different ethnic and linguistic groups.

Before setting out on their multitudinous journeys, they had to have begun somewhere, and — on the borders of their original homeland — they had to have been in contact with other ethnic and linguistic groups. I asked a colleague where and when they might have arisen, and who their neighbors were.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 20, 2019 @ 11:13 am· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Words words words

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

New URL for COFEA and COEME: https://lawcorpus.byu.edu.

This post on what arms means will follow the pattern of my post on bear. I’ll start by reviewing what the Supreme Court said about the topic in District of Columbia v. Heller. I’ll then turn to the Oxford English Dictionary for a look at how arms was used over the history of English up through the end of the 18th century, when the Second Amendment was proposed and ratified.. And finally, I’ll discuss the corpus data.

Justice Scalia’s majority opinion had this to say about what arms meant:

The 18th-century meaning [of arms] is no different from the meaning today. The 1773 edition of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary defined ‘‘arms’’ as ‘‘[w]eapons of offence, or armour of defence.’’ Timothy Cunningham’s important 1771 legal dictionary defined ‘‘arms’’ as ‘‘any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another.’’ [citations omitted]

As was true of what Scalia said about the meaning of bear, this summary was basically correct as far as it went, but was also a major oversimplification.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

February 15, 2019 @ 7:57 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Historical linguistics, Phonetics and phonology

[This is a guest post by Chris Button]

There are a couple of brief suggestions in Mallory & Adams' Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997:314;379) that the Lithuanian word geležis and Old Church Slavonic word želežo for "iron", which following Derksen (2008:555) may be derived from Balto-Slavic *geleź-/*gelēź- (ź being the IPA palatal sibilant ʑ), could possibly have a Proto-Sino-Tibetan association.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 29, 2019 @ 8:03 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Research tools, Words words words

From the Washington Post:

The study is a corpus analysis performed by Jesse Egbert, a corpus linguist at Northern Arizona University and Clark Cunningham, a law professor who did work in law and linguistics from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s (link, link, link, link), including co-authoring an article with Chuck Fillmore that was what really opened my eyes to the power of linguistics in analyzing issues of word meaning.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

January 25, 2019 @ 6:52 pm· Filed by Victor Mair under Historical linguistics, Language and history, Transcription, Translation

[This is a guest post by Chau Wu]

There is a long-standing puzzle that has attracted historical linguists’ interest. This is a single sentence of 10 characters in two clauses: “秀支替戾岡, 僕谷劬禿當” (xiù zhī tì lì gāng, pú gŭ qú tū dāng). The sentence does not make sense in any of the Sinitic topolects. Obviously, this appears to be from a foreign language using Sinographs as phonetic transcriptions. Indeed, the source document which gives this mysterious sentence clearly indicates this is in Jié 羯, a non-Sinitic language that showed up in China during the chaotic period known as the Sixteen Kingdoms (304-439 CE) marked by uprisings of 五胡 wŭhú ‘Five Barbarians’ (Xiōngnú 匈奴, Jié 羯, Xiānbēi 鮮卑, Dī 氐, and Qiāng 羌) against the Jìn 晉 dynasty.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

December 16, 2018 @ 3:30 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Dictionaries, Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography, Words words words

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

New URL for COFEA and COEME: https://lawcorpus.byu.edu.

Starting with this post, I’m (finally) getting to the meat of what I’ve called “the coming corpus-based reexamination of the Second Amendment.” The plan, as I’ve said before, is to more or less mirror the structure of the Supreme Court’s analysis of keep and bear arms. This post will focus on bear, and subsequent posts will focus separately on arms, bear arms, and keep and bear arms; I won’t be separately discussing keep arms because I have nothing to say about it. [Update: If you're confused about why I'm following this approach, as one of the commenters was, I've offered an explanation at the end of the post.]

In discussing the meaning of the verb bear, Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller said, “At the time of the founding, as now, to ‘bear’ meant to ‘carry.’’’ That statement was backed up by citations to distinguished lexicographic authority—Samuel Johnson, Noah Webster, Thomas Sheridan, and the OED—but evidence that was not readily available when Heller was decided shows that Scalia’s statement was very much an oversimplification. Although bear was sometimes used in the way that Scalia described, it was not synonymous with carry and its overall pattern of use was quite different.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

December 16, 2018 @ 8:40 am· Filed by Victor Mair under Borrowing, Historical linguistics, Language and archeology, Language and culture, Phonetics and phonology, Reconstructions

[The first page of this post is a guest contribution by Chris Button.]

I've been thinking a little about the word represented by chái 豺* which I would normally reconstruct as *dzrəɣ (Zhengzhang *zrɯ) ignoring any type a/b distinctions. However, it occurred to me that a reconstruction of *dzrəl (for which Zhengzhang would presumably have *zrɯl) would give the same Middle Chinese reflex (I'm not citing Baxter/Sagart since they don't support lateral codas presumably for reasons of symmetry). I'm not sure if outside of its phonetic speller cái 才 there is any reason to go with -ɣ rather than -l in coda position for 豺. However, if we go with a lateral coda as *dzrəl, it looks suspiciously similar to Old Iranian šagāl from Sanskrit śṛgāla (perhaps even more so if we fricativize the Old Iranian /g/ to /ɣ/ intervocalically as in modern Persian).

[*VHM: This is always a challenging word for translators. "jackal" and "dhole" are two possibilities.]

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

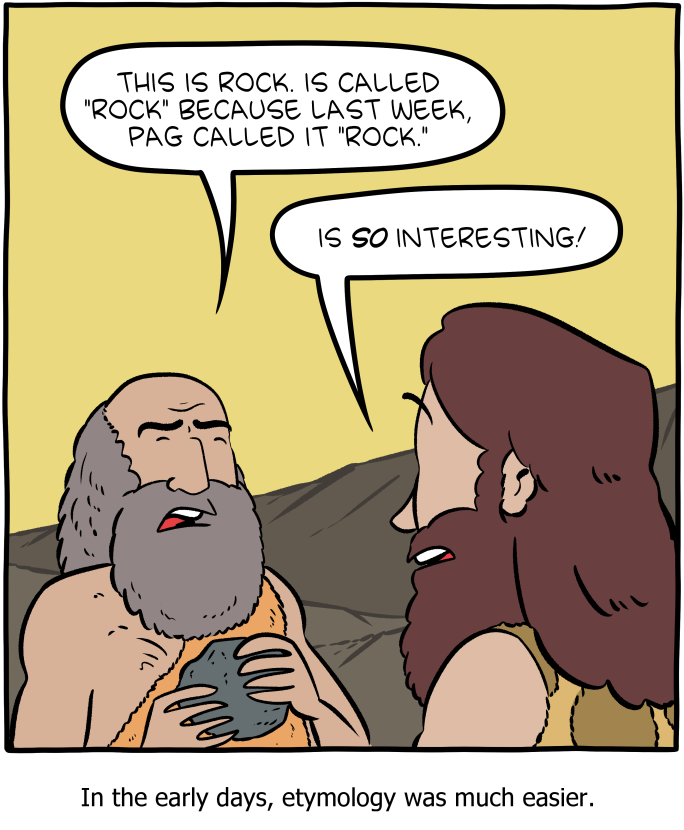

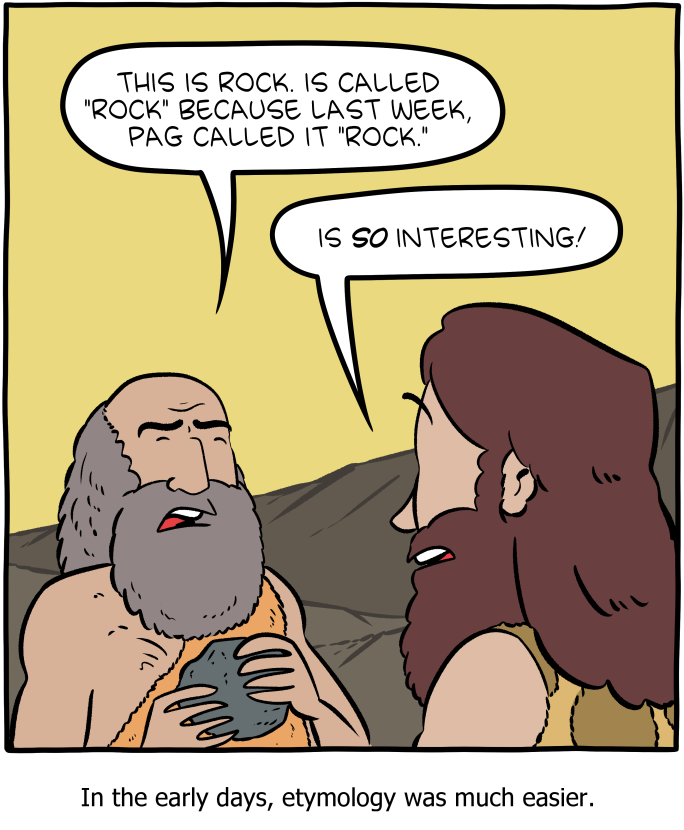

November 9, 2018 @ 11:22 am· Filed by Mark Liberman under Etymology, Historical linguistics

Yesterday's SMBC:

Mouseover title: "Chicken etymology is really easy because the word origins AND the words you use to describe them are all 'bock bock bock'."

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink

August 9, 2018 @ 1:28 pm· Filed by Neal Goldfarb under Etymology, Historical linguistics, Language and the law, Lexicon and lexicography

An introduction and guide to my series of posts "Corpora and the Second Amendment" is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the "Download" button at the top right of the screen.

With this post, I begin my examination of the corpus data regarding the phrase keep and bear arms. My plan is to start at the level of the individual words, keep, bear, and arms, then proceed to the simple verb phrases keep arms and bear arms, and finally deal with the whole phrase keep and bear arms. I start in this post and the next one with keep.

As you may recall from my last post about the Second Amendment, Justice Scalia's majority opinion in D.C. v. Heller had this to say about the meaning of keep: "[Samuel] Johnson defined 'keep' as, most relevantly, '[t]o retain; not to lose,' and '[t]o have in custody.' Webster defined it as '[t]o hold; to retain in one's power or possession.'" While those definitions could be improved on, I think that for purposes of this discussion, they adequately explain what keep means when it's used in the phrase keep arms. So I'm not going to discuss that data with an eye to criticizing this portion of the Heller opinion.

Instead, I'm going to use the data for keep as the raw material for an introduction to the nuts and bolts of corpus analysis. I suspect that many people reading this won't have had any first-hand experience working with corpus data, or even any exposure to it. Hopefully this quick introduction will enable those people to better understand what I'm talking about when I start to deal with the data that does raise questions about the Supreme Court's analysis.

Read the rest of this entry »

Permalink